To Win as Notre Dame

Notre Dame has a weird alma mater. You wouldn’t know that from a teleconference with head football coach Brian Kelly today. In it, he said that football players would not be expected to remain on the field and sing the school’s alma mater with the other students after home losses. He said:

“I just don’t think it’s appropriate to put your players after a defeat in a situation where they’re exposed… I want to get them in the locker room. It’s important to talk to them, and I just felt like in those situations, after a loss, there’s a lot of emotions. It’s important to get the team back into the locker room and get them under my guidance.”

The actions of his players didn’t coincide with his thoughts. According to the ESPN article, some players immediately left the field after this weekend’s loss to Oklahoma, but “most bee-lined toward the student section to engage in song.” Kelly clarified the “official policy,” however, that “we do not stay out on the field after the alma mater to sing after a loss.”

Now, my facebook feed is filled with infuriated statuses from Notre Dame students and alumni. But Kelly shouldn’t be the sole receiver of blame for this policy. It was the implicit decision of Notre Dame.

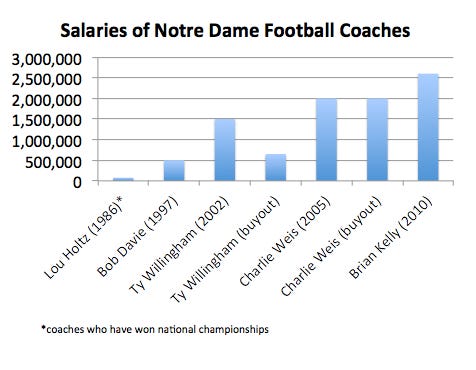

Consider this: In 1986, Lou Holtz was hired as head coach with a salary of about $75,000. At the time, a Sports Illustrated article noted: “the money really may not be that important; the football coaching job at Notre Dame isn’t something to be bargained over—it’s a prize, if tendered, to be accepted.” Holtz retired in 1996. At the time of his retirement, Notre Dame had thirteen national championships and an odd relation to its coaches. When Holtz’s successor, Bob Davie, was fired in 2001, the LA Times noted, “For all its football success, Notre Dame traditionally has not paid market price for coaches, although sources indicated over the weekend the school might be willing to pay the next coach $2 million a season.” Following George Leary’s brief tenure at as head coach at Notre Dame, Ty Willingham was hired with a salary of about $1.5 million.

When Willingham was fired in 2004, he became the “second-highest paid employee on Notre Dame’s payroll who is not an officer, director or trustee.” He was fired two years before his contract ended, and Notre Dame paid him about $650,000 for two years as a result. This is almost ten times the salary of Lou Holtz when he was head coach. This fact isn’t quite as shocking as his responses in an interview following his firing:

Q. Coach, what went wrong in your mind?

Willingham: We didn’t win football games. That’s it.

Q. What could you have done differently, if anything, to reach your expectations when you go back over it in your mind?

Willingham: There’s only one thing. Win. That’s it. That’s the bottom line. Win.

Still, when asked about the unique challenges of coaching at Notre Dame, Willingham responded: “What conditions are unique at Notre Dame? Gosh, Notre Dame is Notre Dame. There’s not another Notre Dame, so uniqueness is to itself, and that is a challenge, to exist and be what Notre Dame is.” The interviewer noted that “in announcing his firing, he was complimentary of the University, appreciated its ‘uniqueness’ and the challenges it presented – ‘a great place to be’.”

The firing was not received well by everyone, however. Professor Ralph McInerny of Notre Dame’s philosophy department penned an article in the New York Times, titled “The Firing Irish.” The following are some notable passages:

Concern with rankings began here with football, spread to other sports, and in recent years has been generalized, with academic standing as determined by various magazines and Web sites becoming an obsession. It seems to be received opinion that the success of our athletic teams is incompatible with Notre Dame’s refusal to regard athletes as more or less paid gladiators. We do not segregate our players in special “Animal House” -style residence halls, nor do we have bogus majors in which athletes are protected from the rigors of academic life…

A common assumption of much of the discussion of the Willingham affair is that Notre Dame has to accept the fact that good athletes are dumb, sometimes with ugly racist implications. Yet Ty Willingham played football, and no one could possibly think of this gracious man as intellectually handicapped. The same can be said of most of the students who, one is sometimes surprised to learn, are varsity athletes.

The point of an athletic contest is to win, but how one wins and loses is crucial for players and fans alike. The original idea of college sports was that games are a moral crucible that prepares one for life. The sad thing about the Willingham firing is that winning at all costs now seems paramount. Fans are by definition fanatic, but a university administration should take a longer view.

Current students and recent alumni will note the fact that most of what Dr. McInerny praises about the football program in 2004 is no longer true today. Although our players are not segregated in “special ‘Animal House’ -style residence halls,” residents of male dorms today will attest to the fact that athletic dorms aren’t required to create an on-campus “Animal House.” Dorm life at Notre Dame today is a long way away from a 1956 freshman’s experience in Zahm Hall: “Lights went out at 10, morning checks, ties and jackets for dinner, Saturday classes even on football weekends, no cars, strict rules on drinking.” One will also note the abnormally high concentration of high-profile athletes in certain majors (majors which I will not name here, but which every student knows).

After Willingham was fired and Kent Baer spent a brief time as interim head coach, Charlie Weiss was given a $2 million contract. Then, after he couldn’t give the school a winning record, his contract was cut short. By the time Notre Dame finishes its buyout, Weis may make up to $19 million from the University. Then, the “Notre Dame’s savior” rhetoric from Weis’ hiring began again with the hiring of Brian Kelly and a $2.6 million contract. With a nearly undefeated second season, many (perhaps most) considered the money to be well-spent.

And with that record, do students have a right to be angry about cutting the team’s participation in the alma mater after home losses? It depends on what you call a successful football program and what Notre Dame coaches are paid to do. According to Willingham’s understanding of his job at Notre Dame, “There’s only one thing. Win. That’s it.” So Notre Dame currently pays Kelly millions to win and pays Weis millions to do nothing. And eventually, I suspect, Kelly will join Weis, as a new coach is ushered in as the “savior” of the Notre Dame program.

So what does this have to do with my opening line, on how Notre Dame has a weird alma mater? I grew up in College Station, and I became quite familiar with Texas A&M’s alma mater, The Spirit of Aggieland. It sings of the school’s spirit, how “we are the Aggies… True to each other as Aggies can be.” It calls upon Aggies: “We’ve got to fight! We’ve got to fight for Maroon and White.” It seems appropriate following a football game.

But Notre Dame’s alma mater is softer, is slower, is reverent. It’s not even about the school. It reads:

Notre Dame, our Mother

Tender, strong and true

Proudly in the heavens

Gleams thy gold and blue

Glory’s mantle cloaks thee

Golden is thy fame

And our hearts forever

Praise thee Notre Dame

And our hearts forever

Love thee Notre Dame!

Notre Dame’s alma mater is neither a chant nor a cheer nor a victory hymn. It is a prayer honoring a woman, the University’s patroness and namesake.

This seems to be one fundamental thing that Coach Kelly doesn’t understand. The alma mater isn’t about us. It’s about Notre Dame. It’s about something greater than us. This perhaps can explain in part Lou Holtz’s odd comment before last year’s BCS championship game: “College football’s better when Notre Dame’s on top, where they are now.” Notre Dame isn’t better when it’s on top in the college football rankings; college football is better.

It’s almost comical to watch Lou Holtz provide commentary on Notre Dame football games. His treatment of the University may even appear to some to be a form of idolatry. He neither hides nor suppresses his bias towards the school. It almost seems that, to him, Notre Dame, win or lose, is the standard for college football.

I suspect this is because he, in fact, does think Notre Dame is the standard for college football. Or, to put it better, because the Notre Dame he knows has no standard but her own. He doesn’t prize Notre Dame because of her championship titles, although these certainly add to their glory. He prizes Notre Dame because she’s Notre Dame, and there could be no other. If Notre Dame is on top in football, it’s not a vindication of Notre Dame; it’s a vindication of football.

But the problem with this view is that it’s a view that is linked to the past and is decreasingly tied to the present. It is a view that praises Notre Dame because Notre Dame does things her way. It is a view that presupposes that if the standards differed between Notre Dame and the other schools, the other schools were surely failing. Notre Dame is only the standard when she sets the standard; if she accepts any other, she loses herself. The standard was once: Notre Dame is a Catholic institution; Notre Dame is an educational institution; Notre Dame has a football team.

I will not argue here the merits of Notre Dame’s identity as a Catholic institution, but I will consider one aspect of Notre Dame as a teaching institution.

It seems to me that Kelly’s decision regarding the alma mater exhibits a dangerous quality that the school has recently tended to fall into: the inability to teach its students how to lose. This seems to me a great disservice, especially for a university who’s religion is founded upon the death of its leader. Notre Dame students, including myself, are remarkably bad at failure. They have been taught only to succeed, a teaching that is evidenced by such things as grade inflation. But students have learned little if they have not learned that much of life is failure, and that one must usually fail many times before one succeeds. Failing itself does not make one a failure. Rather, one’s response to failure is often the measure of a man. The successful man is not simply the man who succeeds; it is the man who succeeds rightly.

This is the lesson that Notre Dame football in recent years has sought to eradicate from Notre Dame’s curriculum. The lesson is now: “There’s only one thing. Win. That’s it.” If you’re not winning, recruit differently. Fire the coach. Cut the prayer.