Newsletter #5: rewriting history

Revisionist history, Zoom accessibility, rereading the Gospels, and more!

Happy Tuesday! I’m visiting South Bend for the next couple of weeks. It’s been weird spending time on my old college campus. I’ve had to process a significant amount of trauma from my college days, but I feel good about the direction of that processing.

Shortly after I graduated, I hated the Notre Dame. Most of my traumatic sophomore year was a blank space in my memory. And returning to campus filled me with anxiety, fear, and anger. Because of my difficult time there, I had a narrative of my college history: Notre Dame was a place that rejected and wounded me. I wanted to just put it behind me. But I’ve learned that my hurt and anger, if avoided, don’t disappear; they just get stored away in some part of myself and reemerge from time to time. Choosing to emotionally engage with those hard parts of my history has allowed me to handle and transform my hurt, my anger, and my relationship to my past. It’s also created space for other emotions. A lot of good memories from college have come back. I’m happy to have them again.

It makes me think of one of my favorite scenes from The Good Wife. The show starts out with a housewife discovering her husband, a Chicago attorney and politician, had been cheating on her with prostitutes. Over the course of the show, the wife becomes a powerful attorney herself who navigates a complicated relationship with her husband. In one of the later seasons, the two have become friends again and are processing her past anger. The husband tells her, "I was never as bad as you wanted me to be." She acknowledges that this may be true. The acknowledgement provides some closure and healing for both of them. While still recognizing the pain, they can both recognize that things aren’t always as simple as our hurt and anger want them to be.

For me, Notre Dame isn’t “a good place” or “a bad place.” It’s a complicated place with which I have a complicated relationship, and that’s okay. I hate some of the things I went through at Notre Dame. But I also recognize that there is much good in my past there, and there are opportunities for the University (and me) to do good in the future. Working through a revisionist history (more on this below) of my time at Notre Dame can help all of us move forward.

Here’s what’s in the newsletter today:

What is revisionist history?

Zoom accessibility

Creating space for LGBTQ+ love and desire

Ruden’s Gospels on how power goes to the unclean

What is “revisionist history”?

Right now the United States is going through history wars. On the one hand, Republicans in southern states are being accused of trying to rewrite history to hide past racial injustices through legislation and curriculum. On the other hand, the 1619 Project and critical race theory are accused of rewriting history through the lens of “wokeness.”

To be sure, critical race theorists and many others are invested in “historical revisionism.” But this “revisionism” often isn’t so much about “remaking” history to fit an ideology, as it is about bringing to the light parts of history that have been ignored because marginalized and oppressed voices have been ignored. Mari Matsuda, one critical race theorist, believes that legal methodology grounded in the social reality and experience of people of color is “consciously historical and revisionist” because “[u]nderstanding history from the bottom has forced these scholars to sources often ignored: journals, poems, the records of practitioners, the rhetoric of intellectuals of color, oral histories, the writers’ own experience of life in a hierarchically arranged world, and even to the dreams they dream at night in their sleep.” For Matsuda, revisionist history is history that takes into account what has often been ignored in the dominant histories told today.

Charles Lawrence, another critical race theorist, expands upon this:

“Historical revisionism is critical because full personhood is itself defined in part by one’s authority to tell one’s own story. Historians make history even as they record it. Discovering and rewriting the record reshapes history itself, and our contemporary social context is in turn changed.”

Critical race theorists might be viewed as historical revisionists, in the way that Galileo might be viewed as a scientific revisionist. They help illuminate what has been hidden, and when they do this, they help us grasp a fuller vision of reality.

Zoom Accessibility

I recently attended a training with a “virtual presence coach” who talked us through how to present well in virtual meetings. In her presentation, she shared that a bold lipstick color (for people who wear lipstick) can make meetings more accessible, by making it easier for people who need to lipread.

Apparently, there are a number of things we can do in our Zoom calls and presentations to make them more accessible and a better experience for others. A couple other tips that can make your zoom presence more other-centered:

People feel more anxious when they see doors and hallways in your background because they’re watching for someone to open or walk through them. Angle your camera away from them to avoid unnecessary distractions.

Minimize motion by removing things like fans, flags, and fluttering curtains from your background. This increases accessibility for people who have attention deficit disorder, motion sickness, dyslexia, epilepsy, or migraines.

People need to smile more in Zoom meetings than in physical meetings in order to better humanize the interaction. So make sure you over-smile.

If you see yourself on the call, you’re more likely to get distracted looking at yourself and increase your own anxiety. Use the “hide self view” option in Zoom to stay focused on others.

Creating space for LGBTQ+ love and desire

Last week, I wrote about hedonism, asceticism, and the transformation of desire. Among other things, I argued that Catholics need to reframe asceticism as a concept and a practice, focusing on creating space for love and messiness in the context of sexual development. One way of reading my argument was as a sort of defense of gay sex, in the context of developing one’s sexuality in a way that is more relational and other-centered. Ultimately, however, it is an argument about the need for gay Christians to be gracious with ourselves as we navigate love and desire in the Church. too often, we get gaslighted into making the same mistakes over and over. MacIntyre, Coakley, Pope Benedict XVI, Bonaventure, and others can help us imagine away out of these vicious cycles. You can read more here.

What I’m Reading: Power goes to the unclean: Sarah Ruden translates the Gospels

I’ve started making my way through Sarah Ruden’s translation of The Gospels. I first became aware of Ruden’s work through her book Paul Among the People. In that book, Ruden uses her skills as a classicist to show the reader how Paul may be receiving unfair treatment from contemporary critics. Rather than subjugating women, for example, Ruden argues that Paul provides the basis for a liberation of women in a society that has systemically excluded, marginalized, and silenced them. Ruden draws on her knowledge as a scholar of antiquity and a translator of Greek texts to explore the message of freedom and love that she sees obscured by the ways we tend to read Paul today.

In an even more ambitious work, Ruden seeks to give a fresh and unusual take on the Gospels through her new translation. As a Quaker, a “member of perhaps the least theological, most practical religious movement in the world” (as she puts it), Ruden wants a translation of the Gospels that is straightforward, that helps “people to respond to the books on their own terms.” She writes, “[N]ever before, in nearly forty years of translating, have I found texts so resistant to this purpose.” This is her aim.

So her translation will, at times, come off as bizarre to many readers. She’s not concerned with ecclesial posture or theological content. (For this, Thomas More might have burned her.) Instead, she translates the text in a way that she might translate other texts from that time period. One unusual choice is her use of Hellenic names. Jesus is “Iesous,” Peter is “Petros,” John is “Ioannes,” and so on. Indeed, even “Gospel” becomes what we often forget it is: “the Good News.”

I love reading new translations of ancient texts. I’ve found that they can bring to light what is often hidden within the original language. There’s something imminent and worldly in the words from Isaiah quoted at the beginning of “The Good News According to Markos.” Ruden translates the passage as: “‘Look, I’m sending my messenger ahead of you, / And he will build your road.’” That passage is often translated to end with “who will prepare your way.” The idea of a “road” being “built” gives us the feeling of an imminent, tangible journey, as opposed to a “way” which one is tempted to treat esoterically.

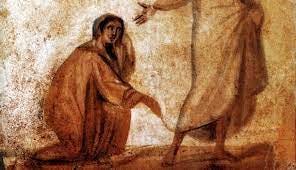

Ruden’s mode of translation is striking on every page. In Markos 5, she tells the story of the bleeding woman:

“Now there was a woman who’d been afflicted with a flow of blood for twelve years. She’d suffered greatly at the hands of many doctors and spent everything she had, but found no relief—instead, she’d gotten worse. When she heard about Iesous, she came up behind him in the crowd and touched his cloak, telling herself, ‘If I just touch his clothes, I’ll be cured.’ And right away, the spring of her blood dried up, and she sensed in her body that she had been healed of her scourge. But right away Iesous clearly sensed in himself that power was going out of him, and he turned around in the crowd and said, ‘Who touched my clothes?’ … [H]e went on looking around to see which female had done this thing. But the woman, terrified and shaking, and knowing what had happened to her, came and threw herself at his feet and told him the whole truth. But he said to her, ‘Daughter, your trust has cured you. Be on your way in peace and be healthy after your scourge.’”

One strength of this translation is that it resists attempts to over-theologize the woman’s situation. It speaks in a language approachable to poor, exhausted, chronically ill persons, with short phrasing and and word choices focusing on physicality. It’s easy to imagine someone today in the woman’s situation saying, “If I just touch his clothes, I’ll be cured.” Other translations give this woman a very different sort of voice. The New American Bible translates this as, “If I but touch his clothes, I shall be cured.” When I read the NAB translation, I’m tempted to think of a pretty young girl with a British accent, someone who probably read a lot of Jane Austen, someone I’d never meet sitting against a building in downtown Minneapolis. The voice Ruden gives to the woman actually sounds like someone in her situation. She sounds like my poor clients when I practiced social security disability law.

And notice the physicality of the word “scourge” (μάστιγός) at the end of the passage, in contrast to the more vague choice of “suffering” in the New International Version. The word “scourge” offers more to the reader in its specificity, and it draws more on the Greek word μάστιξ, which can also be translated as “whip” or “plague.” “Scourge” also ties the woman to Jesus, who himself is whipped/flogged (φραγελλώσας) in other Gospel accounts. For all its practicality, Ruden’s work offers us depth in areas not found in other translations.

I also love Ruden’s footnotes. With this story, Ruden includes in a note, “[T]his woman is presumably Jewish, and thus bound by the purity laws that would render her untouchable as long as she experiences the uncleanliness of a discharge.” What this commentary reveals to us is that the unclean receive a portion of the power of God when they go to touch Him. It is precisely the trust required for the unclean untouchable social outcast to go touch Jesus which draws out the power of God.

Indeed, her touching him is astonishing itself. When the story is retold in “The Good News According to Matthaios” (9:20-22), the woman touches the κράσπεδον (kraspedon), the “hem “ or “edge” of Iesous’s garment. Ruden comments that this “could be the tassels Israelite men are commanded to wear, to remind them of the law.” But Ruden also notes that the woman “is breaking the law by her physical contact while she has a discharge.” So not only is the woman drawing out the power of God in her uncleanliness, but, even further, it is her double-breaking of the law which causes this to occur. Ruden’s commentary suggests that it is possible that her unlawful touching of the reminder of the law which draws out the power of God and heals her.

You should read Ruden’s new translation. It’s a helpful reminder that the Good News is a very odd thing, and it always has something new to offer us.

You can follow along with my current reads at Goodreads.

Now accepting submissions!

If you like what I’m doing here and want to join in this developing project, I’d love for you to submit an essay, poems, or a short story for consideration. You can learn more here.

Follow Along

And that’s all I have for you today. If you’re on social media, you’re welcome to also follow me at Twitter and on my Facebook page. Stay tuned for next week’s essay on misuses of religious liberty, Catholic Social Teaching’s approach to the State, and the limits of civil disobedience.