Social media and mimetic rivalry: a case study (involving myself)

This is not an essay aimed an innocence. It is an essay aimed at escape.

Some will say that what I’m about to tell you here is a biased account that doesn’t have all the facts. They’re right.

This is my (current) best guess at what happened, at a high level. I’m writing this because this is also the best I’ve been able to come up with for myself. The names are pseudonyms. You can begin every sentence from here on out with, “It seems to me that…”

I. A Mimetic Conflict

Celebristan and Freshmanistan

I didn’t know Maria particularly well. I knew who she was. We didn’t follow each other on social media. We seemed to occupy very different spaces in the social media world. Her Instagram account had more than twice as many followers as mine. Maria had recently focused her account on issues of race, while I focused on a range of issues such as sexuality, abuse, institutional dynamics, and the philosophy of desire, as well as issues of race, though in an emerging way (I had started to explore race and racism more seriously only in the last couple of years). Maria and I didn’t have much of a reason for conflict before. This, I suspect, is largely because our worlds of longings were markedly different.

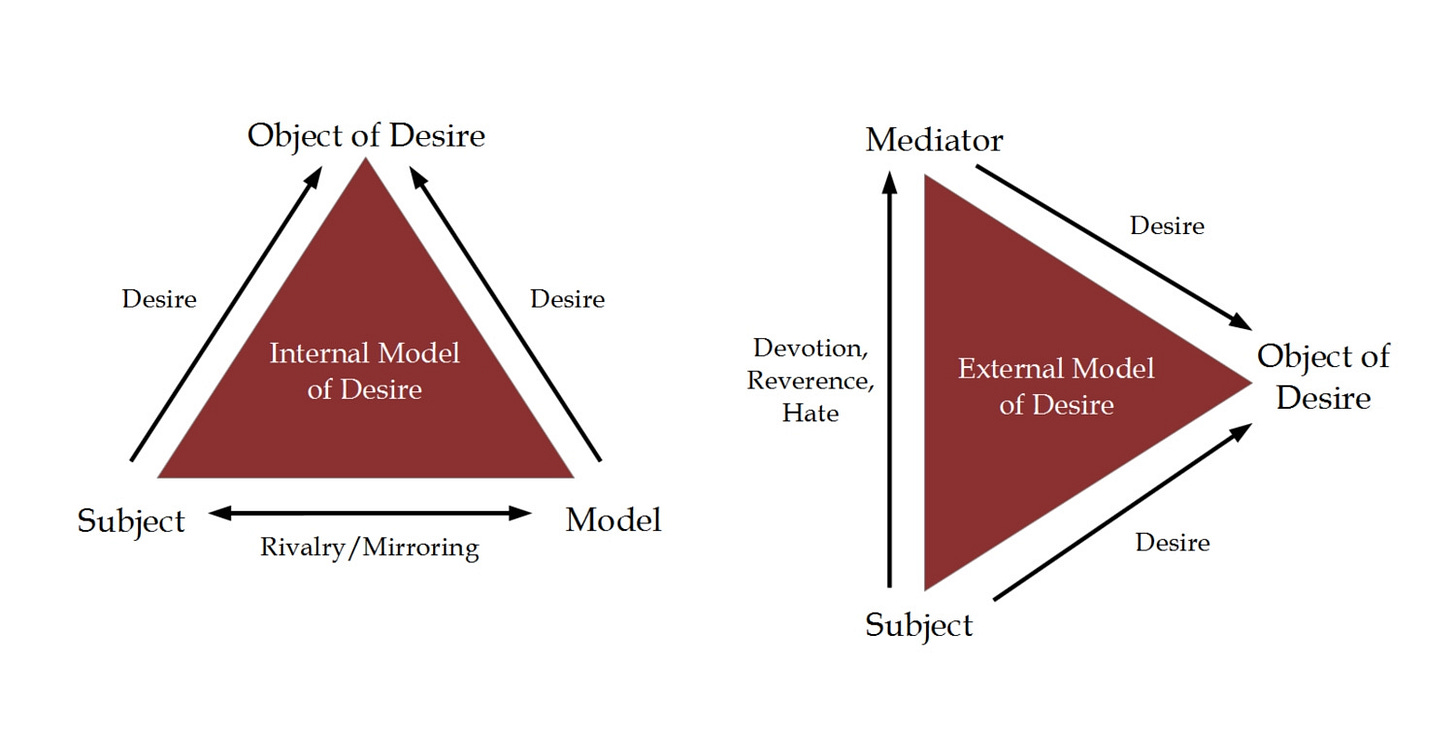

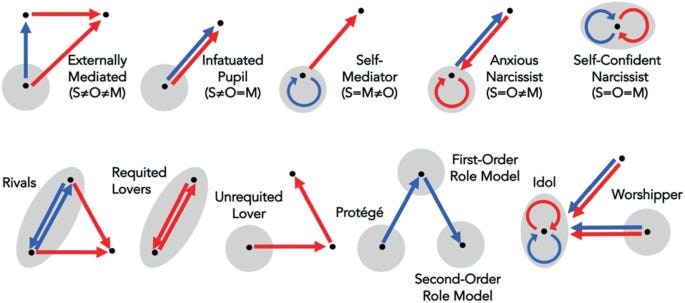

In Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life, Luke Burgis draws on the work of René Girard to help explain the origins of rivalries. (Most of Burgis's book is a summary of Girard's ideas, applied to present problems.) Burgis argues that we all have things that we desire, and we largely look to others to “model” how we are to desire things. This is central to Girard's mimetic theory. (“Mimetic” and “mimesis” are related to the more common English words “mimic” and “mimicry.”) None of us are independent desirers. Our entire lives, we look to others to help us learn how and what to want. Those others serve as mimetic models. When we see those others desiring, the desires can become contagious. Without realizing it, we "catch" those desires in various ways. Those who we look to in order to learn desire are called “models.”

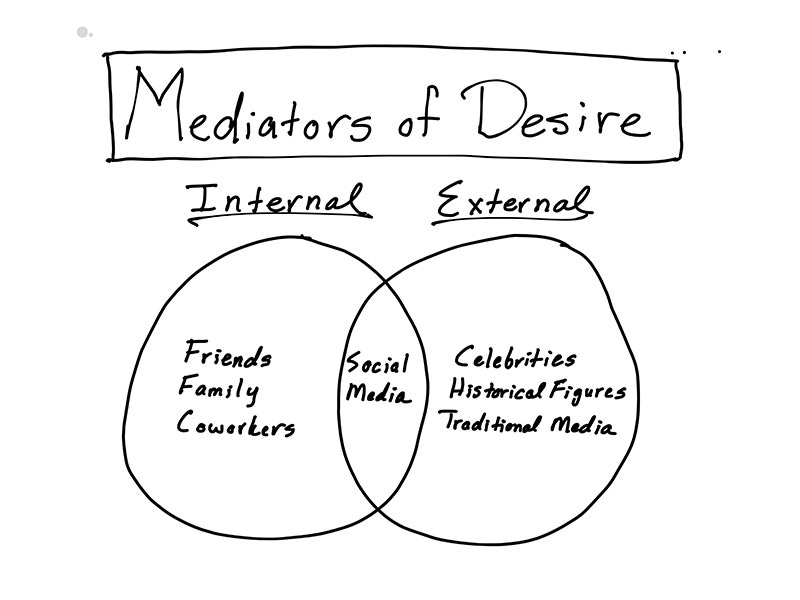

Burgis says that there are two kinds of models. The models of “Celebristan” (Girard calls these "external mediators of desire") are those who aren’t in our social circles, who stand apart, and who we look up to as models. This could be a professor or author we admire, or a celebrity, or a major political or social figure. We are unlikely to interact directly with them, and so when we look at them as models of desire, there is unlikely to be conflict.

The models of “Freshmanistan” (also known as "internal mediators of desire"), on the other hand, are the those in closer proximity to us. They might be coworkers or friends or mutual follows on Twitter. They are models where we are aware of one another, and where we can influence one another. There’s something threatening about these models because we can see one another wanting the same things, and “rivalry is a function of proximity.” Burgis argues that most conflicts can be traced back to mimetic rivalries.

Mimesis has a powerful tendency to both bring people together and tear them apart. Girard writes in his introduction to A Theater of Envy:

“Imitation does not merely draw people together, it pulls them apart. Paradoxically, it can do these two things simultaneously. Individuals who desire the same thing are united by something so powerful that, as long as they can share whatever they desire, they remain the best of friends; as soon as they cannot, they become the worst of enemies”

Girard writes of a “perfect continuity between concord and discord.”

I saw the contagions of Freshmanistan in my graduate school’s Catholic Studies program. The young men in the program often served as models of desire for one another. Groups of them seemed to all have a crush on the same woman. Then, inexplicably, they would all move to a crush on a new woman. There were plenty of women in the program, but somehow they always tended to land their focus on the same one, and then shift their focus collectively. Because they were in the same social circles (usually friends), this would create unspoken rivalries and insecurities within the groups. Sometimes they would resolve. Sometimes the friendship would dwindle away in the face of the mimetic tension.

Or consider the experience of falling in love with a person. Part of what can make this experience transformative is that it enables us to see and accept and love ourselves in new ways. The love of another for us can give us models of desiring wherein we come to a new appreciation of our own dignity and worth, where we can learn to desire new possibilities for ourselves. One of the great gifts of love that we can offer one another is a model of desire where we come to love, not only the other, but also ourselves. On the other hand, falling out of love can be threatening, in part, because the model of desire for ourselves is threatened, and we can experience conflict not only with the other but also with our own sense of self. Part of the reason that a breakup can be so destabilizing is because we are losing a key model of desire and are thus losing access to a key way in which we come to love ourselves.

Thinkers from Episcopal theologians to gay rights activists have explored the ways in which desires are not merely innate, but are formed through experience, perspective, and and competing narratives. Often, we can be mistaken about the nature and sources of our desires. What Girard (and, by extension, Burgis) provides to this conversation is an attention to the ways in which we look to “models” in the world, who pass on their desires to us as if they are contagious. When we look to another, one thing we observe is how they desire, and this observation changes us. This is one reason why Christianity has focused so often on the life of Christ and the saints. When we look at them, we are not merely observing. We are being changed.

Maria and I hadn’t experienced conflict with one another, mostly because we had not lived in Freshmanistan together. We couldn’t serve as models to one another, partly because we weren’t aware of what each other wanted, or even what the other was doing, except in a general sense. I was generally aware of Maria in the world. I knew vaguely who she was. I have no idea what she knew about me. Then we entered Freshmanistan together. And chaos ensued.

But before Maria and I entered Freshmanistan, Maria (BIPOC) and Nicole (white) had spent time there together. Both Maria and Nicole were known for their social media platforms. Maria had recently been focusing more and more of her social media presence on issues of race and racism. Nicole focused primarily on abuses within the Church, which had meant that she also spoke about race and racism, and she promoted BIPOC Catholic accounts. Nicole had recently eclipsed Maria in her following, and though Nicole had promoted Maria’s account, Maria did not want Nicole to occupy the same space as her. Maria told Nicole that she was harming BIPOC people with her account. Something bubbled up to the surface, where these accounts came into conflict and could not coexist peacefully. Eventually, Nicole became overwhelmed and shut down her account. Nicole and I were friends. I was shocked.

And there was the live event. Nicole's account often focused on the question of deconstruction, something which she had studied extensively. The conflict first arose when Maria accused Nicole of engaging in appropriation because Nicole was a white woman running an account on deconstruction, despite the fact that Maria (as she admitted herself) hadn’t done much research on the topic. Shortly after Nicole shut down her account, one of Maria’s friends set up a live virtual event on deconstruction and included Maria as one of the “panelists.” At the start of the event, the host stated that there would be no “tea” spilled during it concerning the controversy between Nicole and Maria, but that there was some “shade,” presumably on the part of the panelists towards Nicole and those who had supported her. I thought about this later when the question of “turf wars” came up, and then again as I studied the ways in which mimetic rivalries lead to a sort of consumption and assimilation.

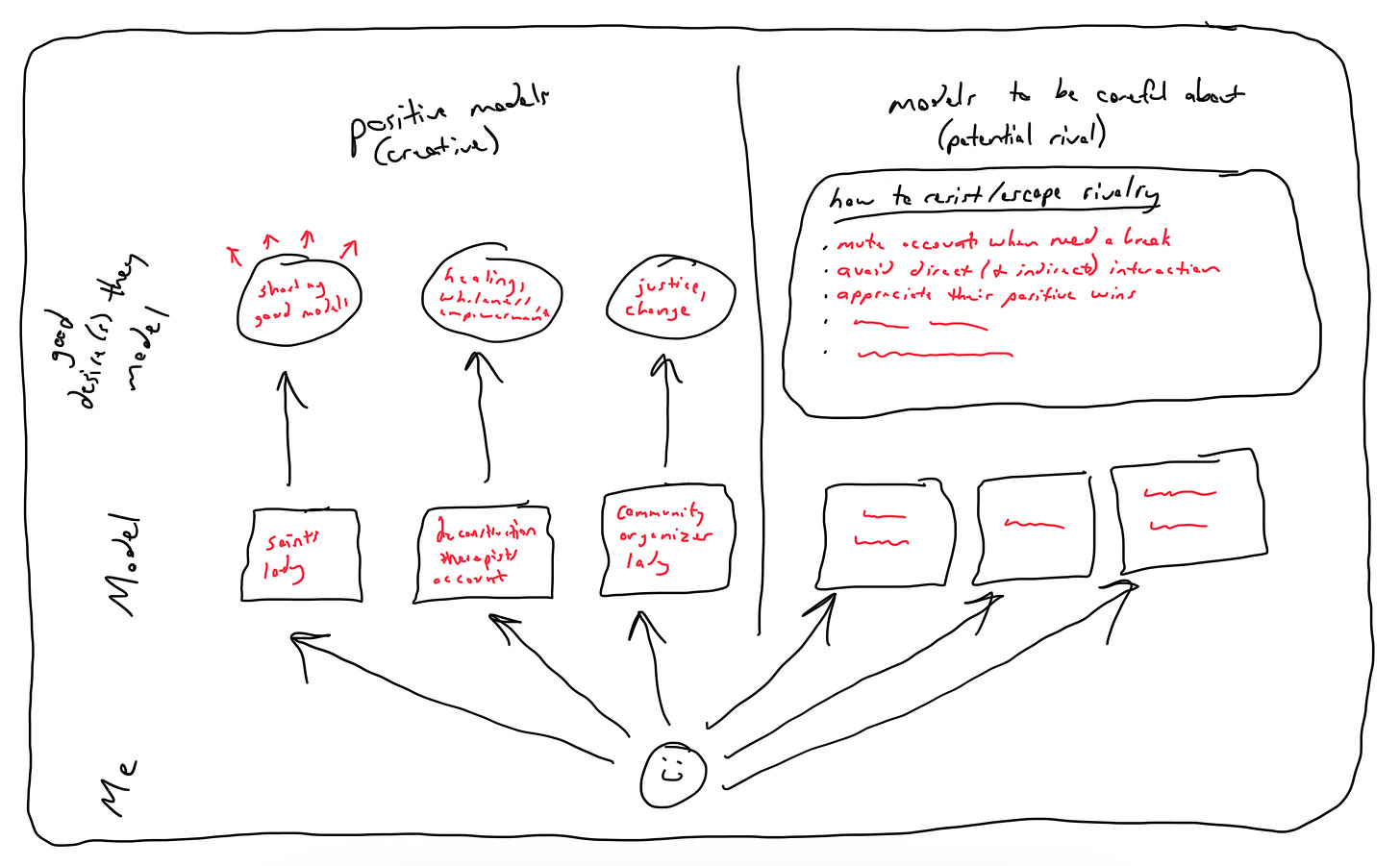

Burgis argues that there are negative cycles of desire, and there are positive cycles of desire. I’ll talk about the negative cycles in just a bit. But first I’ll share a positive cycle I enjoyed for a time but which is no longer in existence.

Burgis argues that mimetic desire is not necessarily good or bad. It is, rather, an inescapable feature of the human condition. Our failure to recognize it in our lives tends to contribute to rivalries and conflicts. But the more we come to understand its role in our lives, the more we can transform our relationship to it for the better. One key to a better relationship with mimetic desire is the practice of empathy. Another key is exerting the sort of leadership where one helps others imagine new ways of wanting, and also shift’s the “center of gravity” of desire away from oneself to focus onto good goals. Doing so reduces rivalries and their conflicts, and enables various forms of creativity.

This had been my experience of Nicole. She and I had occupied very challenging spaces in the Church. There were certainly opportunities for us to compete over the same space, since we both focused on institutional abuse and harms and were facilitating conversations with our Instagram followers about Catholic ministries, leaders, and issues. And we had a certain proximity, as my account had begun engaging regularly with her account, and we would direct our followers to one another. We didn’t always agree, and we had different approaches to our platforms, but somehow it all became very complementary. I had a sense that our successes, while not bound together, were shared in some way. I was surprised to find that such a relationship could be cultivated between two social media accounts. I have many friends that I follow on social media, and many accounts on social media that I like and respect. But the sort of social media friendship between myself and Nicole (and, for a time, a third account), and the cycles of creativity and hope that friendship fostered was not something I’d before experienced on a social media platform. When Nicole shut down her account, that cycle of creativity gave way to another cycle, one which I don’t feel I’ve been fully able to escape.

As Nicole was winding down her account, I reviewed the conflict between her and Maria. I decided to address it. I spoke about it directly and publicly on my account. I wrote about my disagreements with comments Maria had made regarding antiracism. While offering critiques of some of Nicole's choices during the conflict, I largely defended her as a victim in the situation. I argued that Maria had behaved in a way that was manipulative and harmful.

A part of me thought that my comments would be the end of it. Maria and I hadn't engaged one another on social media previously. I had a much smaller following and thought that maybe she would see my comments but that I wasn't significant enough in her world to merit a response. But I was wrong. Maria took notice. We entered Freshmanistan. And I didn’t realize it, but Maria had brought friends.

Turf wars

Maria had engaged in behavior which I considered to be aggressive, manipulative, and malicious, both towards me and towards Nicole (as well as towards others who had attempted to interact with Maria and then, as they shared with me, were scared away). She made accusations that the BIPOC people who had supported Nicole were “not helping.” At one point, Maria messaged me privately and we had a series of quick heated exchanges. Then she publicly and without warning shared a screenshot our messages on her account. This incensed me. Then she told me our conversation was over and blocked my account. But it wasn’t over. I didn't realize it at the time, but she was becoming a mimetic model for me. And, as I would discover later, I had become one for her.

Burgis writes in Wanting:

“When mimesis takes over, we become obsessed with vanquishing some Other, and we measure ourselves according to them... When a person's identity becomes completely tied to a mimetic model, they can never truly escape that model because doing so would mean destroying their own reason for being.”

After the immediate conflict, I found it incredibly difficult to disentangle my engagement with social media from it. A number of Maria’s friends reached out to me, people whom I had followed and respected and admired and who had served as models for me in various ways, to inform me that I was in the wrong. At one point, I was told that I was being an “occasion of sin” for others. (This, by the way, is an accusation leveraged regularly against LGBTQ+ people in the Church, and so is a highly charged accusation when made against us. This highlights the need to develop intersectional approaches to conversations within the Church. Part of what made the dispute between Maria, Maria’s friends, and myself so personally difficult was the ways in which its dynamics and rhetoric mirrored harmful dynamics and rhetoric I had experienced as a gay man in the Church, though I will save exploring that particular subject for perhaps another time.)

I found myself checking those accounts in the following days, watching for ways in which they might address the conflict between Maria and I, though indirectly. This is a common mimetic practice in the twenty-first century. (How many of us have checked the Instagram of the other half of a bad breakup, and felt anger when they appeared to be happy in photos?) Meanwhile, I found myself gauging the success of my account, in part, by the ways in which it differed from Maria’s: by how measured my tone was in comparison, by my openness to critique, by my willingness to take open accountability for bad behavior, by my move away from black-and-white thinking and towards nuance, by my directly addressing the conflict rather than engaging in practices like "vaguebooking," etc. These measures are not necessarily bad, but the comparative mode driving them made my own sense of success depend, in some way, on the lack of success of Maria’s account. Because of this, success was also a constantly shifting goalpost.

Overwhelmed, I had tried to pull away from the conflict. But in the weeks that followed, I was pulled again and again into this comparative mode as people reached out to me about Maria’s behavior. For weeks, I received messages from people sharing that Maria was engaging in “vaguebooking.” One of the challenges of social media is the ways in which conflict can be both open and hidden. For example, shortly after Maria blocked me and I had switched my own account to private and set up a some antiracist book clubs, I was informed that Maria posted about how book clubs don’t solve problems; shortly after I made a chess analogy, another person shared that Maria had posted a chess analogy critiquing mine (without actually naming me); another reached out and told me that, after she had shared some of my content, Maria had messaged her, criticizing her for doing so and insisting that sides had to be chosen. Though Maria had blocked my account, I continued to be made aware of her veiled jabs at my account. I started hearing stories of Maria doing this to others.

And some sort of triangulation also seemed to be emerging. I started receiving critical messages from others that, after doing some digging, I realized didn't follow my accounts but did follow Maria’s. One of those messages accused me of benefitting from my "white privilege" in the conflict with Maria. (I'm brown.) I changed my settings to allow messages only from my followers. One person reached out to inform me that Maria had engaged in this same behavior towards her after they’d had a disagreement. Like Nicole, that other person decided that the best course of action would be to withdraw from spaces that she felt Maria dominated and where Maria was allowed to engage in this behavior. I decided to openly write about the conflict with Maria. I collected all of our public posts from the conflict and shared them in order. I wanted a clear record of what had happened. When doing so, I was accused by others with larger social media platforms (all self-identified friends of Maria’s) of initiating "turf wars" or trying to "take down" or "build something against" her. Criticisms leveraged against me almost always involved some reference to an aspect my my identity or background, or allegations concerning my motivations.

When an accusation like this would be made against me, an inclination would flare up within me to try and figure out who was on which "side." So while I was actively trying to work against this inclination, the accusations against me would fan the flame of mimetic rivalry. Despite myself, I found myself behaving as if I were engaged in “turf wars.” This is partly because telling someone to stop engaging in "turf wars" is like telling someone to stop being anxious. The effect is usually to cause an increase. At times, the accusation can create the thing opposed.

This is one of the strange features of mimesis and mimetic rivalry. Actions like accusing another person of engaging in turf wars can themselves be the criticized activity itself. In my view, Maria had driven "turf wars" with Nicole, as I suspected she had done with others before Nicole, which was why the only way for Nicole to escape the conflict was to shut down her account. I thought back to that live event with Maria and her friends, and later connected it to the possibility of “turf wars.” Still, it's possible that Maria thought I was initiating "turf wars" so that I could take over spaces she was occupying.

But regardless of who initiated the "turf wars," or whether one had really existed, the accusation of of engaging in "turf wars" (whether by Maria or me or Maria’s friends) was, at the very least, a confirmation that such "wars" were occurring and, possibly, were what officially created them. If Maria or I exercised executive power to engage in conflict, those third parties may have been playing the role of Congress in the Declaration of War. Opposition can be like love: simply speaking the thing can be what makes it real.

If you want to end conflict, you need to do more than name it. You need to provide a pathway out. As I will share in subsequent parts of this essay, Burgis gives some possibilities for this pathway.

People

Surely some will read this and think this is all over-dramatic and that such analogies are a function of hyper-sensitivity. This may be true to a certain degree. It's also important to keep in mind that these are all real people, that these are all actual inter-personal communications, and that real feelings were involved, on all sides. This all might matter in a way similar to the ways in which Jane Austen dialogues matter. Little insular spats and insecurities can speak volumes about the human experience, if we take the time to really listen and unpack them.

Whether you realize it or not, the dynamics outlined in this and subsequent parts of this essay are dynamics we all find ourselves in all the time. They might be seen in the contagion of road rage, when we check in on the Instagram account of an ex, when we hear of a classmate’s professional success and feel pangs of envy, when we interpret or participate in partisan politics, in the bizarre behavior of a narcissistic boss or child’s class bully, and when we focus on ways to anticipate the movements of and overcome our enemies. Mimesis and mimetic rivalry are inescapable parts of human life, and they show up in ways big and small. Learning to recognize and respond well to them can open up new possibilities for communion and creativity. That is my hope for the future.

Mirrors

When considering that conflict through the lens of mimetic theory, one thing we may have all been doing was serving as mirrors to one another. Consider again the comparisons I spoke about earlier, where I defined my success (at least in part) by not doing what Maria was doing. The appearance of opposition is misleading. What I was actually doing was engaging in a form of imitation. In defining my success by doing what Maria wasn’t doing, I'd set up Maria as my model for success, allowing her to establish the criteria for success and defining myself by those criteria. Burgis calls this imitation "in a mirrored way." It's as if we were doing the acting exercise where one person acts as a “mirror” to the other: when they raise their right hand, I raise my left hand. I think I'm doing the opposite but, in a deeper way, I'm doing the same.

This "mirrored imitation" both makes us more like the model and also further drives the rivalry. Because of this mirrored imitation, my success is dependent upon both my ability to counter the model and also the model's failure. And because success is bound up in the defeat of the model, any proximity to the model is a threat. The more I encounter or engage with or see the model (or see others encountering, engaging with, or seeing the model), the more I feel threatened and need to defeat the model.

A former student of Rene Girard once recalled his professor opening a class with the words, "Human beings fight not because they are the different, but because they are the same, and in their attempts to distinguish themselves have made themselves into enemy twins, human doubles in reciprocal violence." We fight because we want to occupy the same ground, because deep down we carry some fundamental sameness. (This is one danger of friendship, which Girard discusses in an essay on Shakespeare’s The Two Gentlemen of Verona.)

But it is the other way around as well. It’s not just that we fight because we are the same. We are also the same because we fight. The more we fight, the more we come to be like each other. The more we attack or critique or subdue, the more we risk becoming the thing we think we are opposing. This is partly why victims who fail to transcend their victim status have a tendency to become victimizers: as we focus on ourselves in relation to some victimizer, we can fall into the mysterious human tendency to extend the harms they have given to us. "Winning" over the victimizer is not sufficient to escape this trap; at times, it can cause us to fall more deeply into it. Burgis writes, "We should choose our enemies wisely, because we become like them."

We can observe this in narratives all around us. One interesting feature of extended victim narratives, such as that of Jessica in the show 13 Reasons Why, is how the victim must struggle with how they are to relate to their victimizer. They often move from a full withdrawal to a direct rejection and oppositional stance to a more healed position that involves a much more casual and much less attentive relationship to the victimizer.

If I had criticized Maria for her aggression, malicious behavior, and seeming lack of boundaries when it came to engaging others, I found myself moving in this direction as well. I now look back at various ways I responded to the conflict at its most heated points, and I feel embarrassment at the ways in which I failed to resist, got caught up in, and contributed to its frenetic energy. I recognize ways in which I fed into toxic mimesis. At one point, I had criticized Maria for failing to respect others' experiences of trauma. Without diving into the details here, I'll just say that I did this myself at one point. As I was trying to address what I found most harmful in Maria’s forms of engagement, at a couple of points I found myself using the very tactics I had criticized.

Bullfighting

After the immediate conflict, and after I was able to find a certain re-grounding of myself, I tried to only address it by focusing on particular public posts that were shared during that time. I tried to treat the conflict as a sort of enclosed space, so that the conversation could be about particular particular issues identified in public comments and dynamics. But, as I’ve seen as I’ve tried to address other controversies in the Church, I was told at times that I didn’t have all the facts. Maria’s friends reached out to tell me they had more context that I did, and thus I shouldn’t be commenting on the matter at all. Something came up which sought to drive away the issues I had highlighted and instead focus on something else, something undefined, and something which had supposedly put my original focus of Maria’s criticisms in the wrong, but something which no one was willing to share. Perhaps that was part of the point.

There was something right to those messages I was receiving. I didn’t have all of the context, though I had much more context than I was letting on at the time. But this is partly why I chose to only comment on what had been publicly posted. And that choice highlighted the nature of those messages. There was something deeply manipulative about them. They said, “This person may have made public comments, but you’re not allowed to respond to them because you don’t have all the context behind them.” In other words, “This person can say publicly whatever they want, and you have to just silently take it because you don’t know everything about what they’re saying.”

I could recognize the manipulation occurring, but I couldn’t really get myself out of its effects. I then thought, “If they’re giving me this kind of messaging, they’re probably giving it to others as well.” I read the messaging through the lens of rivalry. I shared some posts about this kind of messaging, how to recognize it for what it was, and how to respond to it. Without recognizing it at the time, I was feeding the rivalry. I now wonder whether I was engaging in “vaguebooking.” (To what extent is this essay itself a form of vaguebooking, potentially illustrating just how challenging it can be to escape a mimetic rivalry?) It was exhausting.

Burgis argues that "[b]eing in a mimetic rivalry is like being a bull in a bullfight." Bullfighting is primarily about psychology. The matador leverages the inclination of the bull to hurl itself at the cape again and again, until the bull has reached exhaustion and can be slayed by the matador. Burgis says that the mimetic rival is like the matador:

"The rival determines what a person wants next, which goals they pursue, what they think about when they go to bed at night. If a person doesn't realize what's happening, the game will bring them to the point of exhaustion, and maybe worse."

I don't think this is quite right. In a mimetic rivalry, both persons are the bull, and the matador is the rivalry itself. Both are driven to madness. Even if one person "wins" over the other, the "winning" consists primarily of a further entrenchment in a life of mimesis. The rivalrous person has been caught in the black hole of mimesis and will find themself in another rivalry in a matter of time, subjecting oneself to the game again where all lose.

To the extent one feels threatened by a mimetic model, one lives in Freshmanistan. I don't know how Maria would characterize her relationship to all of this. I still feel parts of myself in Freshmanistan, and I don't want to be there. The next steps are trying to make my way out.

II. Mimesis and social media: the problems

Social media conflicts are different

My conflict with Maria was hardly my only conflict from the last year. I had been involved in a number of conflicts within the Church, usually by writing on them. One such conflict was the series of posts I had written about misogyny, abuse, and the lack of care for victims by leaders of Bishop Barron's Word on Fire Ministries. That conflict garnered lots of public attention, drew in significant readership, and put pressure on me to manage a complex story that (in my opinion) I was not fully equipped at the time to handle. (Fortunately, I received a lot of help.) The tactics of the ministry and its leaders in response were nasty at times, accusing me of lying and defamation and engaging in a smear campaign.

But, as I reflected on conflicts like those with Word on Fire, I realized that they didn't have nearly the same personal impact as the conflict with Maria. Why was it that this individual's social media account took more of a personal toll than public accusations against me by a national ministry? The type of conflict initiated by my engagement with Maria was very unusual for me. How did this happen?

Answers might be found in the dynamics of mimetic desire in the world of social media. The conflict Word on Fire occurred primarily through a series of written statements issued on websites, rather than through the churning immediacy of social media posts. In addition, and partly because it is not primarily a social media platform, to the extent Word on Fire might be a model for me (whether a positive or negative model), the organization and its leaders exist largely in the world of Celebristan. To my knowledge, we don't have many mutual admirers that engage us both, and while I am aware of Word on Fire in the world, I don't have a sense that either Word on Fire or its supporters are watching me (or vice versa).

Partly because the conflict occurred over extended written statements and series of interviews, success could be measured in the ability to share the stories of survivors and whistleblowers in ways that felt empowering to them, rather than in the engagement of a mass of people on a constantly churning platform. And because the conflict also occurred at an organizational level, and included sharing recommendations for change, success could be measured against those recommendations, rather than against a count of readers or followers or mutual followers. Because the point wasn’t really about “defeating” the ministry, but was about helping those who were harmed and those who may be vulnerable in the future, the continued presence of Word on Fire in my world doesn’t feel particularly threatening. (Others who may be in Freshmanistan with Word on Fire, such as former employees or the victims who personally know current employees, may feel differently, and rightly so.)

By contrast, because Maria and I related to one another primarily as social media platforms, once we entered Freshmanistan, it was very hard to get outside of it. We continued to have mutual friends and followers, something which I only discovered during the conflict and now cannot forget. There were and are many single degrees of separation between us. The rivalry has not actively and openly continued, but it has moved "underground" in a way. And because of the structure of social media, I worry that it may take a long time to go away.

Part of the problem may be one of envy, which Girard also discusses at length. He writes in A Theater of Envy, “Like mimetic desire, envy subordinates a desired something to the someone who enjoys a privileged relationship with it.” In a mimetic rivalry, one assesses the landscape to view what the rival possesses, and all these possessions can become a threat to one’s perceived place in the world. In the world of social media, these possessions consist primarily of content, engagement, and connections. The places of overlap are the most threatening, and for me those places consisted primarily of people (or, rather, various people’s accounts). What I didn’t realize at the time and am only starting to unpack now is the ways in which I began to feel the pangs of envy as I discovered many of my connections were our (Maria’s and my) connections. As some seemed to turn against me and to take the “side” of Maria, a part of me worried they all would. A part of me felt envious of those who already had, those friendships which I had previously felt developing but which had suddenly soured.

This is not an accident. It is part of the structure of social media. It is part of the world we are driven into.

Girard notes that we find ourselves “predisposed” to what our mimetic models desire. This includes our rivals. One way in which this could kick off a toxic cycle of desire on social media might be a situation where I feel insecure about connections I share with a rival. I behave in ways so as to secure those connections myself. My rival notices me desiring (or just perceives me desiring) these connections, which inflames the rival’s desire for those connections themself. So they behave in ways to secure those connections, in ways contrary to my own security.

This happens all the time on social media. But we don’t talk about it, partly because we don’t want to admit what we wish we had. As Girard writes, “envy is the hardest sin to acknowledge.” Admitting envy towards a mimetic rival is doubly embarrassing, because it involves admitting that we want things from those we project as lesser than ourselves. We cannot face the shame of envying our rivals (or, rather, that we envy with them).

Social media as a world of imitation

In Psychology Today, Burgis spoke on how social media specifically operates to create and recreate our desires. As he argues in Wanting, we don't long as independent beings, but as mimetic persons that are part of an "ecology of desire." We don't live in worlds of independent desires. Rather, our desires are created and influenced and mediated by one another. Social media draws on these dynamics through systems of follows and likes. When we encounter an account that is followed by others in our social network, we are more likely to consider following that account ourselves. And when we see content which has generated a high number of likes, we are more likely to pause and observe it than if we come across content with minimal engagement. It’s not merely the content itself which catches our notice, but whether others have engaged with it. Others communicate, whether explicitly or subtly, what is good to desire, what is worth wanting, what should capture our attention and be worked towards.

Certainly, some desires seem intrinsic. But even those desires are subject to directional guidance; general desires are always susceptible to suggestion, in ways that can alter them. When it comes to desire, there is never only nature. Nurture always plays a role. Currently, social media is among the most influential nurturers when it comes to the development of desire. Burgis writes, "Mimetic desire is the real engine of social media." When we open up Twitter or Instagram or Facebook, what we are encountering are a series of accounts and posts modeling desire and awaiting our imitation. We are given desires for beachy vacations, for "hot takes," for toned bodies, for pretty piety.

In a platform of “hyper-imitation,” where the incentive structure is built around “trending” and “going viral,” we are being set up for mimetic failure. Burgis writes, "Social media platforms like Twitter seem built to propagate [memes]: words and ideas are spread through perfect imitation every time someone shares or retweets them." The most prevalent social media platforms are designed to incentivize that which can drive the most imitation. According to Burgis:

"Social media platforms thrive on mimesis. Twitter encourages and measures imitation by showing how many times each post has been retweeted. People are more likely to use Facebook the more they are engaged with mimetic models, rivals whose posts they can track and comment on."

Note how the primary indicator for success on most media platforms is “engagement,” measured by the number of followers, likes, shares, and views. This is the only universal measurement across these platforms. Typically, it is the only measurement. Note that these measurements are measures of modeling and imitation.

The real winner

Most major social media platforms are structured in ways that encourage and fuel these conflicts. The matador may not just be the rivalry. The matador may also be the platform. And the game is built for it to win. Because they tend to drive engagement, the most prevalent social media platforms drive and reward mimetic rivalries.

Over the last year, I generally became disillusioned with my own ability to navigate these dynamics in a consistently healthy and productive way. I withdrew significantly from social media, in part, because I didn’t have confidence in my capacity at the time to manage these spaces in a way that is truly to the benefit of myself and others. Burgis writes that one can transcend that common destructive cycle and come to a second cycle: "It's possible to initiate a different cycle that channels energy into creative and productive pursuits that serve the common good." But the structure of most social media platforms inhibit our ability to do this. Here, I’ll share four ways that the structures of social media help drive mimetic rivalry and conflict.

1. The drive for engagement privileges anger.

The structures of social media often don't lend themselves to creative cycles of desire. Instead, they more readily lend themselves to toxic rivalries. Toxic mimesis doesn’t just come from the anger and outrage that dominates social media. The prettier our feeds, the more anxious we become. This is partly a function of envy, a function of feeling a desire to capture or compete with and for the objects of our feed of models’ desires. Usually, this envy is beneath the surface. Sometimes it bubbles over into open bitter conflict.

But anger and outrage do have a privileged place on the most prevalent platforms. Mimetic conflict helps drive the emotion which best aligns with the goal of social media platforms to increase engagement: anger. In Wanting, Burgis discusses a 2013-2014 study on influence and contagion on the social media app Weibo. Burgis summarizes: “They found that anger spreads faster than other emotions, such as joy, because anger spreads easily when there are weak ties between people—as there often are online.” Social media ties are often shallow, but they are real. What many of us fail to take into account is the extent to which social media platforms privilege, promote, and incentivize the weak ties that increase platform use. For platforms that are concerned with constant growth or (like Twitter) whose funding relies on advertisers, such ties are essential to their success.

2. Flat structures drive us all into Freshmanistan.

Burgis discusses at length the development of the online retailer Zappos. Shortly after Zappos was sold to Amazon, Zappos's founder and CEO implemented a new flat management structure called "holocracy." Under this structure, formal hierarchies disappeared and self-organizing teams were responsible for various projects. But the impact to Zappos was similar to the self-organizing communes discussed in Jenny Odell's How to do Nothing: conflict and confusion ensued. As journalist Aimee Groth noted about Zappos once it implemented holocracy, "you still had a few people who had infinite power because they had a strong relationship with Tony." Burgis writes that what arose was "a hidden web of desire that nobody could decipher." Everyone occupied Freshmanistan, anyone could serve as a mimetic model, and much of the company culture came to be characterized by anxiety, confusion, and dysfunction.

Burgis could have been discussing social media in this section of his book. Much space has been given to discussing how the engagement algorithms of social media contribute to conflict, but much less space has been given to exploring the ways in which the apparently flat structure of the most prevalent social media platforms create and contribute to chaos and conflict. On social media, we are all in Freshmanistan. And while there are those who may exist on social media in a Celebristan relationship to us, the barrier preserving Celebristan on social media is fickle, thin, and porous. Hierarchies have endemic problems. So do flat structures.

3. Platforms are built on the demand for models, and they demand we all become models.

Another key aspect of social media is how it drives all of us to promote ourselves as models of desire for others. Burgis discusses Eddie Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud who ran a series of successful PR campaigns in the mid-twentieth century. In 1929, the American Tobacco Company asked Bernays to break the taboo against women smoking in public. A. A. Brill, a student of Freud, advised that the cigarette represented male sexual power as a phallic symbol, and the cigarette would need to be transformed to become desirable for women. But Bernays knew that messaging cigarettes as "torches of freedom" would not be enough. He needed to give women models who could model the desire for this view of smoking. He hired a group of women to participate in the revered New York City Easter Day parade and openly smoke with the appearance of strength and defiance. The next day, newspapers across the country featured photographs of these women, depicting them as trailblazers who would destroy discriminatory taboos and represent new freedoms. Part of the power of Bernays's plan was that it appeared somewhat spontaneous and relatable. The women were selected, in part, because they were attractive but not too attractive, in a way that felt aspirational but also attainable.

In the past, a select group of models tended to be selected and promoted in all kinds of areas, from fashion to the academy to fitness to social activism. And education often functioned to help make one aware of various types of models. Part of the value of a liberal arts education was that it exposed one to models who had withstood the test of time, and who presented a diverse array of desiring. Participation in the life of the mind involved engaging with those models, promoting those deemed most worthy, and seeing oneself as part of a sort of hierarchy that could create a kind of order and process for development.

Part of the challenge of social media is that the focus on identifying and promoting a set of models has gone away. Instead, social media tends to push everyone to view everyone as a model of desire, and to constantly present ourselves as models. The push for originality, personality, and "authenticity" makes us all models and subject to the kinds of scrutiny that models face. The women in Bernays's campaign were a small group who might be subject to scrutiny and visibility in a news cycle. Today, those women are all of us who post publicly on social media accounts, and who feel ourselves subject to the scrutiny those women may have experienced. But today we experience it in a more (and increasingly) pervasive, constant, and demanding way.

On social media, as consumers, we are chasing after projections of others’ desires, presented before us as possibilities for imitation. As “creators,” we are projecting our own desires as possibilities for others to imitate. And these two processes intertwine, whereby our projections are imitations presented for others to imitate under guises of individuality. Why is it that fads and trends populate so much of social media, whether they be content types, design and format choices, and methods of engagement? It’s because on these platforms we are living in imitation machines. Burgis suggests that those who will do best (and be most able to avoid toxic rivalries) are those most ready to acknowledge this. Those who insist that their social media lives are solely presentations of their “authentic” individual personhood are deluded.

Failure to acknowledge the role of imitation and work against toxic mimesis will get us into trouble. As we imitate the desires of the models around us on these platforms, we will often feel threatened by the limitations of the objects pursued, whether they be status, privilege, space, followings, or measures of engagement. To the extent our models come closer to us, and we get closer to attaining the objects we perceive as limited, we will begin to fight. When the fighting bubbles into public spaces, engagement will balloon. And, again, the platform will win.

4. Vague missions drive confusion and conflict.

As these platforms have become major corporations, their sine qua non has become the generation of increased profitability. Facebook's official mission statement is: "give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together." For reason's I'll discuss shortly, Twitter's mission statement is slightly better: "The mission we serve as Twitter, Inc. is to give everyone the power to create and share ideas and information instantly without barriers. Our business and revenue will always follow that mission in ways that improve – and do not detract from – a free and global conversation." But it is clear that profit is the sine qua non of these companies, that their leaders will make compromise after compromise in the name of profitability.

These corporations are increasingly making moves towards vague and values-oriented mission statements such as Facebook's, something which may not always be a good thing. Again, consider Burgis's discussion of Zappos. The company started with a mission to make buying shoes easier. Zappos leadership realized that this required a focus on customer service, which required a strong company culture, which led to happy employees and customers. This happiness, in turn made the shoe buying experience easier. The clear mission of the company led to a creative cycle for the company that led to its meteoric rise and success.

Eventually, however, Zappos moved away from the core mission of what it was uniquely able to provide, and its founder decided that the goal of his business was to make people happy. He started the Downtown Project, geared towards revitalizing run-down parts of Las Vegas, and intertwined its culture with Zappos. The Downtown Project would be struck with a series of suicides completed by its leaders and participants over the next couple of years. Examining both of these, Burgis writes:

"When the focus shifted away from shoes and customer service to happiness, the number of mimetic models multiplied. It was unclear who was happy and who was not; whom to imitate and whom not to imitate; who was a model and who was not. Zappos and the Downtown Project had turned into Freshmanistan."

While there are many ways to read the disasters that faced Zappos and the Downtown Project during those years, Burgis makes a number of important points. And this raises an important question for those of us who manage accounts on social media platforms: what exactly are we doing there? Part of what drives so much anxiety, confusion, and conflict may be that what we are hoping to achieve on social media is too broad, too vague, and too all-encompassing. Those accounts which tend to be the most productive and interesting (in my experience) are those focused on a particular set of issues, goals, and objectives. But what these platforms want us to eventually want, by their nature, is everything. So we are always on the horizon for expansion, which makes every other account a potential model and potential rival.

Major changes are coming for the current prevailing social media platforms. With the movement towards Meta, Mark Zuckerberg hopes that his tech enterprise will pervade more and more of our lives. With his purchase of Twitter, Elon Musk hopes to generate more profit for the company while limiting the rules, boundaries, and norms of social intercourse as far as possible. What we are seeing here are changes similar to that of Zappos, with Facebook moving away from a mission focused on a particular focus and seeking to occupy more general spaces in our lives, and Twitter poised to drive rules and hierarchies underground, all of this likely generating anxiety, chaos, confusion, and conflict.

Hopes nonetheless

The dynamics of the social media incentive structure are subtle and seductive. They are activated in surprising ways, and built to protect the structure over any individual users (or group of users). I don’t really know what to do with this. For now, I’ve chosen to scale back. Over the next year, I'll likely be trying different ways to reenter various social media spaces in a way that is healthier, more dynamic, and more creative.

Not all mimetic desire is bad. Girard looks to Shakespeare, in many ways, as the literary genius of mimesis. Girard locates mimetic desire as a key theme and focus across his plays. The rivalries and conflicts of mimesis don’t have to be unqualifiedly and universally destructive. They can be light, funny, and transformative, as well. Girard writes of Shakespeare, “He has his own inimitable style of theorizing mimesis: discreet, even covert at times—but hilariously evident and comical as soon as we possess the key that opens all the locks in this domain.”

There is another way to tell the story I have given so far, one that might be more self-deprecatingly funny, more embarrassing but also lighter, more critical but also bending more brightly towards hope. I don’t know yet how to tell this story. But I do believe that it can come. One thing I learned in the course of writing the first draft of my memoir is that the stories we tell are always the stories we tell for the time that they are told. The story I’m telling of my conflict with Maria is the story of today. Tomorrow I will have a different story to tell of that time. I hope it will be a better story. Today perhaps it is Macbeth. Perhaps tomorrow we will wake up and discover it was A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This is a key lesson I’ve learned from various hardships: we often think our life is a tragedy, but if we keep going forward, we can often find a comedic turn like a bend in the road.

III. Mimesis and social media: potential solutions

Possible ways forward

As I begin engaging again on social media, I've considered new ways to frame my approach, and also to try resisting the pull of toxic forms of mimesis. When we engage in social media, we are not engaging in a world of neutrality, but in a structure designed to seek and support certain ends by particular means. The need to work actively against some of these is like the need to engage in active antiracism: if you don't actively work against the tendency towards harms, the system will pull you in to (unwittingly) becoming part of them.

1. Acknowledge influences.

If there’s one key takeaway from Burgis’s book, it is this: we all live in an economy of desire. None of us is an island. We influence and are influenced, which is to say, we are human. Girard writes of A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

“Shakespeare satirizes a society of would-be individualists completely enslaved to one another. He is mocking a desire that always seeks to differentiate and distinguish itself through the imitation of someone else but always achieves the opposite result.”

Girard’s point is that, in the play, the characters think that their desires are manifestations of their “authentic” individual persons, when in reality they are always, without realizing it, operating off of what someone else has given to them, which makes them more like one another and drives conflict. This is mimesis. This is what we all do. This is the satire that social media similarly creates.

In the context of social media, we must accept the fact that we are both influence and influenced. The latter is especially important. We need to give up the idea that we can resist being influenced by our feeds. Instead, we should come to a better understanding of what constitutes our feeds, and a greater awareness of how it impacts us. The first step in changing reality is to recognize it for what it is. As Girard further writes, “differentialism is the ideology of the mimetic urge at its most comically self-defeating,” and, “The more mimetic we are, the less we perceive the mimetic law that governs our behavior as well as our language.” To see reality, we must see how our desires are not just our own. The less we are able to admit this, the less we are able to see.

For Catholics, the practice of Eucharistic adoration helps us know how we don’t just consume with our mouths. We consume with our eyes as well. Observation is transformative, whether we want to admit it or not. If we can admit it, then we can start to make intentional choices about how we are transformed.

2. Reframe success, being attentive to the pervasiveness of certain numbers.

Social media platforms drive our images of success through their use of numbers: number of followers, number of likes, number of shares, number of views, etc. Social media platforms have no way to measure depth, and can only provide us engagement counts. As I mentioned earlier, these are measures of imitation or modeling, and so they present significant dangers for those wanting to resist mimetic rivalries.

We should be cautious when considering comment counts as measures of success. Quite often, comments are not deep engagement, but are rather practices of mimesis. This can be especially clear when one imagines having all those who have commented on a post sitting together in a living room. If we were all in a room together, and each of the successive comments were the comments made in a conversation, would the conversation be one in which there is no development, and where the comments are repetitive reactions rather than personal and developmental responses to the original statement? Rather than real dialogue, social media platforms more often elicit emotional reactions put into words. Such responses are not inherently bad. But they can evidence or contribute to the shallow and toxic dynamics prevalent on these platforms.

We cannot escape the ways in which platforms drive us to focus on “engagement” counts. But we can consistently remind ourselves to resist them, and to seek out other measures of success. For example, we can focus on and seek to capture for ourselves the extent to which our platforms foster conversations that open up new ideas, bring to light new resources for learning and growing, transform the way that we live and work and relate to those in our offline lives, and create connections that extend beyond the platforms. Social media platforms are very powerful, and they are full of promise. (Twitter, for example, has played an essential role in supporting Ukraine’s defense against Russian misinformation, and some have likened Instagram infographics to W.E.B. Du Bois’s data portraits.) But we can only reap the full benefits if we are attentive to accompanying risks and dangers.

3. Cultivate better model relationships.

One possible solution might be working towards a smaller world of Freshmanistan and focusing on cultivating better (and more remote) models. Resisting the overly flat structures of social media, making clearer hidden hierarchies and embracing them where helpful, may aid with this. This is especially important for those seeking to use their platforms towards social change. Odell notes how the most successful social change movements have been those with federated relationships and complex hierarchies. Flat structures breed chaos and confusion, and often function to hide hierarchies rather than to eliminate them. One must be attentive to the dangers of various forms of hierarchy. But history suggests that overcoming hierarchy altogether is a false dream with catastrophic consequences.

Celebristan relationships are not necessarily bad. Burgis suggests they are inescapable. In many ways, they are preferable to Freshmanistan relationships. At times they can be very helpful. And so part of developing a better relationship to desire involves cultivating better Celebristan relationships, which includes cultivating better models. The first step in this process might, again, be making explicit the hidden hierarchies and models of desire in our social media worlds, and considering whether we have situated ourselves in a web of relationships conducive to healthy cycles of desire. We can work on developing approaches and practices which might inhibit unhealthy cycles, and then seek to identify healthy models to bring into that web of relationships to cultivate healthy hierarchies for ourselves.

4. Depersonalize, and embrace limited models.

Another way to resist harmful mimesis might be to make our social media accounts less personal. Consider again what Burgis had to say about good leaders when it comes to mimesis: good leaders help others expand their world of desires, while also shifting the center of gravity of desire away from themselves. On social media, those of us who manage "platforms" might do well to make them less "personal" and more mission-driven or goal-oriented. It may be healthier to treat a social media account more directly as a mission-focused "brand" and less a space of "sharing the real you." Of course, honesty and openness are good and valuable. But transparency itself is not a virtue, and certain forms of "transparency" can serve to hide or obscure deeper truths. Transparency should be in the service of something else.

The increasing "personalization" of social media and cultural controversies helps drive the necessity of "cancelling" others. To the extent that we must imitate or oppose (via mirrored imitation) a model, we must engage in either wholesale support or wholesale condemnation of the model. If the mimetic center of gravity is on one model, then we are driven to relate to the model in a black-and-white way. There is less space to see and appreciate others as limited models, to embrace others as only partial models, as models in some ways but not others.

We can observe the transition from pursuing a goal to engaging in a mimetic rivalry in certain areas of antiracism. There are certain places where a transition seems to occur from eradicating racism to eradicating racists, or at least shaming, silencing, and isolating them (all practice which can orient towards eradication). (Fighting racism and fighting racists are not the same thing, and they may often be at odds with one another.) This includes not only those who refuse to acknowledge that racism exists, or who actively pursue racist agendas, but also those who engage in good faith to try to understand and address racism, but who don’t do it in a way that certain activists believe is correct. This is a shift from the pursuit of social justice to a mimetic rivalry. This, I believe, is part of what happened between Maria and Nicole. Because of certain perceived race-related failures of Nicole on the part of Maria, Nicole became a generalized problem. Nicole became a model read in her entirely through a particular lens, and that became a black-and-white problem.

To the extent, however, that we can resist the drive to treat others as totalized models, then we can start to appreciate others as complex beings, recognizing their limitations, appreciating their virtues, and allowing for their mysterious humanity. And if we can appreciate individual platforms as focused on particular issues, problems, or goals, rather than as focused primarily on a person, then we can appreciate the limitations of models and create space for the complexity of human life.

5. Diversify the models we present.

For most of us, our social media accounts center on one model of desire: ourselves. Even when we aren’t necessarily posting photos of ourselves, when we present personally-branded messages, we are presenting ourselves as the model to desire a message or goal or outcome. This can help drive unhealthy mimetic relationships, as it can draw too much of a center of gravity to ourselves.

One way to change these dynamics is to intentionally diversify the models presented on our accounts. Who do we see as good models of various kinds of desire, and how can we present them as potential models to our own followers? This is similar to much of the above, shifting the center of mimesis’s gravitational pull away from ourselves and letting it rest in a way that is much more spread out.

6. Practice empathy in the face of victimization.

Burgis also emphasizes the centrality of empathy in overcoming toxic mimesis. Empathy, he argues, is anti-mimetic, because while sympathy tends to come from an identification with the other and an adoption of their emotions, empathy allows one to enter the experiences of another while maintaining individuality and emotional autonomy. (Burgis defines the distinction between empathy and sympathy somewhat differently from others, such as Brené Brown; for the purpose of this essay I will use Burgis’s understanding of the two.) Empathy is a virtue that hinges upon the ability to exert boundaries in one's emotional life and to maintain one's role in the face of another's suffering.

Sympathy is a much easier and more common response to the suffering of others, and the emotional response which pervades social media. It is most emblematic in the retweet or verbatim resharing of emotionally-charged content, because these are essentially practices of mimesis, of copying the pathos of a model. Because empathy requires consideration, connection with the experience of another, and then a reframing of that experience appropriate to one’s specific role of support, its practice is much more difficult in those spaces.

Empathy is central to many professions. My past volunteer work as an immigration attorney required me to relate to my clients on an emotional level and create a space where they would feel seen and heard as full persons with complex emotions. I needed to connect to their emotions to serve them well. However, I also needed an emotional boundary between my clients and myself, so that I wouldn't be overcome by the emotions of their stories and so that I could maintain my role as supportive professional. Relating too much to them could undermine my ability to support them in the way they needed to be supported.

Receiving the difficult stories of others has helped also me understand the complex relationship between victimizing, victimhood, and the role of a support professional. In my immigration work, I had represented people whose stories ranged from children fleeing their home countries after most of their extended family had been murdered by gangs, to a man around my age who had escaped civil war as a child (after watching much of his family being brutally murdered), who never seemed to really escape his demons, who was facing deportation after participating in the trafficking of a minor in this country, and who would likely face death in his home country if deported. In supporting clients like the latter, I’ve learned that “perpetrator” is almost never a person’s sole identity. Usually, “perpetrator” is supported by an earlier experience of horrific victimhood. (Again, this highlights the ways in which failing to reorient one’s relationship to past victimhood can cause significant harms down the road.) I've learned that there is a story behind the story behind the story. I've learned that hurt people hurt people. I am trying to keep this mind when I experience myself as a victim of others in various circumstances.

If sympathy towards a victimizer tends to excuse their harmful behavior because it gets so caught up in the emotional experience of the victimizer, empathy allows one to feel sorrow for the events leading up to the victimizer’s harmful actions while also expecting accountability for and not excusing those actions. Coming to see the humanity of a victimizer (which includes not seeing them as solely a victimizer) while acknowledging that harm has occurred and must be recognized and accounted for is an achievement of empathy, one which empowers the victim and can help everyone step out of various forms of toxic mimesis.

7. Create boundaries.

Burgis recommends creating boundaries with unhealthy models. He gives the example of a friend (we’ll call him Josh) who got caught up on a mimetic relationship with a coworker, who he calls Tony. Josh was constantly aware of whether Tony seemed to be working longer hours, getting more professional opportunities, and engaging in certain behaviors (such as investing in Bitcoin). Josh would do these as well, but try to do it "more." Years after they had stopped working together, Burgis came across an article profiling Tony and sent it to Josh. Josh responded:

"Thanks for sending me this. I deleted it immediately. About a year ago, I completely untethered myself from Tony to the point where I no longer even know what he's up to, and I'd like to keep it that way. Someday, once my rivalry with him runs out of oxygen and dies, I might not mind. But for now, I'm starving it to death. Can you do me a favor and not send me stuff like this?"

Josh realized that this old coworker had exerted a gravitational pull on him that led to negative cycles of desire. And Josh, being aware of his own limitations, recognized that the best way out was to set up firm boundaries. At times, you may need to ask your friends to help with them.

Looking back on my conflict with Maria, I now realize that I would have benefitted from setting boundaries with my followers. Undoubtedly, they were trying to be helpful, making me aware of little jabs that continued to be made against me. Others were reaching out, at times, in search of support, after being subject themselves to similar behavior by Maria and others and trying to make sense of it. Perhaps in another situation I could have offered this help and received these messages in a healthy way. But, looking back, I see how I was still caught up in the gravitational pull of a mimetic rivalry, and awareness of Maria’s behavior wasn't helping me.

A part of me wanted to stay aware of harmful behavior so I could continue to support others, but I needed to follow the airplane mask rule: make sure you have the mask pulled over your face before you assist others. I couldn't save others from what I was still really struggling through myself. Trying to save others put me too much at risk of losing myself and magnifying the harm to everyone. Maybe one day I can offer more help to others through that, but for now I need to tread lightly, slowly, and very intentionally through this.

Another part of me struggled with the unfairness of it. Why did I need to be the one to step away, to be “the bigger person”? Was I just letting myself get bullied out of that space by Maria, her friends, and her followers? Of course, focusing on “fairness” can cause us to lose sight of the actual problems and real solutions. I could complain about what was “fair,” or I could do what I needed to do so that I could stay sane and work towards my own growth and development. Much of life consists of that choice. There isn’t a “fair” choice here. But there is a right choice.

8. Practice empathy in the form of “Fulfillment Stories” and mantras of hope for others.

In pursuing positive cycles of desire, one practice of empathy that Burgis recommends is the sharing of "Fulfillment Stories." These are stories consisting of (a) an action one took, (b) which one believes one did well, and (c) which brought a sense of fulfillment. Burgis writes:

"The more we understand one another's stories of meaningful achievement, the more effectively we understand how to work with each other: what moves and motivates others, what gives them satisfaction in their work... Ask yourself: How many people do you work with who could name even one of your most meaningful achievements and explain why it was so meaningful to you?"

Knowing these stories help us to enter into the experiences of others and consider how we can contribute to their positive cycles of desire. They also help us to see others' positive movements of desire as potential creative models for ourselves.

For those we relate to as mimetic rivals, various practices of empathy can help us resist toxic mimesis. It's important to note that resistance must occur through practices of empathy. We must work actively against mimetic forces (including, at times, sympathy) to see the emotional lives of others, to see others as beings with complex emotional beings just as we are. And we must seek to disrupt toxic cycles for both of us.

One practice recommended to me recently was to speak a positive mantra when I feel mimetic forces arising around certain people. For one person, when I feel the rise of mimetic rivalry, I try to speak, "[Name,] I wish you healing." In the end, what I hope for everyone in all of these disputes is that we will be able to find healing, wholeness, and new ways of engaging one another. This is one of the challenges of being a Christian: holding on to hope for things we cannot imagine today. This is part of the hope for Christ as a mimetic model: that he will expand our desires to want things we did not know we could want. I don't know what healing, reconciliation, and wholeness will look like exactly. But if I look to Christ as my model, I know that the pathway towards them will be fucking weird.

IV. The end

Consumption of the rival

Consider again the accusation of engaging in "turf wars."At this point, the conflict is no longer over competing approaches to antiracism or deconstruction or over the acceptability of particular behaviors. When this becomes the key focus, we have moved away from discussing particular issues and, instead, have focused on the issue of desire. What is being critiqued is not any particular idea or action, but the desires of a model (whether directly mimetic or mirrored), and soon the model themself.

Thus Girard writes in an essay on A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “As our mediators prevent us from possessing the object that they designate to us, we prize the designated objects more and more, but this is true only in a first phase; when the rivalry further intensifies, the object recedes into the background and the mediator looms larger and larger.” As I engaged with Maria and others during that most immediate time of conflict, what I failed to realize at the time was that this wasn't so much a conflict over antiracism as it was becoming a conflict over desires to occupy certain spaces to the exclusion of others, and then over the people involved in the conflict themselves. This is partly why the focus could never land on addressing particular ideas or behaviors but, instead, focused on motivations and the character of various persons.

Girard also writes, “The object is only a means of reaching the mediator. The desire is aimed at the mediator’s being’… [H]owever desirable the object may be, it pales in comparison with the model who gives it its value.” In a mimetic rivalry, one turns from seeking after the object of the rival competitively to seeking to consume and become the rival themself. The becoming is never perfect, however. Girard writes in another essay on the ways in which mimetic conflict tends to merge the rivals: “Entities are beginning to merge that will never truly belong together; the result is a jumble of bits and pieces borrowed from the component beings.” When the process is complete, and one rival has won, that winning rival does not become the consumed rival in a pure way. Rather, the winning rival becomes a jumbled shape of pieces collected over the course of the rivalry. Girard further writes:

“Mimetic desire really works, in other words; it truly achieves the goal of personal metamorphosis that it had set for itself, but in a self-defeating fashion. The lovers [of A Midsummer Night’s Dream] are really transformed into one another but not in the manner that they had hoped; they feel surrounded by moral and even physical monsters, and turn into monsters themselves. As with the bad sisters in the fairy tale, their wish is fulfilled, but in such a way that, had they known the final outcome, they would have made a different wish.”

In a mimetic rivalry, to win is to lose. But this rivalry changes us to such a degree that we may not be able to recognize this. Many times, our consequent misery becomes our consolation, a twisted form of comfort and self-assurance.

If Girard is right, then one might find the climax of that conflict between Maria and Nicole, not just in Nicole shutting down her Instagram account and leaving behind her platform, but in Maria subsequently participating in a live event with her friends on deconstruction, a central subject of Nicole’s account. Read through the lens of mimetic theory, that event takes on much more significance and becomes much more interesting. In that live event, one thing Maria was doing was becoming the model that she had sought to defeat, stepping into the shoes left behind by Nicole. She consumed parts of her rival and assimilated them into her own public being.

Mimetic rivalry would help explain subsequent behaviors as well. If Girard is right, and such a rivalry gives an explanation of the conflict, then that originally fought-over object (the subject of deconstruction) would be of waning interest to Maria as the conflict receded, with Nicole no longer to serve as mimetic rival and model. Without a rival (Nicole), that original object (deconstruction) loses its desirability. The parts of Nicole which were consumed into the new public mass would shrink, as if the rivalry had caused an inflamed swelling of those assimilated parts of the rival and, without active conflict touching them, they were shrinking back down. The winning rival, if habituated into rivalry, will go off in search of the next model, find the next place of proximity, begin the next pursuit of mimetic rivalry and consumption.

The repetition of rivalry

The more we get into mimetic rivalries, the more we tend to see potential mimetic rivalries, and the more we tend to get into mimetic rivalries. That is, the more we get into them, the more likely we are to facilitate them. In his recently published book Us: Getting Past You & Me to Build a More Loving Relationship, relational life therapist Terrence Real writes, "I believe there's no such thing as overreacting; it's just that what someone is reacting to may no longer be what's in front of them." We tend to see what we have seen before, and part of the challenge of life is learning to adopt a vision for the present.

Consider a couple, Sarah and Ben. When Ben tells Sarah that he would like for them to have more sex, Sarah immediately responds with rage, yelling at Ben and screaming that he needs to respect her boundaries boundaries. Part of Sarah’s history includes sexual violence perpetrated by a past partner whose misogyny had included sexual entitlement. She was able to escape that relationship when she finally asserted herself against that partner’s entitlement. Ben is a gentle partner who wants to respect Sarah’s autonomy and engage in sex only with full consent. But even gentle requests makes Sarah’s past relationship come alive for her, and she responds to Ben’s requests as if he were that entitled partner.

When considering a couple like Sarah and Ben, Terrence Real’s argument makes two points. First, Sarah’s volatility and rage make sense from the perspective of her history. She is responding from what she has learned she needs to do to survive. She is responding in a right way, but to the wrong situation. A response of sympathy (as understood by Burgis) would simply let Sarah’s furious rage continue unquestioned, would allow it to continue to occupy space. But Real helps us create emotional boundaries with a second point, emphasizing that the volatile response from Sarah, while rooted in a valid reality (the reality being triggered), is not grounded in the reality of today. Relating well to one another means seeking ways to live in the present reality together and to not get pulled into a past reality of emotional volatility, thus extending it. This, of course, takes time and effort. But it is the pathway towards healed and whole relationship. If the person triggered cannot come to a grounded relationship in the present reality, good boundaries are especially important.

Real writes:

“Am I talking to the mature part of you, the one who’s present in the here and now?... Or am I speaking to a triggered part of you, to your adversarial you and me consciousness? The triggered part of you sees things through the prism of the past… One of the blessings that partners in intimate relationships bestow upon each other is the simple and healing gift of their presence. But in order to be present with your partners, you must yourself be in your present, not saturated by your past.”

In the context of mimetic rivalry, persons who have a tendency to get into rivalrous relationships will tend to see them everywhere. The tendency to get into mimetic rivalries doesn’t end until it is disrupted. When rivalries (or even just potential rivalries) are perceived (whether or not real), they are triggered, and this is often how they begin. When engaging in conflict or high tension situations, it's important to recognize when a rivalry is being triggered, to see when the argument is no longer about a particular matter and becomes just about arguing (or about the rivalry itself, in some other way), and to work to come to a different relationship to one another or to establish boundaries if you can't come out of it.

The scapegoat

Of course, this extended essay makes the moves of a mimetic rival, in a way. It has moved away from the original topic at issue (divergent approaches to deconstruction and antiracism and particular harmful behaviors) and sought to explore the psychological dynamics beneath the conflict which arose, looking more at the model(s) than the topics which had given rise to the rivalry. To the extent that the perceived “Maria” holds a place as a central character in this essay, she is a key model for it, and may continue to hold sway as a potential (or actual) rival.

I should also acknowledge that there is something unfair about this essay, in that it considers dynamics involving a person who has taken no part in writing it. And thus the “Maria” of this essay is not truly a real person but is rather a considered idea based on a list of interactions. However “fairly” this essay has tried to consider Maria, the reality of a person always goes well beyond the words written about them. The Maria of reality will always, in some way, defy the “Maria” put into words. Instagram allows only a limited presentation of personhood, and so do essays. (Plato has warned about the limitations and dangers of writing.) I occasionally think of the words of the adulterous husband in The Good Wife to his wife after they have had a sort of reconciling: “I’ve never been as bad as you wanted me to be.” Mimesis doesn’t always cause us to idolize our models by making them too great; we might idolize by making them too bad. As a participant in the rivalry myself, I may be doing both here.