Why would canon lawyers support “preferred pronouns”?

Far from condemning "preferred pronouns," the Holy See's highest court created space for them in 1975.

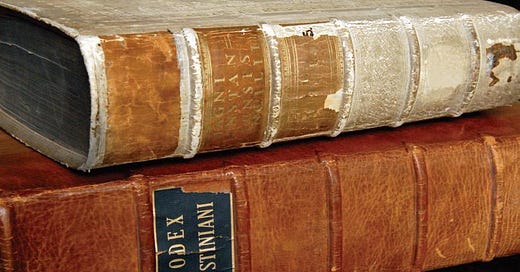

The Roman Rota is like the Supreme Court for the Catholic Church. Local diocesan tribunals typically manage canon law cases on matters ranging from annulments to clerical discipline, and the decisions from diocesan tribunals can then go through appeals processes, where the Roman Rota is the court of last resort.

I was first made of the 1975 annulment case between R and M by a canon lawyer friend a few years ago. (It’s interesting to note that this decision came down during the papacy of Pope Paul VI.) The case considers whether the couple’s marriage can be annulled after they have separated and R has openly come out as a “transsexual.” It looks at two questions: first, whether R could have really consented to marriage and its obligations and, second, whether there was sufficient “error” in M’s understanding of who she was marrying.

Definitions

The Rota decision provides some helpful definitions to its now-outdated terms. It defines transvestism as “(the) psychosexual phenomenon in which the subject… plays the role of the opposite sex by being conscious of belonging to a specific sex. In this dimension the subject searches for sexual identification in the clothing and in the assumption of tastes, practices, and behavior patters of the opposite sex.” It defines transsexualism as “a psychosexual syndrome characterized by the tested feelings of an individual of a specific sex… of belonging to the opposite sex. Such a feeling is accompanied by the desire to change one’s own somatosexual configuration with surgical or hormonal treatment.” (The case also uses an older and no longer relevant treatment of “homosexuality,” which I will not go into here.) In other words, a “transvestite” man is someone who will dress up or play the “role” of a woman for various reasons, even while seeing himself deep-down as still a man. And a “transsexual” is someone who may be biologically male but believes themselves, deep down, to really be a woman, and who may (or may not) respond to this deep-seated feeling through hormonal or surgical treatments.

The Rota notes that at the time of the decision there had been no clear biological etiology for either and that “‘up to now all attempts at a cure’ [for transsexualism]… have failed.” It also says draws on research stating that many transsexual patients “do not have any wish to ‘remedy’ their state” and that for them, the transsexualism “corresponds to their true ego; instead, they have desired to be liberated from their loathed male attributes. Every attempt to strengthen their masculinity has appeared as an attack on the laws of nature.'”

The Rota notes various types of male-at-birth “transsexuals,” (a) some where they take estrogen but do not desire surgical interventions, (b) others who desire surgery but cannot obtain it and seek a balance through surgery and estrogen, and (c) others who so urgently seek surgery that they will turn to self-mutilation or suicide if it is denied to them. So while some “transsexuals” will want hormones or surgery, others will not.

The Rota, most likely because it does not have a body of knowledge on the question of “transsexualism,” examines how “hermaphroditism” has been treated in its legal tradition. Previously, a hermaphrodite’s sex was considered “that which is predominant in the person.” In the event that both sets of genitals for a hermaphroditic person were functioning (as was previously believed possible), a hermaphroditic person could canonically marry as either a man or a woman. Changing this after the choice would be “gravely illicit” but would not invalidate subsequent marriages. This is interesting, as it assumes the possibility that would could validly (even if not licitly) move between one gender and another for the purposes of marriage.

“Psychological Sex“

But the Rota says that “transsexualism” is different from “hermaphroditism,” because “transsexualism” involves not a genital question but a dissociation between “psychological sex” and “genetic, gonodal, hormonal and somatic sex.” Surprisingly to readers today, the Rota says:

“Nothing prevents predominance from being attributed to psychological sex as regards those matters which do not exceed the juridical capacity of the subject. For the canonical teaching which, in cases of doubtful sexuality, recognized the right for the subject to make a definitive choice of sex, can be applied ‘when there is a question of ordering one’s purely external and social life, e.g., of wearing men’s or women’s clothing, of giving testimony in instruments, of the right to determine an heir.'”

In other words, canon law does not prohibit the treatment of psychological sex as primary for “transsexual” persons when it comes to how they order their life generally. This includes how they dress, present, and identify themselves.

That being said, the Rota argues that this question of sexual predominance is not determinative for the purposes of determining whether R was able to consent to the marriage with M. The Rota argues that a marriage can be valid, even “if contracted according to the non-predominant sex provided there is potency for perfect copula.” In other words, though the Rota recognizes the possibility that R’s “predominant sex” may not have been male, R was able to consent to marriage as a male as long as she (here using “she,” assuming that this is the “predominant sex and was how R identified later in her “external and social life”) could complete the sexual act with M. The Rota draws on contemporary research arguing that “transsexuals,” though they may have “psychological disturbances” associated with what we not call gender dysphoria, such “disturbances” are “not accompanied by perturbations in the intellectual and volitional sphere.” So gender dysmorphia does not necessarily mean that a person is mentally incapacitated or unable to make decisions such as whether to marry.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that this case arose before the 1983 Code of Canon Law, with its changed definition of “consent.” The 1917 Code defined marital consent as “an act of the will by which each party gives and accepts perpetual and exclusive rights of the body, for those actions that are of themselves suitable for the generation of children. The 1983 Code changed the definition of matrimonial consent to “anact of the will by which a man and woman mutually give and accept each other through an irrevocable covenant in order to establish a marriage.” Since the 1975 Rota decision, the Code of Canon Law has moved away from its focus on the body in marital consent and has moved towards a focus on the couple generally. The change reflects an overall shift in the focus of Catholic marriage from one oriented around and towards the sexual act and its effects, to one oriented around what some have called a more “personalist vision” of the couple.

What This Tells Us

There are a few interesting things to note about the 1975 case. Though the marriage was ultimately found valid at the time it was contracted, the Rota did not discount R’s claims. It found in its decision that R was a “transexual” based on R’s testimony, even though R’s wife and family denied this. Its decision proceeded on the assumption that psychological and biological sex could differ, and that psychological sex could be a person’s “predominant sex.” And, finally, it created space for “transsexuals” to present themselves as and identify with their “psychological sex.” Far from condemning “preferred pronouns,” the Holy See’s highest court created space for them in 1975.

This does not provide a final say on pastoral, social, moral, theological and canonical questions related to trans persons. It’s also important to note that our understanding of “trans persons” today is different from that of “transsexuals” in 1975. But the case does indicate that if we want to draw on what little the “Catholic tradition” has provided thus far with regards to these specific questions, that tradition does not give us answers that fall neatly into many of our expectations. It’s worth noting that Boleslaw Filipiak, Dean of the Roman Rota at the time of the decision, was elevated to his position in 1967 by Pope Paul VI and then further elevated to Cardinal in 1976. A Pole who received his canon law degree from the Institute Utriusque Iuris, it’s highly unlikely Cardinal Filipiak was what we would today call a “liberal.”

All of this may be why the canon lawyers I know don’t jump to easy conclusions with regards to the “gender identity” of trans persons. They tend to be deferential to the person with the experiences. They opine, but they do not dictate. These matters are much more complicated than many assume them to be.

For further discussions of the 1975 case, I’d recommend this piece by James Heaney, which you should read. (You should actually just read all his stuff.) You can also see this discussion by Jennifer Haselberger.