“Bishop Barron wasn’t involved”

Neither the law nor lawyers should provide the basis or boundaries for the Church’s moral obligations.

Many angles can be used to explore the recent controversy surrounding Word on Fire’s firing of Joe Gloor. I have written on and shared stories about the issues of sexual misconduct, employee intimidation, additional harm to the victims, workplace misogyny, and the violation of boundaries. In addition, this site has also reviewed Word on Fire’s second public statement on the matter through the lens of a communications professional and provided recommendations for change. And I have looked at how focusing on chastity can compound problems. One angle yet to be explored is the role of an attorney and investigator working for the Church.

In the present case, an external professional was hired by Word on Fire to handle the investigation process into Gloor’s alleged sexual assault and abusive sexual behavior. This was stated repeatedly by the organization, as it was questioned for a mishandling of the matter. One of the most striking portions of Word on Fire’s May 6 public statement on the issue was: “The truth of the matter is that the process of investigating and dismissing the employee was conducted by a sub-committee of the board and not by Bishop Barron. He couldn’t have mishandled the situation since he was not handling it at all.” According to the statement, a sub-committee of Word on Fire’s board of directors spoke with some of the women, and then retained legal counsel, who then engaged an investigator. The statement said, “Bishop Barron was not involved in these activities.”

Certainly the organization was right to hand over the investigation to an experienced and objective outside third party. Given the close relationships between Gloor and many of the leaders at Word on Fire, it would be inappropriate and unjust for the investigation to be handled by the ministry’s internal management team. (For example, according to Bishop Barron’s comments in a transcript of an October 13 staff meeting, Barron had been having dinner with Gloor on a weekly basis.) Seeking external support for the investigation was necessary. This, of course, is one key learning from the clergy abuse crisis: when those evaluating complaints of sexual violence or impropriety are too close to the alleged perpetrator, they are often inclined to take his side and to dismiss the victims, risking additional harm to the present victims and also harm to potential future victims. One way to ensure a fair investigation is through the use of an external third party.

If a fair investigation conducted by an “objective” third party is the only goal for a Catholic ministry, diocese, or other institution, then engaging a third party may constitute the entirety of its duties in these situations. But I would argue that this is not, and cannot, be it.

There is no tabula rasa third party

In any event, this was not what happened with Word on Fire. The third party investigator, according to an October 11, 2021 letter from Word on Fire’s attorney that was made available to me, reviewed the complaints of the victims and independently established the scope, means, and manner of the investigation. But one does wonder about this scope. It appears that either the investigator or Word on Fire chose to treat the complaints of the women as entirely isolated from the work of the ministry, and thus did not seek information from staff members who could have provided significant assistance. Consider this exchange from the October 13 staff meeting:

Staff member 1: Yeah, but, I'm also concerned about fairness to the rest of us. Because this was happening at work. Not in the office, but it was happening on work trips.

Staff member 2: Yup, it was happening on work trips, and it's been stated that he's used his position at Word on Fire to manipulate these women.

Barron: All that was taken into consideration in the investigation, that all came forward, now, I didn't know about that. I mean, if Joe was doing that stuff when he was on the road, I didn't know about it. What is—

Word on Fire may not have examined workplace misconduct, because the staff was not asked whether they had observed issues or problems related to Gloor. According to the meeting transcript and subsequent statements by staff members, a number of the staff had concerns related to Gloor that they had attempted to raise but which were never seriously considered by Word on Fire. I have spoken with multiple women at Word on Fire, none of whom were invited to provide feedback regarding issues of harassment, abuse, sexism, or misogyny during the investigative process.

But regardless of that particular failure, the actions and advice of Word on Fire’s attorney who engaged the investigator were shaped by the perspectives and frameworks provided by the ministry. For example, consider another exchange between Bishop Barron and a staff member during the October meeting. A staff member during the meeting raised how Gloor admitted to being “unchaste,” in contradiction to Catholic teaching. In response, Bishop Barron said: “And we used that language throughout. We often had to explain it to the lawyer what that means, to say someone is acting unchastely.” That is, while the investigator may have acted independently, outside counsel (who guided the ultimate decision-making and provided final communications to the victims) was expected to operate within the perspectives and frameworks established by Word on Fire. (I wrote more on that here.)

Thus, the investigation, conclusion, and results did not simply operate out of the “objective” and removed frameworks, methodologies, and understandings of sexual or other misconduct established by third parties. Rather, Word on Fire filtered these all through a particular perspective–its presentation of Church teaching–and expected them to operate under that perspective.

When the solution further harms

It is perhaps the focus on chastity which led Word on Fire’s leadership to act as if their responsibility towards the victims was complete with the conclusion of the investigation. If the problem was Gloor’s interior life, rather than what the women in the present situation suffered (and how they continue to suffer), then Word on Fire had no responsibility towards the victims other than an investigation and disciplinary action towards Gloor. This approach may have contributed to additional harm.

For example, at the conclusion of the investigation, Word on Fire’s attorney communicated to one of the victims that Gloor might be returning to work. Upon reading this, the victim shared portions of the letter in a private group message. According to my source, a woman in the group, without the victim’s permission, shared this with her husband, a Word on Fire employee. The husband then shared the information with Word on Fire’s CEO Fr. Steve Grunow. Bishop Barron, according to the October meeting transcript, was led to believe that the victim had posted her story on her “facebook page.” The Board had yet to make a final decision on Gloor’s employment status, but based on this supposed post, Word on Fire terminated Gloor at that time. When asked about whether Gloor would have been terminated without this supposed post, Barron told his staff, “Well, I can’t say absolutely for sure.” (This was even after Word on Fire had been provided photographic evidence of Gloor exposing himself at the home of one of the victims without her consent, and, according to one of the victims, being made aware of police reports that had been filed against him for other incidents.)

Nonetheless, Gloor was terminated within 18 hours after Word on Fire mistakenly believed the victim had posted her story on social media. None of the victims were made aware of Gloor’s termination beforehand. According to one of the victims, Gloor had been made aware of the supposed Facebook post and threatened another one of the women if she did not encourage the victim who had posted it to take it down. It is unclear how, why, and to what extent Word on Fire shared details of the investigation and the participation of the victims with Gloor. After being made aware of that “facebook post,” he started reaching out to all of the victims, including one victim who had asked to remain anonymous and did not participate in the full investigation.

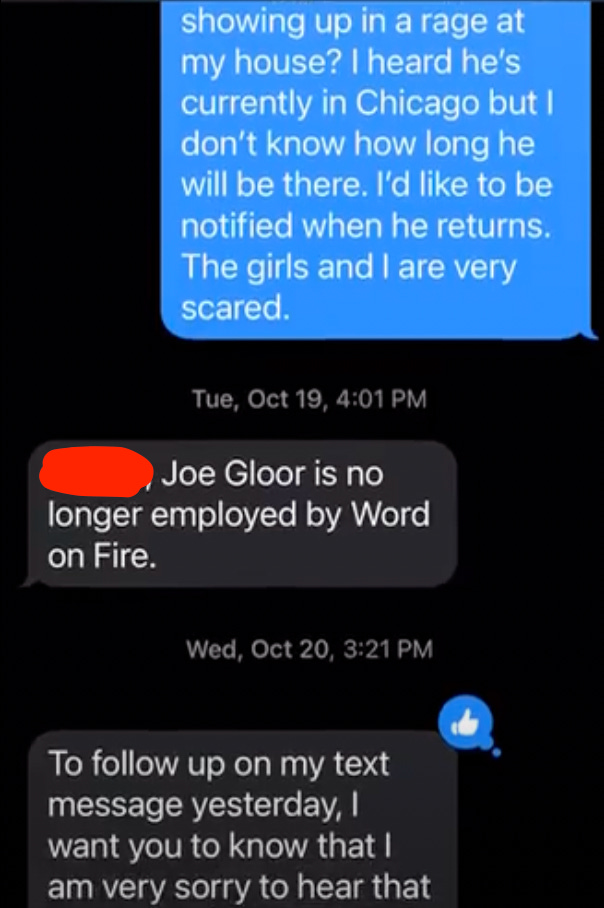

The victims were afraid of him. And their fear was validated. They didn’t know he had been terminated when he began harassing them. The week after the termination, one of the victims communicated to Mike Benz, a member of the Word on Fire Board of Directors:

“Hey mike

Just trying to understand what happened and if my life is still in danger. The letter I received a week ago today (Tuesday) from your attorney said that you were not firing Joey. That same night he contacted each girl who sent in a statement - including the anonymous statement girl. He was sending me weird messages blaming me for everything. Then he showed up at my house 16 hours after I received the letter. Joey lives four hours away from me. So I called the police to get him to leave. He was yelling and screaming and saying he lost his job. Why did the letter say he wasn’t going to get fired, then he was fired. So at this point I don’t know what’s true. It’s very confusing and scary because he showed up at my home - meaning he drove in the middle of the night to my house. What happened from me receiving the letter to him showing up in a rage at my house? I heard he’s currently in Chicago but I don’t know how long he will be there. I don’t know how long he will be there. I’d like to be notified when he returns. The girls and I are very scared.”

Three and a half hours later, Benz responded:

“[Name], Joe Gloor is no longer employed by Word on Fire.”

He then let her sit with that response for 24 hours. Neither he nor Word on Fire reached out to offer any support or sympathy.

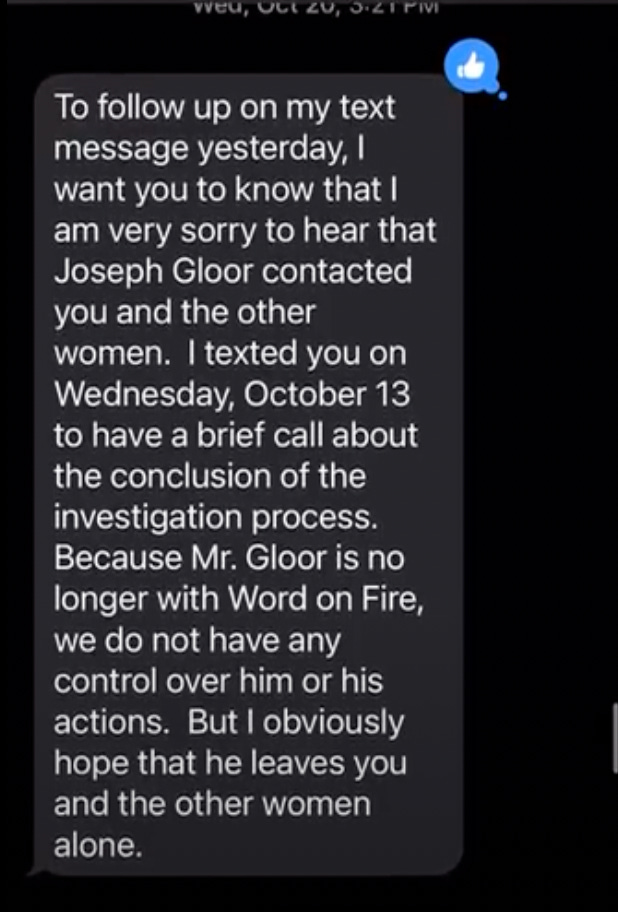

To his credit, Benz did send a follow-up the next day:

“To follow up on my text message yesterday, I want you to know that I am very sorry to hear that Joseph Gloor contacted you and the other women. I texted you on Wednesday, October 13 to have a brief call about the conclusion of the investigative process. Because Mr. Gloor is no longer employed with Word on Fire, we do not have any control over him or his actions. But I obviously hope that he leaves you and the other women alone.”

The two messages from Benz do not seem to be drafted by the same person (one refers to “Joe Gloor” and the other one to “Joseph Gloor” and “Mr. Gloor”). Nonetheless, it’s important to note that what Benz is communicating here is: “I hope Gloor leaves you alone, and, as far as we are concerned, you are alone.” Benz did later share with the victim some of Gloor’s whereabouts, and offered to provide additional information as it became available. But the most immediate reaction to the victim sharing how she is afraid for her life was not one of compassion or support.

Benz likely did not intend to dismiss the victim, and Word on Fire likely didn’t intend for Gloor to begin harassing the women as soon as he was terminated. But, again, this demonstrates how organizations that are not well equipped to work with victims can compound harm. I often come back to a clergy abuse survivor who once told me that, when it comes to working with victims, “You can wound with just incompetence. There doesn’t have to be malice.” Maybe, as their May 2 statement said, “Word on Fire and Bishop Barron have been leading voices for accountability in the Church.” But they are certainly not leading voices for victims. This all shows how utterly unprepared both Barron and Word on Fire are to deal with victims.

The research on investigations

It is not uncommon for workplace investigations into sexual misconduct and harassment to result in additional harm to the victims. In 2020, the Harvard Business Review published an article titled “Why Sexual Harassment Programs Backfire.” In the article, sociologists Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev shared their research into more than 800 companies. Their study revealed that “[n]either the training programs that most companies put all their workers through nor the grievance procedures that they have implemented are helping to solve the problem of sexual harassment in the workplace. In fact, both tend to increase worker disaffection and turnover.” And after the implementation of training programs on forbidden behavior, the representation of women in management in these companies decreased. Dobbin and Kalev drew on research finding that these programs sometimes worsened the treatment of women, making “men more likely to blame the victims and to think that women who report harassment are making it up or overreacting.” And they noted research that has found that “men who are inclined to harass women before training actually become more accepting of such behavior after training.”

The article also noted that grievance procedures for sexual harssment provide little help. The companies in Dobbin and Kalev’s study had a decrease in the number of women in management after the implementation of grievance procedures. This was especially so in companies with few female managers, because “women are more likely than men to believe reports of harassment.” The grievance procedures often backfired, resulting in retaliation against victims who came forward in a system where “most procedures protect the accused better than they protect victims.” At times, women would initiate the grievance process, experience retaliation, and then quit before the process was complete. To reduce workplace harassment, Dobbin and Kalev recommended more effective strategies, such as manager training, bystander-intervention training, the implementation of an ombuds office, voluntary dispute resolution, an option to avoid, train-the-trainer programs, harassment task forces, and publishing statistics on harassment. (Some of these were included in the list of recommendations for Word on Fire.)

Dobbin and Kalev’s findings can provide guidance beyond the specific issue of sexual harassment within the workplace. And they can speak directly to the issues that have been raised at Word on Fire. On the one hand, their article noted that trainings and protocol may not do much to curb harmful behavior of those who harass and or who make light of harassment. On the other hand, real harm is caused to those who have to endure harassment and who must engage in grievance procedures that are not sufficiently designed with victims in mind. An organization which relies too heavily on its protocols for protection can lose sight of what victims actually face and compound the harms they have suffered.

This seems to be what has happened at Word on Fire. During the grievance process, Word on Fire management provided information to the perpetrator which led to additional harassment and threats to the victims. And during the October staff meeting, Barron openly entertained the idea that the victims may have come forward because of animus towards the ministry. A staff member asked Barron about the timing of the complaints and whether the victim had animus towards Word on Fire or whether someone else was “behind this.” Barron responded: “Yeah, honestly, I don’t know. Yeah, it’s a fair question.” Note that he said this, even after the victims had vulnerably entrusted their stories to his ministry and their investigator had determined that the women were victims.

Also consider what Barron said when a staff member noted that two police reports had been filed against Gloor, and the victims could choose to press charges:

“Fine, I mean, that's her prerogative, obviously. It's a free country. But I, I'm not the agent of pursuing criminal investigations. If she wants to do that, fine. I think what matters for us is that we ended our relationship with Joe. If [victim's name] wants to pursue criminal charges, it's a free country.”

Barron offers a dismissive attitude towards the victims: “It’s a free country.” And he said: “What matters for us is that we ended our relationship with Joe.” Barron communicates that what is most important to him is that this is not his problem anymore. He does not see the victims as victims even after they have gone through this difficult grievance process. He does not see that he has caused additional harm by disclosing one of their identities to his staff without her consent. And he believes he has no additional obligations towards them.

A repetition of issues

As I noted previously, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops adopted the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People in June of 2002, as a response to that time’s round of clergy abuse scandals. The Charter created the National Review Board for the Protection of Children and Young People and directed it to “commission a comprehensive study of the causes and context of the current crisis.” In February of 2004, the National Review Board published that report.

The report listed key causes for the failure of Church leaders during the crisis, including:

a failure to “understand the broad nature of the problem” and “treat[ing] allegations as sporadic and isolated”;

allowing a “fear of scandal” to cause them “to practice secrecy and concealment;”

an over-reliance on legal counsel in dealing with a problem which “at its heart [was] a problem of faith and morality”;

a focus of the “threat of litigation” which “caused some bishops to disregard their pastoral role and adopt an adversarial stance not worthy of the Church”;

a failure to sufficiently provide “‘fraternal correction’ to ensure that their brethren dealt with the problem in an effective manner”;

and placing “the interests of the accused priests above those of the victims.”

A preoccupation with legality and legal advice is a common theme for a number of these issues. Placing too much reliance on lawyers always puts the Church at risk of failing in her mission. Robert Vischer, a Catholic lawyer and law school dean, has written how the legal profession has its own morality, and an over-deference to the legal profession has at times led to a replacement of the Church’s pastoral morality with the legal profession’s adversarial and rights-maximizing morality. Engagement of legal or other external professionals in the face of a crisis can never be sufficient for the Church’s response, because such engagements must always involve some level of management by the Church, partly to ensure that professionals engaged by the Church contribute to the Church’s mission (or, at the very least, don’t act contrary to that mission), and partly because the scope of a professional’s role can never encompass the entirety of the Church’s responsibilities.

Again, in its May 6 statement Word on Fire alleged: “[Bishop Barron] couldn’t have mishandled the situation since he was not handling it at all.” It’s important to note, however, that Bishop Barron is the founder of Word on Fire and a member of its board of directors. Word on Fire had recently undergone a rebrand such that many of its communications used the name: “Bishop Barron’s Word on Fire.” Word on Fire presents itself as his ministry.

Word on Fire’s statement would be similar to my Archdiocese becoming aware of misconduct within the chancellery, hiring an outside firm to investigate, and then saying, “The Archbishop couldn’t have been responsible for mishandling the situation since he was not handling it at all.” Church leaders cannot wash their hands of problems by simply outsourcing them, with no responsibility for the process or the outcome. Rather, leaders must take some level of responsibility for problems that arise, whether they were directly involved or not, and must take a significant level of personal responsibility for their resolution.

In their actual approach, Bishop Barron and Word on Fire seem to be repeating the very dynamics which the National Review Board saw as center to the Church’s abuse crisis in 2004. Barron and his ministry seem to treat the issue as primarily a technical problem to be handled by outside experts, rather than a problem that strikes at the core of Catholic faith, morality, and our ecclesial life (in which outside experts can provide key assistance in helping to understand and respond to particular issues under the umbrella of a broader problem). The NRB report noted that Catholic leaders wrongfully relied “on attorneys who failed to adapt their tactics to account for the unique role and responsibilities of the Church.” This underscores how the handling of issues by outside experts must always involve some level of handling by Church leaders.

Care for victims

A key failure for a Catholic bishop and leader of a national Catholic ministry in this situation was a failure to reach out to the victims. As he shared in the meeting, Bishop Barron had not reached out to any of the victims who came forward, even after the conclusion of the investigation and the firing of the employee. Barron today might be the bishop that is quoted in the NRB report:

“We made terrible mistakes. Because the attorneys said over and over ‘Don't talk to the victims, don't go near them,’ and here they were victims. I heard victims say ‘We would not have taken it to [plaintiffs' attorneys] had someone just come to us and said, ‘I'm sorry.’ But we listened to the attorneys.”

But Barron never reached out to the victims. According to one of the victims with whom I have spoken, he still has not. There are two key differences between Bishop Barron and the bishop who participated in the NRB report. First, Bishop Barron does not think he has made a mistake. Second, and because of this, there is no indication that he would act any differently in the future. He has missed the following recommendation from the NRB report:

“All bishops and leaders of religious orders should meet with victims and their families to obtain a better understanding of the harm caused by the sexual abuse of minors by clergy. Bishops and leaders of religious orders must be personally involved in this issue and not delegate a matter of such importance to others.”

This should not be limited to clergy sexual abuse of minors. This is also relevant when the Church’s ministers abuse, especially when such abuse is furthered or enabled by their positions of leadership. Apologies and direct support for victims should occur, even when attorneys advise otherwise. The NRB report also stated:

“Many diocesan attorneys counseled Church leaders not to meet with, or apologize to, victims even when the allegations had been substantiated on grounds that apologies could be used against the Church in court. The Review Board believes that offering solace to those who have been harmed by a minister of the Church should have taken precedence over a potential incremental increase in the risk of liability.”

Justice, protocol, and going forward

Indeed, in this instance, Word on Fire and Bishop Barron seem to be more focused on protocol than on the victims. Protocol should be enacted for the purposes of achieving justice for all parties during and after the process, especially for victims. Protocol acts in the service of justice. However, protocol is never sufficient on its own for the achievement of justice. An overreliance on process can often function to dismiss the victims as victims, treating them instead as mere participants in an HR exercise, and compounding harms even if the process has concluded with a decision in their favor.

Consider, again, Mr. Benz’s response to one of the victims who has expressed fear for her safety. Because she has bravely come forward, helped Word on Fire to identify serious misconduct on the part of one of its most prominent leaders, and participated in the investigative process, she was put into a position where she feared for her safety. Her participation in Word on Fire’s protocols, and her open discussion of them at their conclusion, should not compromise her safety. And yet it did.

But “don’t add danger or harm for the victims” should only be a baseline requirement, and should not be treated as the Church’s only or primary obligation. Nor should “adherence to policy” or a “fair investigation” be treated as such. Instead, a victim coming forward should be treated as a victim, as someone entrusting a story of deep vulnerability to the Church and her ministers, deserving of love, compassion, and support.

This should be the focus of any and all policies in this area. The mark of a good policy is not whether the investigation yielded a result in which an actual perpetrator was removed. Rather, the mark of a good policy is the holistic experience of the victim as a full person who has likely undergone one of the most difficult experiences of his or her life. These processes should not compound harm for victims. They should always support healing and empowerment. This is partly why these processes should always involve an invitation to the victim to conduct a post mortem, regardless of the conclusion. The Church would do well to consider these concerns, and develop resources so that her institutions can behave accordingly.

Going forward, Catholic institutions should recognize that addressing sexual violence and other harms perpetrated by its leaders will always be a messy process. Each situation will be unique, and thus part of the process to address harms should involve a reflection on established process and protocol. Particularly after the conclusion of an investigation, victims should be consulted and provided an opportunity to make recommendations.

Catholic institutions should also recognize that the engagement of outside experts will often be a messy process. Experts should be utilized for their expertise, and should be given the freedom necessary to fulfill their roles well. But issues of sexual violence or other harms will never be mere technical problems that can be handled entirely through the use of experts. The institution involved will always have some level of oversight, whether it recognizes this or not. There are key tensions here: between insufficient oversight and micromanagement, between the freedom necessary for each role to be fulfilled and the guidance necessary to ensure the Church’s mission is fulfilled, and between respecting the caring for the vulnerable stories of victims and the need to respect the rights of the alleged perpetrator. These are not tensions to be hastily dissolved, but to be carefully managed and regularly revisited.

Because of the challenges with these sorts of situations, probably the most important virtue for Catholic institutions and their leaders will be humility. The risk of getting things wrong is very high in these situations, and Catholic leaders should recognize this. We may not get it right every time, but we must always try. And we must be willing to be accountable for our mistakes.

More on this controversy:

As someone who in the past has had direct experience in the case of young children who had been subjected to sexual abuse only to have a bishop and his lawyer turn a stone cold face to the situation, I could not agree more with what is written here! It is not the gospel that is guiding us but fear of litigation. Shame!

Excellent article! Writer carefully evaluated the actions or inactions, taken by Bp Barron, in response to the sexual abuse and harassment. Bp Barron acted in a despicable manner.