The Catholic Studies reckoning we never had

I’m writing this partly because I feel some guilt over going to the gala this weekend.

CW: discussion of clergy sexual abuse of minors.

The narrative we told each other—and ourselves—was this: she was making these accusations because she was mentally unwell.

1. Defenders of the Faith

In September of 2013, former chancellor of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Jennifer Haselberger went public with allegations that the Archdiocese had mishandled clergy sex abuse cases for years. In response, the Saint Paul police reopened a previous investigation into one of the accused priests. This was just the beginning of our journey as a community, a journey which would lead to a ballooning scandal, an Archbishop’s resignation, and Archdiocesan bankruptcy. But we didn’t know any of this was coming in September of 2013.

A few weeks after Haselberger’s explosive story went public, the Department of Catholic Studies at the University of St. Thomas was grappling with accusations in its own tight-knit community. I was in my first year of the Masters in Catholic Studies program. We students knew very little at the time, and Catholic Studies was telling us basically nothing. Father Keating, one of the department’s most popular and charismatic professors, had gone on leave. Rumors circulated as we became aware of a lawsuit filed a few days after. Keating was accused of sexually abusing a child more than a decade ago, while he was a seminarian. “The story” circulating among Catholic Studies students was that she had misremembered and was lashing out against our revered Catholic professor because of her mental instability.

The University of St. Thomas issued a public statement from its President Julie Sullivan. She acknowledged Keating’s leave of absence, notified everyone that the University would be reviewing the situation, and reiterated the University’s zero tolerance policy for abuse.

A couple of weeks later, I had a dinner with Archbishop John Neinstedt and a handful of guys in Catholic Studies. At the time I, like the other guys, admired Neinstedt. We saw him as a bastion of Catholic orthodoxy in a broader culture we viewed as hostile towards the Church. We talked briefly about Haselberger. Commenting on the lawsuits against the Archdiocese over abuse, Neinstedt said that some people are just out to get the Church.

As news continued to break about the Keating lawsuit, an email circulated within the Catholic Studies community from one of its graduates, a law student at the time. It encouraged us to take heart and assured us that Father Keating was doing well. It emphasized his virtues as a man and a priest. The email gave an overview of then-available facts, some information on legal nuances in and procedures for the case, and reassurance that Keating had hired an excellent attorney. It emphasized how “we know Fr. Keating.”

Because I was a law student myself (I was getting a joint J.D. and M.A. in Catholic Studies), friends in Catholic Studies went to me for opinions. In response to a press conference given by the plaintiff’s attorney on the Keating case, I wrote to one of them:

“I had seen that. My recommendation is to not think much of it. And my very sincere recommendation is to not follow this in the news. I've heard that Jeff Anderson (the attorney) is known for being sensationalistic and for seeking a lot of public attention. I don't think he is being fair to the process that the archdiocese undertook to do the investigation. The archdiocese not only undertook its own investigation, but the Chisago County Sheriff's Department also undertook its own criminal investigation and found that there was insufficient evidence. That's why Anderson didn't file a criminal complaint: he can't support his claims with enough evidence…

“Don't let this tarnish the good experiences you've had and the good things you've learned. And don't let this tarnish the love and respect you have for a truly great man. Regardless of whether the allegations are true or false, we do know that he is a sinner, like all of us, and that past sins do not prevent one from becoming or being a saint.”

Among the students, the sources of information were: the media, each other, and what other students were hearing around or from Keating himself.

Searching through my emails now, I’ve been unable to find any communications directly from Catholic Studies to us students on the matter. This surprises me. We had studied under, received direction from, and (for many in the study abroad program) lived with Keating. As the lawsuit continued on, some of us, unaware of any need to exercise caution or take the allegations with any degree of seriousness, continued to meet with Keating for group dinners or other activities. (I only attended one, though I would have attended others if I’d received invitations.)

We didn’t know of any Archdiocesan or other restrictions regarding Keating’s activities. We also didn’t know that our department’s leadership knew much more than they were telling us.

A year later, in October 2014, the University concluded its investigation. Though the results remained confidential, President Sullivan shared some findings. Neither she, the University president preceding her, nor any of their current or former direct reports were previously aware of the allegations against Keating, which had come to the Archdiocese years before the lawsuit. They had also not been aware of any Clergy Review Board restrictions on Keating’s activities. And the university had not received any prior complaints of sexual misconduct against Keating. Keating continued to deny all allegations.

2. Discoveries

As the years passed, I changed. After learning more, many Catholic Studies alumni came to view the Keating case very differently. As we grew up, the victim in the lawsuit became much more credible to us. We learned more about abuse generally. And we learned about the extent of our Archdiocese’s failures to respond to abuse and protect victims. But there were key facts I still didn’t know.

In June of this year, 2023, I spent a weekend watching Shiny Happy People and The Secrets of Hillsong. By coincidence, I was also doing research on conversion therapy and Catholic professionals and came across a document with a timeline of the Keating case. Below are some of the details from that document (supplemented by other documents, linked where added):

The victim in the lawsuit alleged multiple instances of sexual abuse by Keating when he was in seminary. She was 13-15 at the time and he was in his forties. The victim saw a psychologist in 2006, who said she suffers classic symptoms of having been sexually abused. In a series of email messages Keating sent to the girl during that time, he told her things such as “Be really sure that I love you lots and lots and never think of you without a smile coming to my mind,” and “I’m afraid you are going to have to get used to being hounded by boys,” and, “You’re too pretty and too charming not to be and you’ll only get prettier and charmier as the years go by.” He addressed her as “Dear Sweatheart” and ended one email with “a kiss and a hug.”

By 2006, the document states, Keating had admitted to Archdiocesan officials having had a “passionate physical encounter” with an Italian girl while he was a seminarian. He said she had seduced him. The girl was 15-16 at the time and Keating was 43-44.

Also in 2006, McDonough (then Chancellor and Vicar General for the Archdiocese) wrote in a memo to Archbishop Flynn and other Archdiocesan officials of problems related to Keating: "That issue concerns an ongoing pattern of irresponsible seductiveness (non-sexual) in Father Keating's life."

In January 2006, a priest reported to the Archdiocese abuse allegations against Keating. A memo was sent to Archbishop Flynn the following month…

“summarizing Keating investigation. 1) Keating involved with [redacted] in a relationship she found ‘deeply confusing.’ Keating unaware of the inappropriateness. 2) Keating involved with young daughter of [redacted]. She recalled at least one occasion that may have constituted sexual abuse. Reported or about to be reported to Chisago County. 3) Keating engaged in emotionally intense and perhaps physically sexual relationships with 2 other under aged young women—1 lives in Italy and the other is someone whose family Keating lived with 15 years ago. Many people commented on one of the relationships, which included public kisses.”

In May of 2006, Fr. Peter Laird emailed Fr. Andrew Cozzens, stating that he had seen Keating dressed in lay clothes in Rome…

“sitting arm and arm with a younger woman - perhaps college age… Laird found this odd. Laird called Keating on it, saying it was not appropriate or prudent. Keating’s reaction led Laird to believe he is manipulative or naïve.”

In 2007, the Archdiocesan Clergy Review Board determined there was insufficient evidence for a finding of sexual abuse of minor, but outlined restrictions, given the impact of Keating’s relationships with multiple young women. This included that Keating not engage in retreats, counseling or mentoring of adolescents or young adults.

A 2008 memo from Father Kevin McDonough to Archbishop Flynn stated that they should meet with Dr. Briel to inform him of the investigation and its conclusion.

In 2008, Archbishop Nienstedt was made aware that Keating was still providing spiritual direction, was overseeing events at the Catholic Studies’ Women’s house, and was not under monitoring. (Nienstedt had taken over leadership from Flynn that year.) He was not aware Keating was not being monitored.

In May 2010, a memo from Vicar General Fr. Lee Piche confirmed no monitoring program had been put in place.

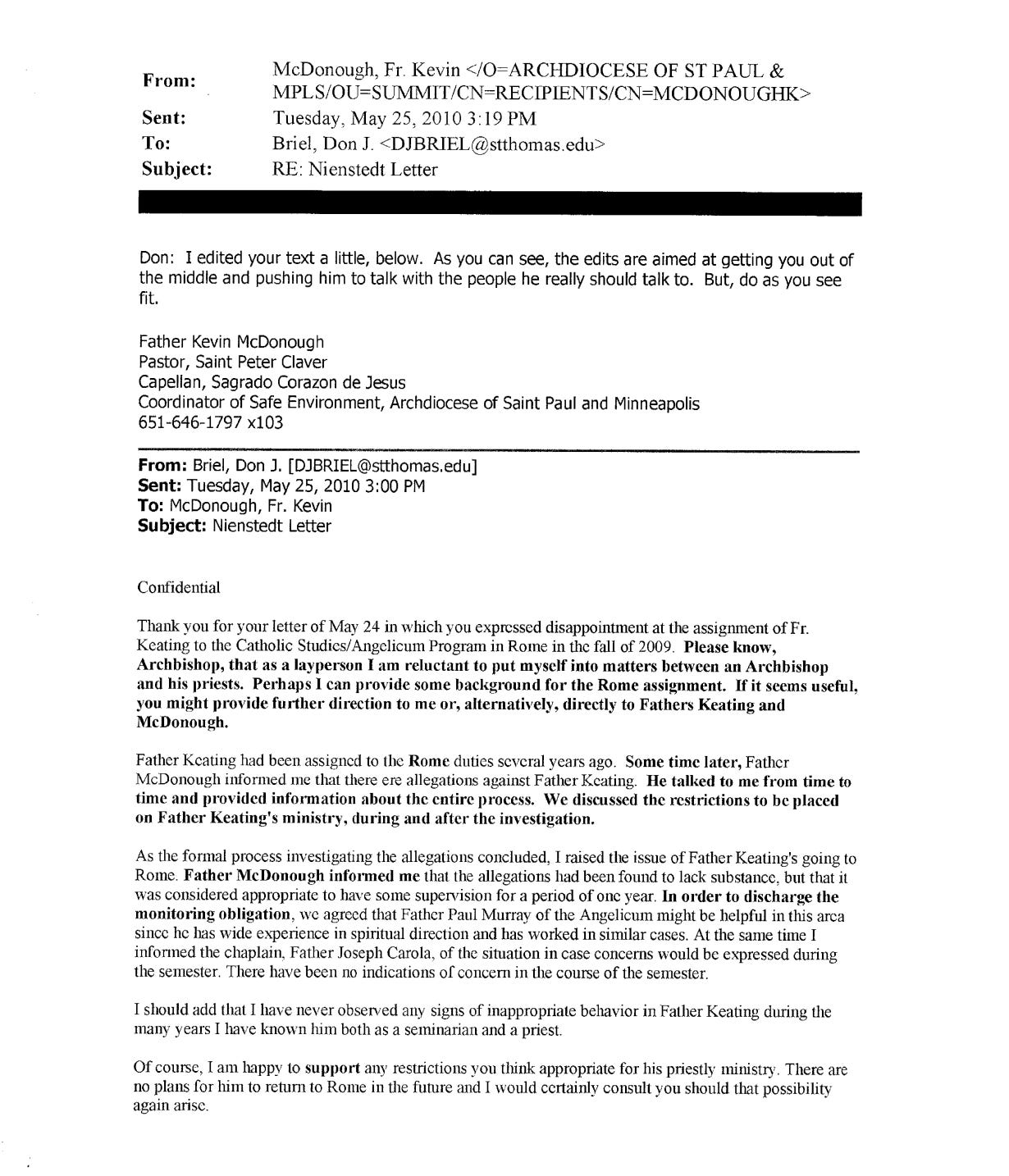

Also in May 2010, Nienstedt sent a letter to Briel. It included the following:

“I wanted to put in writing the disappointment I felt in the assignment of Father Michael Keating to the Catholic Studies Program in Rome this past semester. As you know, there have been some acquisitions (sic) against Father with regard to his relationship with young women. I think that it was unfortunate that he was allowed to be away from the University campus, even though he did have some minimal supervision in Rome. I am writing with the hope that we would not repeat this kind of an assignment for Father in the future. He needs to be home where his activities can be monitored.”

A couple months later, another letter confirmed that Keating would sign a monitoring agreement, but Keating reiterated he was not involved in sexual misconduct.

In 2012, Nienstedt sent a letter to Keating, surprised he was accepted as a Trustee on the Board of the University of Mary without consulting him. Nienstedt stated that Keating should inform them of the allegations against him to prevent future scandal. (The Archdiocese sent a letter to inform the University of Mary.)

2012: Email from McDonough to Fr. Shea of the University of Mary…

“discussing Keating’s standing in the Archdiocese at Nienstedt’s request: 1) Keating is in good standing in the AD; 2) years ago parents of a family close with Keating expressed concerns- daughter was 15, he was physically and emotionally close to her, over time her ‘recollections’ became more intense and abusive; 3) law enforcement contacted; no charges brought; 4) Review board thought he was still fit for ministry; 5) All was disclosed to UST president and the director of Catholic Studies. In his opinion, the daughter was suffering from mental and/or emotional disability and ‘delusions’ at the time.”

The following year, in 2013, the lawsuit against Keating and its public coverage would precipitate Keating’s leave of absence from Catholic Studies at the University of St. Thomas. When MPR reached out to Dr. Briel in 2013 as part of a story, Briel would not say whether he had previously known about the allegations against Keating. Briel retired from the University of St. Thomas in 2014, and soon after received an honorary doctorate from the University of Mary and took on the role of its Blessed John Henry Newman Chair of Liberal Arts. The Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis faced both civil and criminal lawsuits over its mishandling of clergy abuse cases. By the end of 2015, all of the Archdiocesan leaders named above—with the exception of Fr. Cozzens—had left their leadership positions, and the Archdiocese had filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy.

3. Seesaw

Watching Shiny Happy People and The Secrets of Hillsong while learning about these details of the Keating case impacted me in at least two ways.

First, I remembered how Keating made me feel. Keating was a man who always had an “in group” and an “out group.” In 2006, Keating began the “Catholic Studies Leadership Interns” program, in which he selected a group of Catholic Studies students to participate in a set of exclusive activities, including a trip with him, sometimes to Chicago and sometimes abroad. The exclusivity and aura bestowed on those selected for the internship was so pronounced that other students jokingly referred to themselves as the “Catholic Studies externs.” To be selected by Keating made you special. When you were “in,” you felt something. When you were “out,” you felt something too.

I wasn’t above this. I still remember the way Keating made me feel when I sensed that he thought something I said was intelligent. It’s a hard feeling to describe. It’s like he was this celebrity on another plane, and when he saw you, he was bringing you up into that plane as well. Once you’d known the feeling of being there, you wanted to get there again and stay there. Only he could get you to that precise place.

Some students were jokingly referred to as “Keating-ites.” They took on his mannerisms and ways of speaking. There are still certain hand gestures I associate with Keating, and which I had adopted myself. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Newman says that teaching involves more than just the dissemination of information; it involves the passing of life from teacher to student. But this passing isn’t always safe, and educators haven’t always done a good job of noting the dangers of this sort of activity. This passage opens many doors to the self, something which has contributed to teacher-student scandals across educational institutions over the years, even from the time of Socrates.

Watching The Secrets of Hillsong and hearing people describe the way Carl Lenz made them feel, I started to recognize this in my own relationship with Keating, even though I was not nearly as close to him as other students. To be seen by Keating made you smart, worthy, special. To not be seen by him just made you an “extern.”

I now see that the communal psychological conditions had been created under which abuse, in various forms, could easily occur and then be maintained. I’m not sure that Keating was aware of the ways in which he had fostered these conditions. But neither was Carl Lenz.

Second, I felt rage. But it wasn’t rage at Keating. It was anger at Don Briel and the Department of Catholic Studies.

I realized that Briel was aware of the accusations against Keating concerning his relationships with young women in the past, and he had still sent Keating to live with young women in another country as part of the Catholic Studies program. He took a risk on those young women, without given them (or their parents) an opportunity to consent to the dangers.

I think: How would I feel if I were a parent of one of the young women in Catholic Studies, and I found out the department chair had been communicated restrictions for a priest-professor due to multiple allegations of inappropriate sexual and emotional relationships with significantly younger women, and that chair still decided to send that priest to live in another country—living in the same residence—with my daughter? The University should be an alma mater, a nourishing mother. What responsible mother would go along with this? Mine wouldn’t. Note how none of the people involved in these decisions were parents. They were all single men in positions of ecclesial power.

I know some of these women that Catholic Studies put at risk. I was furious. I still don’t know exactly how to write about this because of the anger this brings up in me. I thank God that I am aware of no instances of alleged or rumored abuse or manipulation by Keating against any Catholic Studies students. I pray to God that there aren’t any. But if there were, why would they want to come forward, when they’d already seen our community implicitly rally around Keating and dismiss his alleged victim as deluded and emotionally unstable?

In fairness to Briel, he had sought to follow some of the restrictions. This can be seen in a draft of Briel’s response to Nienstedt’s 2010 letter. As part of the monitoring process while Keating was in Rome, Briel wrote that he believed Father Paul Murray, a theologian teaching at Rome’s Angelicum, might be “helpful” because of his “wide experience in spiritual direction” and work in “similar cases.” It is unclear how such experience might be helpful in protecting students abroad. Briel also informed the Rome program’s chaplain. But, notably, it seems he did not inform the program’s campus director, the only member of the St. Thomas staff who would be living in the residence with students along with Keating. This is a striking omission. And, if President Sullivan’s statements are to be believed, it seems that Briel made these decisions without informing or consulting with Unversity leadership. (Documents released over the course of the lawsuit would put in question whether the former President, Father Dennis Dease, was really unaware of the allegations and restrictions.)

In any event, Briel’s message to the Archbishop, co-written with the Archdiocese’s Coordinator of Safe Environment, demonstrates a lack of investment in digging into the matter before sending an accused priest to live with students abroad. Briel writes, “I am reluctant to put myself into matters between an Archbishop and his priests.” This is a shocking lack of responsibility for a man participating in decisions about students’ living arrangements in another country. Briel is implicitly communicating a couple of things in this letter: he doesn’t take the allegations seriously, and he’s not really interested in learning more.

The lack of new allegations doesn’t excuse the fact that the founder and leader of the program chose to take that risk with my friends. If Keating had abused or manipulated my friends, I’d certainly hold him responsible. But, in many ways, I would hold the Department of Catholic Studies even more responsible.

As a Church, we teach our abusers how to behave. We teach them the bounds of accountability. We teach them the lines they are allowed to cross before we will pay attention, and we teach them whether consequences are real or not.

The Department of Catholic Studies taught Father Keating that, when it comes to protocols for a priest accused of abuse, one need only do the bare minimum to protect other vulnerable young people. It taught my friends that we do not need to concern ourselves with the past allegations against Keating, some of which he admitted to. It taught that charisma and intellectual prowess can “get you a pass” at times. It taught me that you can risk the safety of young people, and it doesn’t matter as long as nothing happens. Or, hopefully, no one finds out for a long time, after the victim has had a mental breakdown, after which you can label them as “delusional.” It taught that, when your friend is accused, anchor in your own relationship with them and learn as little as you need to about the situation. Keating denied he engaged in any “sexual misconduct,” he continued to say that he did nothing wrong, that he was “seduced,” that he was the one wronged, partly because we all taught him to say that.

Institutionally, Catholic Studies was teaching us all how to behave, and demonstrating the very behaviors that led to our Archdiocesan bankruptcy.

These lessons continued, even after the departure of Briel. Over time, the open secret of dinners with Keating transitioned to the open secret of ghost writing. Catholic Studies continued on as if the Keating issues were just some oddity of history to be forgotten. I attended department events. Some alumni shared with me how the work of Keating continued, via ghost writing he was doing for a number of publications being released by a Catholic Studies partner program and featured at the Catholic Studies events I was attending. We all continued to try to bask in the brilliance of that charismatic and highly intelligent man. At the time, I felt glad that Keating’s brilliance wasn’t being wasted, and I also felt a little uncomfortable.

Now I mostly feel uncomfortable, among other things.

At this moment, I feel that my relationship to Catholic Studies is in a bit of a seesaw stage. I process, with horror and fury, the lackluster interest in and compliance with restrictions placed on this priest, the risks taken with my friends, and the lack of acknowledgment of any any of this. And then I get together with old classmates and professors and rekindle the warmth of our time in the program and feel the love we have for each other. I think about the grief and trauma I have had to process because of how Catholic Studies treated me (more on that later). And then I think about the important lessons it taught me about life and which continue to serve me today, including serving my ability to write this piece. I think about the lessons Keating taught me and which I still value and have some kind of gratitude for. And then I think about the lessons Catholic Studies taught me about discrediting victims as Keating’s case became public, and I feel shame.

There must be a way to hold all these things together: the love and the fury, the good we cherished and the bad we are now coming to see, the formation of leaders and the failure of leadership.

4. Leader

I so badly want the Church to be a light to the nations. But I worry about the tendency in the Church to shine the light everywhere except on ourselves. To lead as a Church in 2023, to truly lead, means to lead in a way that gives some centrality to the clergy abuse crisis. Leading by example means doing differently than the Church of prior decades.

What concerns me is that, when it comes to Catholic Studies, nothing was really any different. Institutionally, we avoided the issue. We avoided restrictions. We maligned the victim. We celebrated everyone implicated, as much as we could. For the individual most directly implicated, once we couldn’t comfortably deny the allegations publicly, we kind of just avoided his name and continued to give him as much access as we could. Afterwards, we didn’t talk about it. Everyone moved on, except for the victims and their loved ones.

And me.

And I hope others.

Given the clergy abuse crisis, we as a Church need new paradigms for many things. We need a new paradigm for leadership, one which says sorry for something, literally anything, when we fail to protect the vulnerable. We need a new paradigm for truth, one in which the “hard truths” to be told are not just unpopular sexual teachings but are the ugly things that we have ourselves been a part of. We need a new paradigm for community, one which finds ways to create belonging for the people on the margins, the people who do not feel welcome because of the ways in which we try to push their pain as far away from us as possible, especially when we or those we love have contributed to that pain. What would it mean for Catholic Studies to build itself as an institution that the women who came forward with the allegations against Keating would feel proud of, would want to be a part of, would feel like its halls are their halls and like its teachings will help others like them?

When it comes to seeing these things, I think I’m in a privileged position among Catholic Studies graduates. I too am an outsider to Catholic Studies (though to a lesser degree than those women). As an outsider, I have the privilege of getting to see some of these things more clearly.

One way in which I’m an outsider: During my time in the program, I was asked to take on an internship working for the Holy See at the UN. But after I shared that I had spoken publicly about being a gay Catholic (in order to defend and promote Church teaching), Dr. Briel told me it would “not be a good time” for a gay person to take the position. The Department of Catholic Studies told me: we “cannot think of a better candidate… than yourself” (they literally used those words), except… that you’re gay.

Gay students need not apply. I look back, and I still feel that I was told that I was good enough for that position in every way, except for this one shameful part of myself that ruined everything. So I would never be good enough. And nothing I could ever do could ever change that.

I wrote about all this publicly. It circulated throughout the department, but I’m not sure who exactly saw it. One professor who had no involvement in the situation emailed me to apologize. But that was it. In that piece, I detailed the pain I continue to feel in the face of blatant discrimination in violation of the Catechism, and the department did and said nothing. And continues to do and say nothing. I don’t really belong there. I don’t really belong in this Church. But I keep showing up. People keep asking me why.

I worry that, for Catholic Studies, leadership is primarily conceptual. It’s something we theorize about, but we don’t need to demonstrate it in practice, as long as the theory is compelling. I think this is partly why Briel and Keating may be key leaders for Catholic Studies: what we found most compelling in them were the concepts they conjured, which we loved in lieu of seeing the actual complicated histories of these men. This is why Catholic Studies can host events on the clergy abuse crisis and talk about how others need to talk about it, but we never talk about our own institutional relationship to it.

5. Extern and Intern

I think: Catholic Studies isn’t for me.

But I remember that I am Catholic Studies, too. I think. I am an alumnus. Even if I was never going to get an equal chance at opportunity, I have the degree. I will be going to the Catholic Studies gala this weekend.

If I’m being honest, I’m writing this partly because I feel some guilt over going to the gala, and I hope that just getting this out in the air can help me to engage more deeply with the reality of Catholic Studies as I attend. But maybe I’m just trying to justify to myself the decision to attend? In any event, I felt that I couldn’t go unless I wrote this. That was the message, the vocational demand (God?), that I couldn’t escape.

I am out. But I am also in. Extern. And, in some ways, intern. So I have a role to play, I think. There is much more to say and to do. If I want Catholic Studies to begin this, I guess I can begin. And I can invite others to do the same. If we are doing it, then Catholic Studies is doing it… right? And, sure, I don’t have the funding or reach or visibility of the Department. I’m just a guy with a glorified blog. But that still counts for something, right?

I still struggle with the Keating case. I continue to feel admiration for Keating’s charisma and intellect. I still value many of the lessons he taught me. I’m sure I’d still hang on every word at some dinner table with him. I’m sure I’d learn a lot and be grateful for that. But I’ve also come to recognize how these two things, charisma and intellect, can be the primary tools of the self-deluded, especially the self-deluded who spread delusion into their communities. To the extent Keating may be an aspiration for some, he is also a cautionary tale.

The tale is partly about the limits of the Catholic pursuit of Truth. Catholic institutions that pursue the big “Truths” will become parties to the dynamics of abuse if we do not come to take accountability for the many smaller truths in which we take part. We cannot use the grand narratives of Catholic history as cover under which to hide the particular truths of our personal histories. I have done this, and that way of living is a way of death.

Some will say: “You shouldn’t be writing about this. You don’t have the whole story.” It’s a tired response, really. It’s one that comes up every time abuse is discussed in the Church, whether it’s McCarrick or Maciel or Weymeyer or Keating. Sure. I don’t have the whole story. If those in possession of the particulars wanted to give the whole story—or, at least, more of the story—they can. But they cannot hold these particulars as clubs with which to beat into silence others who are suffering. One’s choice not to speak does not justify shaming and silencing those who are earnestly struggling for the truth, especially when that struggle is in the name of seeking accountability, protecting others, or pursuing healing. It’s important that Minnesota Public Radio titled their documentary on our Archdiocese’s abuse scandals: “Betrayed by Silence.” I don’t want to participate in that betrayal.

Some will say I am writing this as a disgruntled alumnus, as someone who is “out to get” the Church and the Department. Two sides are presented: the side of the Archbishop at that dinner table many years ago who anchored in the people “out to get” us, and the side of the young woman who was abused by one of our leaders and had to struggle through agony to find her voice. If I have to choose a side, I will chose the latter. That side seems to me to be the side that gives a chance at real love for the Church and the Department. I’m tired of a Church that drives itself to bankruptcy, both financial and moral.

I am a disgruntled alumnus. And I’m an alumnus who longs so deeply for a Department and a Church for which I can feel deep pride. If I didn’t care, I would have “moved on.” If we want Beauty, we have to travel a path with a lot of ugliness. I believe it is possible to love these institutions and people, and also fully acknowledge and process and shed light on the ugliness they—and we—have held or created or perpetuated. This seems to me an essential part of living the “truth in love,” especially today.

Catholic Studies is often marketed as a program where students enter and receive formation to go out and transform every aspect of our culture. The culture needs transformation. So does Catholic Studies. I think many of us needed formation in Catholic Studies, and then formation in the broader culture, so that we could come back and transform the place we came from. We are called to make what we once saw as home into a true home, for ourselves and others.

Like all of the culture, Catholic Studies needs renewal. I write this, not because I believe Catholic Studies must be broken down, but because I believe—I hope—Catholic Studies has the capacity for renewal. If I, a sinner and a failure and a deeply broken person, can be renewed, then surely this community, full of brilliant and caring and good people that I find myself loving and admiring and wanting to be close too even with all of this, can be renewed as well.

And so it’s time for me, as a member of Catholic Studies—in and out, intern and extern—to take accountability myself.

Here’s some accountability from Catholic Studies, from me: I participated in these dynamics of abuse as the allegations against Keating were becoming public. I spun the protective narratives for Catholic Studies. I played it safe to save face. I didn’t talk about these things. I chose the simplicity—the complicity—of silence over the complexity of reality.

This piece is an attempt to do differently, and an invitation to others to do the same.

Wow. Taking a step back, why is “let’s keep this guy in active ministry but not leave him alone around young women” even an option?

A guy like that who was a random youth group member would get banned from the youth group. But if you’re the priest running the youth group...