When the Liberals Come for the Church, and Changing Fears of Violence

Over the years, I've found a shift in my concerns for safety.

During the Obama presidency, I remained convinced that secular liberals were seeking to destroy the Church. I thought their liberal agenda would eventually turn illiberal. Bishop Daniel Jenky of Peoria was warning that Obama’s policies against religious freedom had placed him on a path similar to Hitler’s. He preached:

“Hitler and Stalin, at their better moments, would just barely tolerate some churches remaining open, but would not tolerate any competition with the state in education, social services, and health care. In clear violation of our First Amendment rights, Barack Obama – with his radical, pro abortion and extreme secularist agenda – now seems intent on following a similar path.”

Bishop Jenky later clarified by stating he didn’t want to make a direct comparison, but that “our country is starting down a dangerous path that we’ve seen before in history.”

I raised similar concerns at the time, quoting in a campus newspaper a remark I had heard from a Notre Dame professor:

“I have many friends here [at Notre Dame], but I also have many enemies. … If they could get police to come to my door and hold a gun to my head until I paid for their birth control, they would. These are your enemies.”

The professor and I both held views that conflicted with certain Obama administration priorities, and we objected to paying for them. We worried about the amount of coercion many liberals wanted the administration to exercise, from shutting down religious foster services that objected to same-sex marriage to forcing Catholic schools to fund contraceptives which could act as abortifacients.

There was a certain fury surrounding religious institutions which objected to core progressive commitments. We, religious conservatives, worried progressives would rather have us jobless, institutionless, and even dead, than tolerate our refusal to engage in and pay for goods and services we deemed harmful and immoral. We worried for our safety, and of the possibility of eventually being jailed or ostracized because of our sincerely held religious views. I thought that Catholicism was the religion of truth, while secular liberalism would eventually be unveiled as a religion of violence and coercion.

Even if hyperbolic, my concerns for safety as an open religious conservative weren’t entirely unjustified. I realized this when I had to deal with a stalker in the middle of law school. This was the first time that I felt openness about my views could result in physical danger.

The Stalker

He was an older man, a gay attorney from the south, who had read my conservative views on sexuality and marriage. He objected to them and wanted me to take time to listen to his frustration with my writing. It started with comments on my blog. Then he started emailing me. After realizing that he wanted to be belligerent and confrontational, I stopped responding to him. Then he called my law school, inquiring how he could contact me.

This was a line crossed which scared me. Because the man was an attorney, I consulted with a legal ethics professional about what I could do. I had to explain the situation to some of the law school staff. I coordinated a response in which I told him through a third party that I would contact his state bar association if he continued to contact me, and that I did not consent to further contact from him. I changed my name on all my social media accounts, and I fell asleep at night wondering whether I would wake up to a strange man banging on my front door, trying to attack me.

The secular left has its fair share of unbalanced advocates and belligerent apologists. I received my fair share of hate mail in the days when I was publicly defending and promoting the Catholic Church’s position on sex and sexuality. But my fears about the Obama administration and its advocates never came true. No person in a real position of authority or liberal leadership in America has sought the criminalization of my views. I never heard of anyone in my liberal legal community advocating that persons who shared my views ought to be imprisoned or harmed.

In the years between my work as a traditional Catholic apologist and today, the world has changed significantly. It’s easy to forget that Obama once opposed same-sex marriage, or that in much of the US it was once unusual to even know someone who was gay. Before I came out, most of my friends thought it was inconceivable to have a gay man who was also a committed Catholic. But here I am. And here is same-sex marriage, the law of the land in the United States.

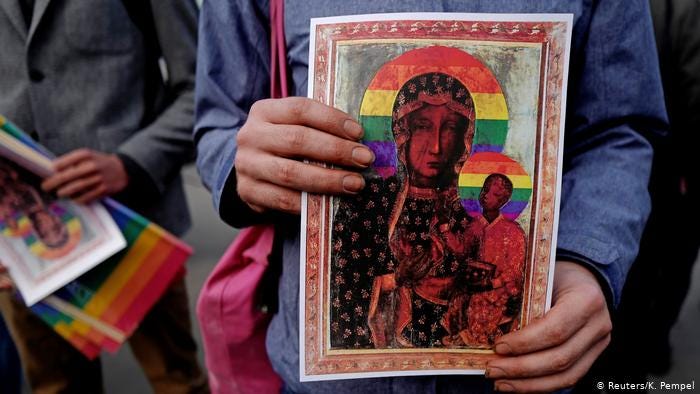

Much has changed in the United States, and across the world. But many still struggle with the intersections between religion and homosexuality, between Christianity and gay persons. One way in which this intersection has resulted in conflict has been the use of the “Rainbow Madonna,” a remaking of the image of the Black Madonna of Czestochowa, where the halos of Mary and the Christ child are colored in with rainbows. The Rainbow Madonna was designed by Elzbieta Podlesna, a Polish activist who had created and displayed the image while objecting to the idea that sexual orientation is “a sin or a crime.” Podlesna argued through the image that “the Holy Mother would protect such people from the Church and from priests who think it is okay to condemn others.” She created the image after observing a Easter display in her town of Plock in 2019. The display included “gender” and “LGBT” in a list of sins. She herself is not a practicing Catholic, but the image she created in response has been used by practicing Catholics promoting LGBT rights in Poland.

Blasphemy Laws

In May 2019, Podlesna returned to her home in Plock after an advocacy tour with Amnesty International. Police arrested her at 6am and searched her apartment. She was charged under Article 196 of the Polish Penal Code, which states:

“Whoever offends the religious feelings of other persons by publicly insulting an object of religious worship, or a place designated for public religious ceremonies, is liable to pay a fine, have his or her liberty limited, or be deprived of his or her liberty for a period of up to two years.”

The law is not as broad as many commentators make it out to be. Polish courts have exonerated a number of artists and activists charged under the law because of an inability to find the intent deemed required, or a failure to sufficiently meet the requirement that the offense be done “publicly.” Podlesna’s mere creation or any private sharing of the Rainbow Madonna image likely would not meet the code’s requirements. However, she had placed the image on display on church property in order to protest religious claims by local church leaders. It’s likely she will be convicted.

Poland’s Article 196 is a blasphemy law, something not unusual for a historically Catholic country. In some ways, the maximum penalty of two years in prison represents a liberal success. In 1531, under the leadership of Sir Thomas More as Lord Chancellor, England burned Richard Bayfield at the stake as a heretic. Commenting on such punishments for heretics, More said:

“The Catholic church did never persecute heretics by any temporal pain or any secular power until the heretics began such violence themselves.”

More saw the burning as something more or less requested by the victim. Five other heretics would be burned during More’s time as Lord Chancellor, three with his direct involvement. By the time of More’s death, one-fifth of the burnings of heretics in England’s history had taken place under his leadership. Drawing on these stories, some Protestant apologists also invented stories of More enjoying torturing heretics and engaging in other sadistic behavior towards his theological enemies.

The interesting thing about some of these burnings is the offense for them. The Tyndale Bible had been released, an English translation of the Bible which translated words in a way favoring the growing population of Reformers (“elder” instead of “priest,” and “congregation” instead of “church”). Bayfield was burned for distributing these bibles, and More later said that the heretic was “well and worthely burned.” More expressed similar sentiments after the burnings of others who kept or distributed the Tyndale Bible. Because of the centrality of religion to society, More and others saw blasphemy and heresy as forms of treason against both God and the state, justifying the most severe punishments. King Henry VIII eventually turned the violence of intolerance towards More himself, and the former Lord Chancellor was beheaded for treason in 1535.

On Blasphemy and Burning

It is in a certain sense that something like the Tyndale Bible could be considered “blasphemy.” Because of its novel translation of the Greek text, More and others believed that the Tyndale bible was engaging in the blasphemous act of speaking falsely about God. More had a developed concept and socio-political understanding of language, heresy, and blasphemy which informed his work as Lord Chancellor.

Unfortunately, today’s commentators are less discerning. “Blasphemy” today is used by many Catholics in much the same way as “heretic,” meaning “something/someone that I disagree with or don’t like.” Overbroad labelings by untheological armchair theologians completely skip over important theological debates (such as whether it is necessary for contempt to be explicitly expressed for a statement to count as blasphemy, and whether blasphemy can only be committed against God or could also be committed against others, such as the saints). These Catholic commentators do to “heretic” and “blasphemy” what they accuse many of doing to “racism”: using the terms in such an undiscerning and overbroad way as to deflate them of any real meaning.

The Catholic Catechism today says that blasphemy consists “in uttering against God – inwardly or outwardly – words of hatred, reproach, or defiance; in speaking ill of God; in failing in respect toward him in one’s speech; in misusing God’s name.” The Catechism sides with Bonaventure and Scotus (and against Aquinas) in concluding that blasphemy can extend “to language against Christ’s Church, the saints, and sacred things.” It specifically lists as blasphemous: “to make use of God’s name to cover up criminal practices, to reduce peoples to servitude, to torture persons or put them to death.” The last item in the Catechism’s list (to make use of God’s name to put persons to death) seems to prohibit the burning of heretics. The burning of a heretic is: putting someone to death in the name of God. In other words, the punishment for blasphemy appears to also be blasphemy.

Some Catholics quickly labeled the Rainbow Madonna as blasphemy, arguing that it is a political image advocating same-sex marriage, which is against the law of God. The image was created in support of LGBT people. But it’s easy to be sloppy about what this means. Conservatives tend to equate “LGBT rights” with “marriage equality” and the support of gender transition. However, the push for LGBT rights actually began with fighting discrimination in housing, healthcare, and other areas after people were refused care or housing on account of their sexual orientation. It began after LGBT people suffered violence. The Catholic Church has at times been a vocal proponent of LGBTQ rights. Pushing for “LGBT rights” in these areas is fulfilling the Catechism’s mandate that, for “homosexual persons… every sign of unjust discrimination in their regard should be avoided.” (Note that, not only must unjust discrimination be avoided, but even signs of such discrimination.)

Further, Catholic moral theology rejects the idea that “homosexual tendencies” themselves are a sin. Therefore, attributing to the Church the view that “sexual orientation” is a sin (as the Plock Easter display to which Podlesna had objected did) is itself be an act of blasphemy. The Polish church has blasphemed no less than Podlesna, and perhaps even more.

I, personally, am not a big fan of the “Rainbow Madonna.” As a work of art, it lacks the subtlety and sophistication I tend to favor. As a work of photoshop… it could be better. I also worry about co-opting cultural images to pursue social aims, however worthy they might be. The rainbow overlay in this case seems overly simplistic, crude, and appropriative.

But I’m not convinced that the Rainbow Madonna must be a work of blasphemy. It might be ill-advised to insert a rainbow overlay on historic cultural images’ halos, but it’s not necessarily blasphemy. As Fr. Matthew Schneider notes, halos are meant to represent the power of God. Fr. Schneider expresses concern about replacing “symbols of divine power with symbols of human power,” and similarly would object to a halo overlay with a sports logo, political symbol, or national flag. But on the other hand, one might argue that respect, compassion, and sensitivity towards LGBT persons is an expression of the divine power, which an image such as the Rainbow Madonna is seeking to portray.

This may not be the strongest argument, but I believe it ought to be taken seriously. And simply because many (most?) bearers of the rainbow flag advocate same-sex marriage, the symbol itself need not be rejected, as it still stands more broadly for the proposition that LGBT persons are worthy of housing, medical care, government services, and dignity generally. For similar reasons, I don’t oppose flying the American flag in Catholic churches (though neither do I advocate it). At the very least, the rainbow stands for God’s promise of a world to inhabit which will not be destroyed in divine vengeance, no matter how we might blaspheme.

In many ways, the lack of subtlety by many Catholics towards the Rainbow Madonna mirrors the lack of subtlety I believed the Obama administration had towards religious groups. I worried about an intolerance which would lead to injustice and provide a justification for violence. Every Obama supporter I knew rejected this concern. And even with these concerns at the time, I felt sure that the Obama supporters I knew would seek to safeguard me from violence, no matter how repulsive they might find my socio-political views.

I cannot say the same for some Catholics I know.

A Wish for Violence

I follow the God-forsaken world of #CatholicTwitter. I often contribute to it. Last week, an image of the Rainbow Madonna appeared on my feed. A European woman expressed exasperation on Twitter that the Polish law would send someone to jail for up to two years for bearing the Rainbow Madonna. In response, an American priest publicly commented:

“Absolutely unbelievable. Seems like too light a light punishment for blasphemy” [sic].

I commented back, tagging his diocese:

“@____diocese, just so you’re aware, you have a priest publicly saying 2 years imprisonment isn’t enough for having images like these in public. I have a similar icon, meant to invoke prayers from Our Lady for people like me. This priest wants me in prison.”

I later realized that the reason why the post came up on my feed was because a Catholic friend of mine (a fellow Notre Dame grad) had shared it. I realized that a friend would advocate my imprisonment because I sought to invoke respect, compassion, and sensitivity for LGBT persons through an icon with a rainbow overlay. This was more shocking than the Twitter priest’s advocacy. The friend is hardly an extremist. I now wonder how many other Catholics would advocate my imprisonment. I now know from experience that American priests can advocate this publicly.

I never got a response from the priest, the diocese, or the friend. But #CatholicTwitter did show up. I received responses largely from profiles with Vatican flags in their names, and which I’m assuming had a connection to the Twitter priest, since I don’t typically get this sort of engagement. One responded with a meme saying:

“Shut the f*** up.”

Another said:

“In that case, you should definitely be in prison.”

Another said:

“don’t you DARE attack fr. ______!”

Another commented:

“Prison? I was thinking more violent punishments.”

In response to these comments, neither the priest nor his diocese said anything. That friend which I mentioned earlier blocked me and hasn’t spoken to me since.

I never thought that engaging with a priest online would result in a wish for violence against me. One might be inclined to dismiss these sorts of commenters as isolated impotent miscreants of the dark web. But we know from the Capitol riot that these sorts of commenters are real people, emboldened by religious rhetoric, and ready to sow violence when they gather together.

Over the years, I’ve found a shift in my concerns for safety. I once feared that liberals would attack me because I openly opposed their policies. I now fear that other Catholics will attack me because of their lazy theology. They feel quite comfortable wishing as much. I no longer fear secular liberals. I fear other Catholics. They wish me harm. The Twitter priests sit back and do nothing. Or they stoke the flames from their parish offices.