Scandal, the Abuse Crisis, and Unmarried Pregnant Women in Catholic Schools

The Church has not sufficiently considered the extent to which a misguided treatment of “scandal” contributes to other crises.

The concept of scandal is key to making sense of the clergy abuse crisis. It played a fundamental role in the building and maintenance of the crisis. But scandal has not been seriously considered when it comes to responding to the crisis. And the Church has not sufficiently considered the extent to which a misguided treatment of “scandal” contributes to other crises.

When it comes to the clergy abuse crisis, and especially the particular crisis of the cover-up of the sexual abuse of children, scandal has played a central role. In its 2004 report on the crisis, the National Review Board for the Protection of Children and Young People (NRB) listed seven key shortcomings on the part of Church leaders. The fourth shortcoming was: “reliance on secrecy and an undue emphasis on the avoidance of scandal.” The NRB wrote:

“Faced with serious and potentially inflammatory abuses, Church leaders placed too great an emphasis on the avoidance of scandal in order to protect the reputation of the Church, which ultimately bred far greater scandal and reputational injury. One bishop opined that because the Church in the United States historically is a minority, immigrant institution, it has been particularly desirous of seeking to solve its own problems without exposing them to a hostile culture. Several others echoed this thought. This desire to keep problems ‘within the family’ also may have stemmed from a shortsighted concern that the faith of the laity would be shaken by their exposure.”

The impulse to avoid scandal, according to the NRB, manifested itself in a number of ways, including in a lack of candor on the part of Church leaders, the withholding of information, and pressuring those affected by the abuse to be silent. This resulted in failures to report harmful activity, the marginalization of victims, and the inability to adequately respond to the crisis. The NRB saw misguided concerns about “scandal” to be central to the crisis.

What is scandal?

But what is “scandal” in the Catholic tradition? And, given what we know about the abuse crisis, how might we treat it differently?

Scandal might be considered the vice in opposition to the virtue of charity. In his Summa Theologiae (II-II:43), Thomas Aquinas defines scandal as “something less rightly done or said, that occasions another’s spiritual downfall.” A couple of things must occur in order for something to constitute a “scandal properly so called.” First, the thing “done or said” must be an evil itself, or have “an appearance of evil.” Aquinas gives the example of a man sitting to eat in the temple of an idol, which is not sinful itself but might give the appearance of idol worship. Second, the thing done or said must dispose another to sin. The word or deed involved is not the cause of another’s sin, since, according to Aquinas, only one’s own will can be a sufficient cause of one’s sin. Instead, the word or deed is the “occasion” of another’s downfall.

According to Aquinas, there are two types of scandal: passive scandal and active scandal. Passive scandal is a sin in the person scandalized when that person has succumbed to sin. Passive scandal may occur on the part of the person occasioning the scandal as well. However, that person would not be committing a sin if, for example, they do a good deed that results in another being scandalized. On the other hand, active scandal occurs when one acts with the intention to lead another into sin, and this is always a sin in the person giving scandal. Aquinas says this is always a sin, because (1) the act itself (with the intention to harm another) was itself a sin, or because (2) the thing which had the appearance of sin (but was not necessarily a sin in itself) should not have been done out of love of neighbor, and was thus an act against charity.

Aquinas questions how far we should go to avoid occasioning scandal, in terms of foregoing spiritual or temporal goods. And here he makes a distinction between scandal that arises from weakness or ignorance, and scandal that arises from malice (such as “‘the scandal of the Pharisees, ‘who were scandalized at Our Lord’s teaching”). Aquinas says that we should never forego the spiritual goods necessary for salvation. But when it comes to scandal arising from weakness or ignorance, Aquinas said we ought to conceal or defer other spiritual goods, as well as temporal goods, until there is an explanation that would cease the scandal or the scandal is abated by some other means (such as an admonition). When it comes to scandal arising from malice, Aquinas says we should not forego either spiritual goods or temporal goods.

What’s particularly important to note in Aquinas’s discussion of avoiding scandal is his argument that scandal can cease by being explained or being abated (through things like admonitions). Aquinas says that if scandal continues to be experienced after an explanation, then the person’s experience of scandal “would seem to be due to malice,” and this should be treated “with contempt” like scandal of the Pharisees. Likewise, in its “Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services,” the USCCB considers “collaborative medical arrangements that entail material cooperation in wrongdoing” and says that in some cases, “the risk of scandal can be appropriately mitigated or removed by an explanation of what is in fact being done by the health care organization under Catholic auspices.” In his handbook on moral theology, Dominic Prummer also notes that one is not always obligated to avoid scandal. Prummer notes, “For a just cause it is lawful to permit and even to provide the occasion of another’s sin. In such circumstances the neighbor’s sin is not intended, and even God himself permits the occasions of sin.”

It's also important to note here the role of vulnerability. Scandal occurs because one has influence over another. There is the influencing party (the one speaking or acting to cause the scandal) and the vulnerable party (the one who is influenced to commit sin).

Scandal and the Abuse Crisis

Church leaders were concerned about “scandal” related to the release of information about abuser-priests. It is not clear, however, what “sin” on the part of the laity they were seeking to avoid. One might argue that they were seeking to avoid a situation which could harm the reputation of the Church and thus lead people away from the Church. But in making such a calculation, Church leaders seemed to not understand the laity, and especially the abused. The NRB report included a statement by one bishop:

“We made terrible mistakes. Because the attorneys said over and over ‘Don't talk to the victims, don't go near them,’ and here they were victims. I heard victims say ‘We would not have taken it to [plaintiffs' attorneys] had someone just come to us and said, ‘I'm sorry.’’ But we listened to the attorneys.”

Here, a commitment to a rehabilitation of the victims and increased transparency might have supported the reputation of the Church. In addition, it would have encouraged the laity to view the clergy as more human and, thus, would have helped to resist the undue deference to clergy that helped support the crisis. Instead, an overly defensive posture became the real scandal, ruining the Church’s reputation, driving devastating lawsuits, and preventing a look at the real scope and nature of the crisis. The abuse crisis was not driven by an avoidance of scandal, but by a misguided treatment of scandal.

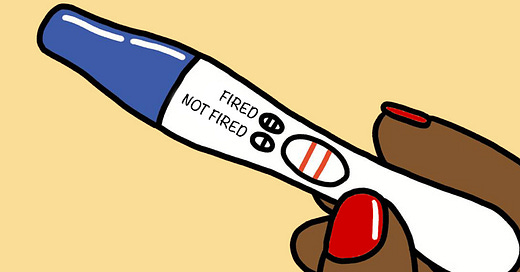

Unmarried and Pregnant

A look at another issue might help to further clarify ways in which the Church could better approach the question of “scandal.” In June of last year, the New York Times covered the story of an unmarried Catholic school teacher who was fired “because she was pregnant and unmarried.” The teacher sued. The teacher’s attorney argued that because the school’s only proof of a violation of its morals code was the pregnancy itself, “only a woman could be punished, not a man.” The attorney clarified that he does not see the lawsuit as an attack on the Catholic Church. In response, the archdiocese which oversees the school framed the lawsuit as a fight for the “fundamental freedom of religion.” Lawyers for the school argued, “Sex outside of wedlock violates a fundamental Catholic belief that the school in this instance felt it could not overlook.” But Rita Schwartz, president of the National Association of Catholic School Teachers, commented:

“They should be happy that she’s not having an abortion. Don’t you think?... It should have been handled with love… She needs help here. She needs people to work with her, and that’s what they’re supposed to be doing.”

For schools that have fired unmarried pregnant teachers in the past, the issue has often been framed as one involving “scandal.” Catholic leaders argue that the “scandal” of having an unmarried pregnant teacher is inconsistent the school’s mission, and could suggest an approval of premarital sex. But such a framing is indicative of the same mindset behind the clergy abuse crisis, focusing on short-term “scandal” and losing sight of the more long-term and serious scandal caused by this focus.

For Aquinas, a scandal must be a word or deed that either is evil or has the appearance of evil, and which occasions another’s sin. In the case of the Catholic school, the deed is the premarital sex which led to the pregnancy, and the resulting sin would be a belief on the part of students that premarital sex is acceptable. However, in a world where sex is increasingly becoming separated from procreation, the presence of an unmarried pregnant teacher would likely have the opposite effect. Students are not likely to look at an unmarried pregnant teacher and think, “I, too, should have sex!” Instead, such a pregnancy might push the students to take more seriously their choices when it comes to sex and sexuality. It increases their awareness that premarital sex can and does result in pregnancy.

The “appearance of evil” suggested by the school also offers an overly condemnatory mindset when it comes to women in this situation. The school encourages a vision where we see an unplanned life in the womb of a mother, and what we focus on is her sexual sin. This might inhibit her from seeing her unborn child as an unexpected gift and joy to be welcomed into the world and, instead, Catholic schools encourage her to see her baby as a source of shame and an image of sin. Seeing evil in her pregnancy is indicative of the need for a new vision.

Also keep in mind that, according to Aquinas, a scandal can cease through an explanation or admonition. An unmarried pregnant teacher can explain to school leaders that she made a “mistake” and that she does want to model the school’s mission and values, especially through the joyful choice for life. Such a modeling would overcome the concern for “scandal” and would provide a model for students who may encounter unplanned pregnancies of peers or themselves later in their lives. The teacher, if a teacher of theology, might be especially well-suited to teach sexual morality, as someone who can approach it from a place of humility and personal experience with the complexities of the moral life, having lived the need to take responsibility for one’s actions, and learning to find joy in unexpected challenges.

By contrast, the decision to fire an unmarried pregnant teacher creates a serious injustice to the child and a scandal for the Church. For such a teacher, who does not have a husband that can provide an income and health insurance, losing a job means losing the ability to receive necessary care for the pregnancy. It leaves the woman, without insurance, in the position of having to take on significant medical costs with no income. The cost to have a baby without insurance can run anywhere from $30,000 to $50,000. She thus might run into debilitating debt and poverty just as she is trying to bring a new life into the world. In addition, just the worry about losing a job creates significant stress that could impact the pregnancy and the health of the child. The decision to terminate the teacher creates the key occasion that pro-abortion advocates argue necessitates the option to terminate a pregnancy.

The grave scandal comes from the decision of the school which is unjust to the child and which communicates to unmarried women that, if they should experience an unplanned pregnancy, the only way to keep their jobs would be to secretly have an abortion. One key argument raised by pro-abortion advocates is that access to abortion is required for women to have the same professional opportunities as men. In the Catholic school context, where men have not been penalized because of girlfriends’ pregnancies, Catholic schools give fuel to such arguments. This all undermines the Church’s pro-life position.

Moving Forward

Moving forward, Church leaders should think carefully before employing the concept of “scandal” to drive decision-making. One key thing to keep in mind is how short-sighted considerations can lead to long-term catastrophe for the Church. In complex situations, such as clergy abuse and unmarried teachers in Catholic schools, a wide range of perspectives should be brought to bear on decision-making. And care for the most vulnerable–the abused child and the unborn child and their families–should be at the forefront of considerations. Persons should never be sacrificed for “the institution.” Instead, we should keep in mind that “the institution”--whether the Catholic school or the office of the diocese–is the persons (or, at the very least, is created by and through them). And the point of “the institution” is to serve them.

During my years of teaching at Catholic School I was asked what should another teacher who was unmarried and just became pregnant do. I responded that "life is always a gift!" Happily the Sisters who ran the school saw things the same way and did not dismiss the teacher. Everyone helped her welcome her child. And the students learned the lesson of how grave the consequences of premarital sex can be putting mother and child in danger. The learned the correct way to respond to a pregnancy and the pitfalls of irresponsible sex. This article is an excellent analysis.

This is such an excellent analysis of the issue of "causing scandal" in the Church and of the Pharisaical hypocrisy often carried out in the institution. When I was a full time youth minister, I used to have recurring nightmares that I was pregnant, had no idea how, but that I was fearing I'd lose my job (despite the fact that in my waking life I was abstaining). That's how deeply it ran for me. Even though I was in no danger of becoming pregnant "illegitimately" , at least not consensually, I still felt an awareness of my potential to become pregnant as something that had the power to affect my career, and moreover my vocation as a youth minister. I don't know any people who have the potential to impregnate who have held the same fears.