How chastity enables sexual violence

Word on Fire may be helping to revive parts of the clergy abuse crisis.

Word on Fire’s recent controversy concerning the termination of its executive producer Joseph Gloor provides an opportunity to examine the ways that sexual violence (including sexual harassment) are addressed by the Church. Change is needed. And Catholics must be attentive to dangers specific to the Church. A misuse of the Church’s moral theology can enable and compound harms, as we learned from the clergy abuse crisis. In particular, some preoccupations with chastity can represent a fundamental misunderstanding of the issue of sexual violence, and this focus may enable and perpetuate such violence, especially against women. A better treatment of both chastity and sexual violence is needed for the Church to move forward from fundamental mistakes that were made throughout the clergy abuse crisis and that continue today. Word on Fire’s present controversy provides a helpful case study.

The Word on Fire controversy

In August of 2021, four women raised complaints with Word on Fire alleging sexual assault or abusive sexual behavior perpetuated by its executive producer Joseph Gloor. A number of details have been shared elsewhere. For the purposes of this discussion, I will focus on the role that “chastity” played in Word on Fire’s investigation and the ensuing events.

According to Word on Fire, a sub-committee of its board of directors engaged outside counsel, who engaged an investigator to explore the matter. One of the victims participated in the full investigation. The investigator provided findings to the law firm, who then worked with Word on Fire to communicate findings to the victims and to make decisions regarding Gloor’s employment. At least one of the victims was sent a letter from Word on Fire’s outside counsel on October 11, 2021, summarizing the investigation’s results and Word on Fire’s decisions at that time.

Two days later, on October 13, Bishop Barron convene a meeting with the Word on Fire staff. He discussed the investigation, Gloor’s eventual termination, and additional background. During this meeting, the role that “chastity” played in framing and addressing the issues was given some clarification. According to a transcript provided to me, the following is exchange between Bishop Barron and a member of the Word on Fire staff from that meeting:

Staff member: …I think, to me, the thing that comes out most clearly, is that Joe himself straight up admitted to a pattern of unchaste behavior while he was working in ministry at Word on Fire. And to me, that says everything. This isn't a, one lapse, and we need to forgive him. He was engaging in a pattern of behavior that was contrary to the Catholic faith, and contrary to what we were doing…

Barron: Yeah, no, I appreciate all that [name]. And we used that language throughout. We often had to explain it to the lawyer, what that means, to say someone is acting unchastely…

That is, it seems that Barron and Word on Fire had framed the work of their outside counsel with his team’s explanation of chastity. In addressing issues related to Gloor’s behavior, chastity seemed to have been the primary concern. And though the investigator explored the question of criminal behavior on the part of Gloor, chastity provides the key moral frame of reference here.

Additional context regarding the role of chastity can be found in the October 11 letter. The letter said: “Word on Fire determined a significant portion of the reported conduct is considered unchaste and sinful according to Catholic morality.” The letter also stated: “Mr. Gloor remains suspended while he undergoes compelled and intense direction from a third-party provider who specializes in working with Church leadership who manifest issues of unchastity.” (The attorney communicated that Gloor might return to work, and it was only after Word on Fire mistakenly believed the victim had shared her story in a public social media post that Gloor was terminated).

Hierarchies of sin

It’s important to note that the four women did not come forward to make allegations regarding consensual sexual behavior. According to one of the victims I spoke with, the women were alleging “sexual assault or abusive sexual behavior.” In the October 13 meeting, Bishop Barron also noted that the women had alleged “some kind of inappropriate or abusive sexual behavior.” The National Catholic Reporter has outlined some of this behavior, such as Gloor sexually exposing himself at the home of one of the victims without her consent. (The victim shared photographic evidence of this with the National Catholic Reporter and stated she had shared this evidence with Word on Fire.) Over the last few weeks, multiple women have reached out to me and shared experiences at Word on Fire that could legally constitute sexual harassment. But Word on Fire’s decided to establish “chastity” as the key moral category in addressing these issues. This diminished the problem by removing the connotation of violence from these experiences. And it enabled a confusion about which virtues and vices were relevant here.

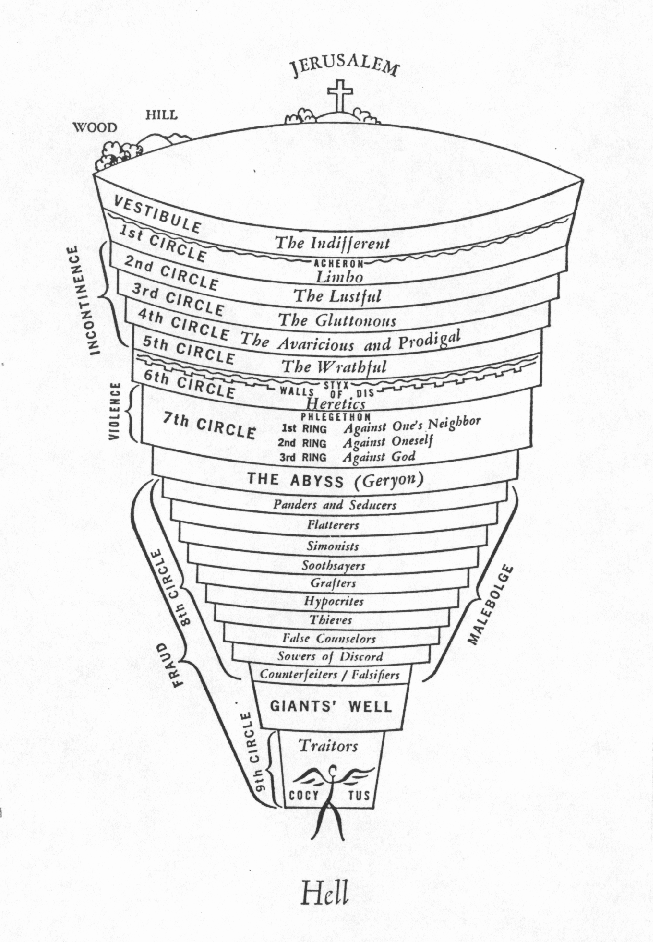

Dante depicts the hierarchy of virtues and vices in The Comedy. The journey into hell in Dante’s Inferno involves a descent through various “circles,” with each subsequent circle containing individuals who have committed increasingly serious sins. The second circle of hell depicted in Canto V includes a stormy windy dark place, where those who have committed sins of the flesh are swept about. Men and women move through the air like birds, but they are not really flying; they are simply being moved about by changing winds. This illustrates the life of lust: unable to control one’s passions, one is not really in possession of oneself and is driven about by unpredictable gusts of passion. This second circle is a place of lustful lovers.

Dante’s hell gets darker and more disturbing as one goes deeper towards the center. One meets more serious sinners in the circle of the gluttonous, and then still more serious sinners in the circle of the avaricious and prodigal. Then the heretics, and the violent, and the panderers and seducers, the flatterers, the simonists, diviners, and so on. In Dante’s hierarchy of vices and sins, lust is relatively innocuous compared to sins against, for example, justice. Lust is a vice. But, contrary to much Christian rhetoric today, lust is far removed from the center of hell when compared with sins like violence.

But it makes sense that certain Christian communities would want to treat chastity and lust as a more significant virtue and vice than justice and injustice. Under the hierarchies of much Christian praxis today, chastity becomes a higher virtue, in part, by making justice irrelevant. This plays an important role in enabling abuse, as I will discuss below.

What is sexual violence?

Psychological professionals frequently insist that sexual violence is not really about sexuality but is, instead, about control. But Christian communities continue to read issues like sexual harassment and sexual abuse through the lens of sexual desire and its moderating virtue, chastity. Thus, there tends to be a sharp contrast between how issues of sexual dominance, aggression, and violence are handled by Christian communities and the recommended approaches by the psychological community at large.

The approach taken by Christian communities, of treating issues of sexual violence as chastity issues, has significant implications. A focus on chastity when addressing sexual violence can often function both to distort the issues and to take focus away from the victims. If the maltreatment of women through sexual violence is an issue of justice, it is about a violation of the other, and not simply about one’s own sexual desires and behaviors. From a moral perspective, it is more akin to striking someone and less akin to masturbation.

When treated as a chastity issue, however, the maltreatment of women becomes less about the maltreatment of women and more about the struggles of the perpetrator. If we consider what justice requires for a woman attacked, we might consider how she might be healed, what might be required for a restorative process for her, how she might receive restitution and be treated as a hero for coming forward. But if we just consider what is required for a man who “struggled sexually” or was “unchaste,” we would focus on how he can be healed, and how he can change going forward; and we would operate under the belief that resolving such issues is sufficient to address the issues that the woman has raised. In the former, the woman is owed restitution and participation in the achievement of justice. In the latter, the focus tends to be on fixing or removing the perpetrator. Notice that in the latter scenario, the perpetrator might be put in a better position than he was previously (by receiving a training or support that betters him), while the woman’s position as victim remains untouched.

It may be that issues of sexual violence could include both issues of chastity and issues of justice. If that is the case, then both sets of issues ought to be addressed. The perpetrator ought to address his (or her) own issues of chastity. But the perpetrator, and the institutions that enabled him, must also address the issues of justice, the issues that would be most central to the experience of and impact to the victim.

A Disservice to Gloor

When Christian institutions fail to take this more holistic approach, they do a disservice to both the victim and the perpetrator. Consider Word on Fire’s decision to read Gloor’s behavior through the lens of chastity, and to require him to work with a “provider who specializes in working with Church leadership who manifest issues of unchastity.”

Word on Fire’s approach here (or, at least, my limited understanding of its approach based on documentation and background that has been made available to me) does not help Gloor recognize that he is an offender who has responsibilities towards victims. Instead, it risks encouraging a self-absorbed wallowing in his own internalized failings, ultimately helping no one, not even himself. He cannot say, “I’m sorry for having hurt you.” He can only say, “I’m sorry for being weak.” This is because he sees the issue through the lens of chastity, through a failure of his own integration, rather than through the lens of justice and violence in which he perpetrates harm that has an impact on another.

The focus on chastity is just a continuation of self-absorption. That’s one key problem with people obsessed with chastity: ultimately, this obsession is just self-obsession. In this way, a preoccupation with chastity can enable abusers. It takes their focus away from others’ experiences and inhibits them from recognizing others as victims. If this is just a violation against chastity, he has no responsibilities towards the women. The person he has primarily offended is… himself. The woman does not have a victim status. Only his own sexuality bears that status. This may be why perpetrators of sexual violence often reframe themselves as the primary victims when this violence is addressed.

Focusing on chastity can actually function to inhibit the perpetrator from becoming better. It can lock him in a vicious cycle, by convincing him that his issue is primarily with one particular vice, when in reality his issue arises primarily from another vice. This is consistent with approaches that focus on anger management when it comes to addressing, for example, domestic violence (as I’ve written on previously). Professionals have noticed that domestic violence is not primarily an issue of moderating anger. Rather, it tends to be an issue arising from “the need to control and gain power in a relationship,” where the abusive person feels entitled and harms the other when that entitlement is not fulfilled. What is needed is not simply for the abusive person to develop tools to better manage his anger, but a reimagining of what he is entitled to, along with a greater accountability to himself for himself (as opposed to expecting the other to moderate his desires and activities), true empathy for his partner, and an appreciation of the impact his actions has on others. He often needs to rework his view of what it means to be a man, and his expectations for women. An appreciation for the distinction between his own intentions and the impact he has on others is also key. He must learn to recognize that, for the victim, the impact of his actions carries much more weight than his intentions. And he must learn to be accountable for the impact of his actions, even when he has good intentions.

Addressing the issue of sexual moderation, without addressing these broader issues, will fail to get at the root of the problem, and will likely result in additional self-blame and partner-blaming when it doesn’t work. It may function to further entrench the perpetrator in harmful dispositions and dynamics, and set him on a journey doomed for failure. Institutions that seek to address these harms risk perpetuating and exacerbating them if they rely on misguided or misinformed solutions. Sending a perpetrator of sexual violence to a provider focused on “unchastity,” for example, will not suffice. Encouraging this focus does not help Gloor to change. It might encourage him to further entrench himself in problematic dispositions and behaviors.

Treating the issue as one of chastity can also function to limit duties of the institution in which the abuse occurs. It makes sense that a Christianity embedded within a highly individualistic culture would want to focus more on chastity than justice. A violation of chastity is much easier to treat as an individual sin, whereas a violation of justice is always, in some way, a social sin. Addressing only the former requires less of institutions. Ultimately, it is cheaper, easier, and more straightforward to address an employee and leader’s issues of chastity than it is to address an employee and leader who commits violence against others. An institution that promotes or enables a violator of chastity has no responsibilities towards victims (partly because, as was stated previously, victims disappear when the focus is on chastity). An institution that promotes or enables a violator of justice does have responsibilities towards them. Word on Fire does not see itself as having done anything wrong, in part because it sees the problem as solely a chastity issue that is isolated to Gloor and his personal life.

A revival of the clergy abuse crisis

Treating issues of sexual violence as issues of individual chastity also revives key problems from the clergy abuse crisis. It revives problems that were enabled by Catholic mental health professionals. And this raises a key question for me: who was the provider offering care to Gloor, and is there a connection here?

During the clergy abuse crisis, Catholic leaders saw the issue of clergy abuse primarily through the lens of chastity and through a simplified approach to trauma. Catholic conversion therapists such as Joseph Nicolosi and Richard Fitzgibbons were central in developing this approach. They established a narrative where the priest abused because he was suffering from a core wound (often from childhood) and an interaction with the child triggered the wound, causing him to abuse. They would recommend the priest be sent to a professional who could help “heal” the wound, and achieve sexual integration, after which the priest could be safely sent back into ministry. Responsibility for the abuse would be removed from the priest himself, and be placed on that “wound.” Thus, Courage founder John Harvey had argued that “priests who stray” (who abuse children) should be “rehabilitated,” writing that priests who abused should be viewed through the lens of addiction and that “sexual addiction reduced the imputability of many priests and religious involved in sexual acts with youth.”

This approach to abuse impacted victims in a number of ways. First, by focusing on the internal experience of the perpetrator, the victims were often not seen as victims. They were often not seen at all. They simply disappeared. They were lost to the focus on the “core wound” of the priest, such that the perpetrator would be seen as the primary victim. Second, the victims were often remade into perpetrators, as was the case with Benedict Groeschel in addressing the issue of clergy abuse. Catholic leaders such as Groeschel, often taking the cue of their selected Catholic mental health professionals, would view the children as seducers or as actors who would trigger the insecurities or wounds of priests, and thus the child would be the one causing the abuse. Victim-blaming was so common during the clergy abuse crisis, in part, because victim-blaming was a necessary part of the Church’s understanding of abuse. The objective actions of the priest were often lost to his subjective experiences, and victims were subject to additional harm.

This helped neither victims nor those who abused them nor the Church. For the victims, it left them forgotten, placed blame upon them, compounded harm, and worked against justice. For the perpetrators, it failed to address the actual issues at hand and put them in situations to further abuse. And for the Church, it turned our institutions into enablers of abuse, broke trust, and drove many away.

The way forward

I do think that things are getting better. Catholics have a better understanding of these issues. But maybe our leaders don’t. And maybe that’s part of the reason why Word on Fire has found itself in this situation. Word on Fire doesn’t seem to be combating the clergy abuse crisis. It may, instead, be helping to revive parts of it.

But the present situation does provide a learning opportunity for the Church. We cannot be reactive in our understanding and treatment of sexual violence or other forms of abuse. We must take advantage of best practices and proven methodologies in addressing these harms. And we must constantly keep our eyes on victims, who will help us understand what justice requires and how to recognize problems in the future. Our response to victims must not only be one of belief, but also of gratitude. They will help us change in ways we must change, if we let them.

More on this controversy:

Thank you so much for writing this.

Chris, some very important points here. However, I'm a bit thrown off by the title of your article. Don't you mean to say that a certain kind of "chastity culture" is what enables sexual violence in this way? Wouldn't the presence of true chastity, the virtue itself and people who strive to embody it, lead to the opposite of sexual violence, not to mention a sensitivity to and avoidance of the very errors you point out? Or am I missing something?

Maybe your wording is intentionally provocative, but I think there's something to be gained by making the distinction a bit more clear. I'd be the first to admit that there's some really messed-up "chastity" formation out there in both Catholic and Protestant/Evangelical circles. I'd even argue that we don't actually talk about anything more than a stereotype of chastity, most of the time. As a result, many of us can be tempted to completely dismiss it as a repressive, toxic ideal that's had its day and should be done away with. I fear some of your readers might draw this conclusion, in the absence of clarification.

I'd welcome a conversation about what an authentic, imperfect, graced engagement with the virtue of chastity really looks like for LGBTQ and hetero folks today.