Newsletter #17: parenting the non-rational soul

In today's newsletter: angering Catholic twitter, being second choice, sleeping in airports, and Freud-as-Aristotelian

Happy Tuesday! Here’s what else is in the newsletter today:

I’ve angered Catholic twitter

On being second choice

How to sleep in an airport

What I’m reading: Freud, Aristotle, and the non-rational soul

I’ve angered Catholic Twitter

Last week’s essay discussed natural family planning, Putin’s religious and cultural ideals, and Christian rhetoric concerning suffering. The piece had what is probably the most provocative title thus far on this site: “NFP culture sometimes resembles a pagan death cult.” The essay infuriated parts of Catholic twitter, probably because I did not do enough to highlight the “sometimes” and “resembles” in the title.

I did receive thoughtful responses, including some helpful critiques and correctives (a couple of which I added to the end of the essay). The majority of the criticisms, however, were not helpful. They fell into a few groups: some attributed views to me that I don’t hold, some personally attacked me (by name-calling or other means), some complained that I chose to highlight a particular set of experiences rather than another, some “critiqued” me by making statements that I actually agree with, some took “sometimes resembles” to mean “equates,” some said they just didn’t get it, and some accused me of bad faith or simply lying.

Perhaps I should clarify what the piece was doing and what it was not doing. It was highlighting the experiences of a group of women who shared their struggles with NFP, Catholicism, and purity culture with me. It was not presenting those stories as the universal experience of Catholics when it comes to NFP. The essay was arguing that certain rhetoric in the NFP space resembles certain dispositions that Putin has towards the suffering of his people. It was not arguing that general promotion of NFP is the same as Putin-style masochism. It did share the experiences of women whose husbands received vasectomies. It did not argue that the Church should change Her teachings, or encourage violating Church teaching.

I do recognize that the analogy of certain NFP rhetoric to Putin’s rhetoric was provocative. (I once compared Obama’s policies on abortion to Nazi policies which, looking back, was not a good rhetorical move, even if it made sense to me.) The Putin analogy didn’t work for everyone. I would argue, however, that this failure was more due to a lack of imagination than to the weakness of the analogy. For the women who shared their difficult experiences with me, the analogy made sense and, according to them, was helpful and illuminating. So the question of whether one can make sense of the analogy is, in part, a question of whether one can empathize with the sufferings of these women.

This is part of the challenge of the piece: can you expand your imagination enough to fully engage the experiences of these women, or does your imaginative landscape fall apart before you get to that point? Is your imagination developed enough so that you can understand why they found the analogy helpful, why it made sense to them? If not, then you won’t be able to really understand their experiences. Once we reach that imaginative point, we can have a meaningful conversation about the strengths and weaknesses of the analogy. But if we can’t get there, we can’t have real discourse on the issue. All we have to work with are power dynamics.

But the incentive structure of social media doesn’t help open up imaginative landscapes. Part of the perversity of social media can be observed in the fact that the angriest objections to the piece were also what drove its greatest promotion. The response which drove the most engagement, readership, and new subscribers to my site was the angry name-calling of a blue-checkmarked Catholic writer:

Part of the issue with many Catholics is that they find vasectomies morally abhorrent. What this means in practice is that they are unable to engage in moral discourse with most people about vasectomies. MacIntyre discusses these dynamics in the early chapters of After Virtue, where he says that part of the problem with abortion discourse is that it’s not really discourse. Instead, the sides are so repulsed by each other that they end up just emoting over the other side of the fence. They end up expressing little more than preferences back and forth at each other. It is only when we can establish a different dynamic that we can engage in actual discourse.

These sorts of engagements have taught me how incredibly challenging it can be to have thoughtful and respectful dialogue on difficult topics in the Church. Angry outbursts drive more engagement than calm considerations (for both the giving and receiving sides of the outbursts). This occurs partly because indignant anger is pleasurable. It feels good to be angry, which is partly why we seek out (and our social media feeds highlight) what makes us mad. These dynamics condition us to seek out these interactions, by rewarding us with engagement when we provoke or participate in them.

I’m certainly not innocent here. The last week has given me a lot to think about when it comes to these questions. But when it comes to the essay in general, I’m just really grateful to the women who shared their stories with me. I hope that continuing to share these stories can lead to a better care for women and families in the Church.

On being second choice

Last week, I had the opportunity to represent my company at a Procurement Leaders conference. I was sent because I had joined the company in a new leadership role. This gave me the opportunity to reflect on the value of being second choice.

People know I completed my undergraduate studies at Notre Dame. What they often don’t know is that I was originally waitlisted. So when I started college, I knew that (from an admissions perspective) I was in the bottom 50 students in my class. I also know that I wasn’t the first choice for my current job. The role was originally offered to someone else, and then I got the offer when that didn’t work out.

I could feel embarrassed by all this, but I’m proud of it. These opportunities have pushed me to prove myself. When you’re not first choice, you’re pushed to work harder. You can’t have a sense of entitlement. Gratitude is easier, because you often know that someone saw something in you and decided to take a chance on it. (You may have been the out-of-the-box candidate.) And it’s easier to encourage people who are struggling in their careers to persevere. Because you know the power of perseverance. I think I’m a great candidate for challenging opportunities, because I know from experience that I can embrace failure and rejection and use them for long-term success.

Being second choice has also helped me reflect on the value of humility. When I was originally rejected for the job, I reached out to the hiring manager and said that if things changed, I’d still love to be considered. And that’s what happened. Because I could swallow my pride, and be willing to be second choice, I was able to hold onto an opportunity. And in the end that’s what matters: not whether you were first choice, but whether you could persevere in the face of rejection.

These are all key values that speakers at the conference highlighted for procurement: humility, resilience in uncertainty, and a focus on long-term winning. It was an affirmation of the ways I’ve chosen to pursue my career and develop as a person. And it was an opportunity to be grateful for the people who have taken a chance on me.

How to sleep in an airport

I had the craziest travels back from the conference in Miami this weekend. I was supposed to take off in the early evening and have a short connection in Atlanta. But first we were delayed because it was taking them forever to get our bags on the plane. Then we were delayed because (after we were already on the plane) one of the pilots got suddenly very ill and they had to find a replacement. I learned that airlines plan for this sort of thing, and a replacement was eventually located.

But by the time of our new scheduled departure, I knew I was going to miss my next flight. I wondered about maybe just staying in Miami another night, but I looked up alternatives and realized that I wouldn’t be able to fly out for another two days. So I needed to get out of Miami. I also needed to get out of Miami to escape the Gen Z spring breakers:

Delta was able to get me on standby for the last flight out of Miami, so I had them book me on it, with a flight the next morning as backup. During this whole ordeal, I was befriended by a boisterous middle aged lady from Wisconsin (we’ll call her “L”). I live-tweeted my unfolding friendship with L, which was truly an unforgettable experience. You should check it out. (Seriously, it’s wild):

Anyways, we made it to Atlanta, and L was able to get off of standby and get home, but I was not. But not only this. Every hotel within 30 minutes of the airport was sold out. So I had to sleep in Terminal B. I asked Twitter for recommendations, and was able to get some good advice. If you’re wondering, this is how you make the best of it:

Secure an outlet. (If the airport is busy, do this ASAP).

If you go to the airline’s help desk, they often have blankets and overnight kits they will give you for free. If a souvenir shop is open, consider just buying a sweatshirt and blanket - it costs less than a hotel. If you see a family with small children, give your free blanket to them — don’t be a monster.

Buy your snacks before things close.

The massage chairs aren’t bad for sleeping in. Plus, you can begin your sleep with a 30 minute session. If you can grab one before they’re all taken, some of the lounge areas also have couches.

Maybe don’t worry about sleeping in your assigned gate. It may change 2-4 times throughout the night (as mine did).

If you have a KN-95, you can pull it up and wear it as a face mask that covers mouth, nose, and eyes. (I was very proud of myself when I discovered this).

Be nice to the airline and airport staff. It’s not their fault, and people have probably been super rude to them as events have unfolded.

What I’m reading: Freud, Aristotle, and the non-rational soul

In recently started reading Jonathan Lear’s book on Freud (titled: Freud). The book opens by placing Freud and Aristotle in conversation. Freud had focused a significant portion of his university studies on Aristotelian philosophy, studying under Franz Brentano. And Lear sees Freud as exploring the mind and developing psychoanalysis through a largely Aristotelian mode. Like Aristotle, Freud chose to focus on the small realities of the world to uncover profound discoveries about the meaning of human existence.

Future newsletters will likely discuss various portions of Lear’s book. But for now I will just focus on a footnote in chapter one, where Lear discusses Aristotle’s vision for obedience of the non-rational part of the soul:

“The non-rational soul, he [Aristotle] says, participates in reason as though it were listening and obedient to a father… This is a patriarchal image, and that raises problems of its own, but there is something thought-provoking in Aristotle’s idea that the non-rational soul is essentially childish. It is as though it is permanently en route to maturity; but its excellence does not consist in actually reaching adulthood. Rather, the excellent non-rational soul is an excellent instance of a childish soul. Its excellence consists not in ‘what it will be when it grows up’, but in a distinctively non-rational ability to listen to and communicate with reason. The external, social model of intra-psychic speaking-with-the-same-voice would thus be excellent parent-child communication. The excellent child is excellent at attending to his parent’s communication; the excellent parent is excellent not only in knowing what to say, but in how to communicate it to a child.”

One implication of this view is that part of what the non-rational soul (or non-rational part of the soul) needs is room to play, to be childish, to be itself. And part of what reason needs is to learn. Reason will not immediately know how to engage the non-rational part of the soul, unless it gives that part of the soul room to play, respects that it has a certain amount of autonomy, and doesn’t stifle it or seek to replace the means and ends of the non-rational soul with its own. One of key ways that a parent can harm a child’s development is by being over-controlling.

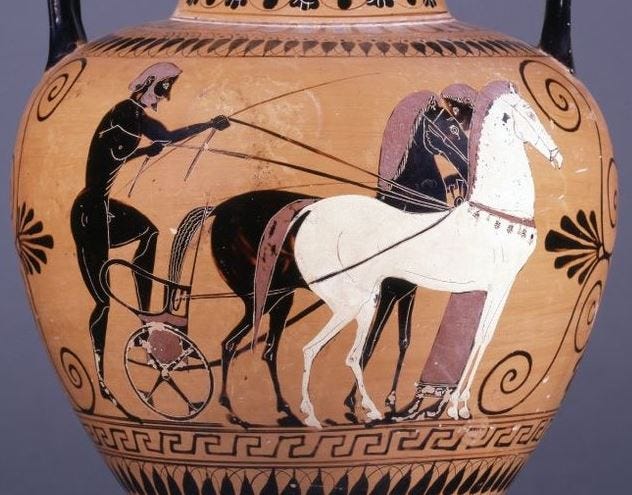

This is similar to Socrates’s treatment of the soul in the second speech of The Phaedrus.1 In that speech, Socrates says that the soul’s form resembles “the composite nature of a pair of winged horses and a charioteer.” The role of the charioteer is often misunderstood because of translation issues. While Helmbold and Rabinowitz’s translation says that the charioteer “dominates” (“ἡνιοχέωhold”) the pair of horses, Fowler more literally translates to say that the charioteer “drives” them. (“ἡνιοχέωhold” is associated with the work of a charioteer and means to “hold the reins” or to “direct” or “drive” or “act as charioteer.”) The charioteer must be skilled and know how to work with the horses, lest the horses “have their wings broken through the incompetence of their charioteers.” Here the image is not one of total dominance, but moves towards a vision of control which respects the nature, autonomy, and unique needs of the horses.

One of the horses is “noble and handsome and of good breeding” and is shy when faced with beauty. The other horse is “the very opposite,” a “great jumble of a creature… hardly heeding whip or spur,” and when it sees beauty, it forces the group forward to attain the gratification of Aphrodisial pleasure (“ἀφροδισίων”). The work of the charioteer involves engaging what is best in each horse so as to seek after true union with beauty, while not consuming or defiling it.

Under both the Aristotelian and Platonic visions, the non-irrational part of the soul is not simply to be dominated through the autonomous implementation of the parent/charioteer’s vision. Rather, the parent must understand and treat the child as a child, and the charioteer must understand and treat each horse as a unique horse. The dynamic is not one of tyrannical slave-driver, but of a listening and attentive parent and chariot-driver.

This challenges much Christian discourse on sexuality that alleges to derive from the Aristotelian tradition. If erotic desire belongs to the non-rational part of the soul, to the child and the unruly horse, Plato and Aristotle’s vision does not suggest one must simply silence and dominate. Instead, they suggest one must get to know it, create spaces for it to grow and develop, and allow it to flourish according to its own nature. The non-rational part of the soul is not simply the enemy or opponent of reason, as much Christian discourse seems to suggest, but an important part of human nature that must be embraced and cultivated if reason is to be what it is meant to be. It is not just that a child needs a parent and that a horse needs a charioteer; the opposite is also true. A parent cannot be a parent without a child, and a charioteer cannot be a charioteer without a horse. Without the non-rational part of the soul, human reason will fail to achieve its own excellence.

You can follow along with my current reads at Goodreads.

Now accepting submissions!

If you like what I’m doing here and want to join in this developing project, I’d love for you to submit an essay, poems, or a short story for consideration. You can learn more here.

Follow Along

And that’s all I have for you today. If you’re on social media, you’re welcome to also follow me at Twitter and on my Facebook page.

The translations used here are a mix of the Helmbold and Rabinowitz translation published by MacMillan, the Fowler translation associated with the Perseus Project, and my own translations.

Do you feel the "silence and dominate" approach to sexuality is what the Church teaches? That's never what I got from it, but my perspective is different as well. If eros is to become what it truly is, we must understand eros is not strictly sexual. If we let eros be unguided, it most becomes dominant over reason and thus distorted, no longer like a child playing and being himself, but a child telling his father what to do. The language of chastity in the catechism doesn't seem to me to indicate a total "dominance" from the onset because the phrases included in the Catechism starting at 2337, such as "integration," "long and exacting work," "laws of growth", "stages marked by imperfection" and by its rejection of "mere external constraint." (Starting at P2337.) It could be perhaps that I am misunderstanding you as well.

The critical comments toward you only show the critics didn’t carefully read your article.