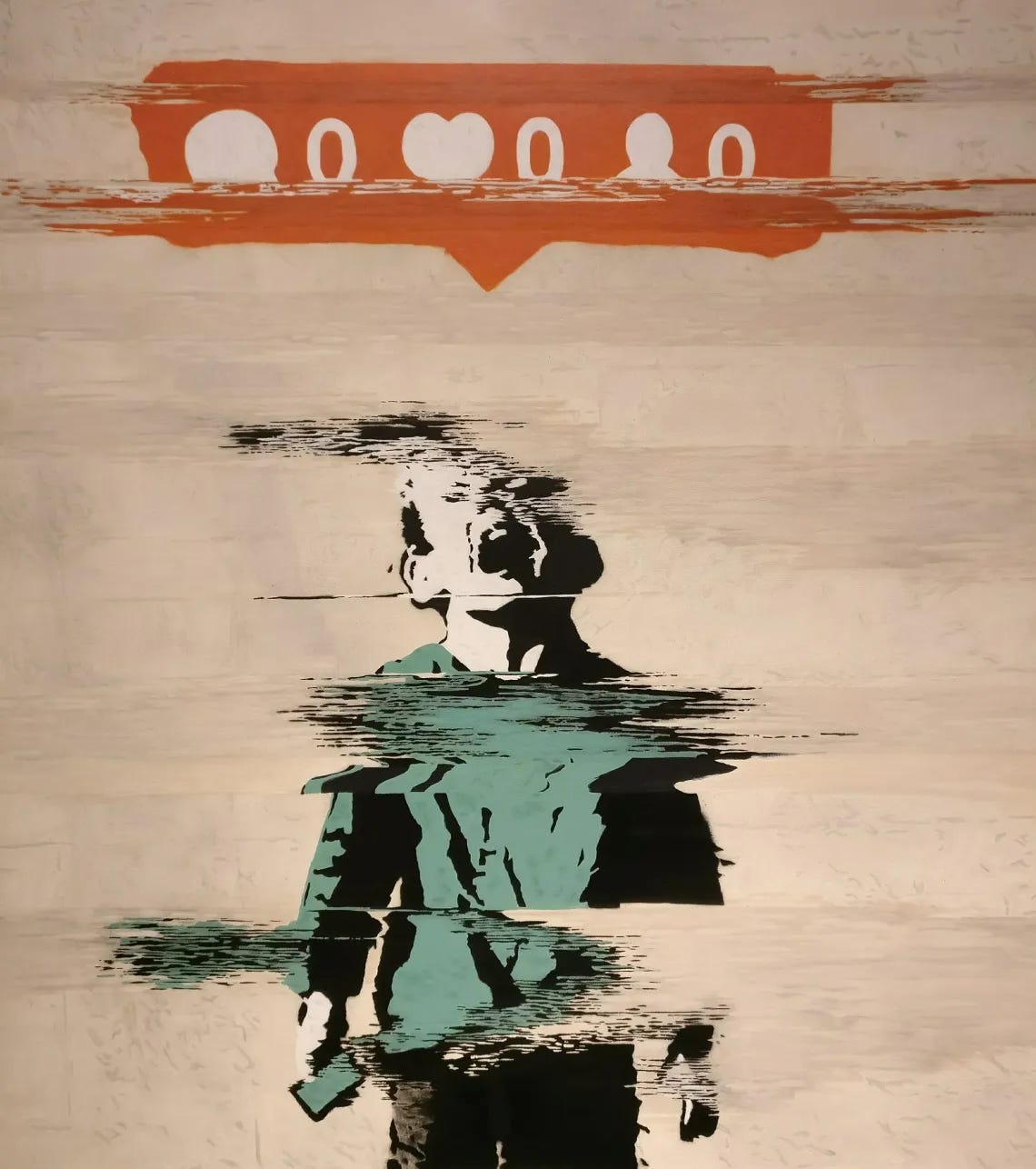

Newsletter #26: the end of social media

In this newsletter: my changing approach to social media, Substack's chat feature, the end of the social media age, and more

Happy Tuesday! Here’s what’s in the newsletter today:

Social media: from centralization to federation

My social media accounts

Substack has a new chat feature

Brief thoughts

What I’m reading: the age of social media is ending

What I’m reading: Anthony Veasna So’s Afterparties

Social media: from centralization to federation

How to do Nothing has helped me to explore ways to reform our use of social media and networking, fostering better connection and enabling more meaningful engagement. Odell believes this can be done within existing platforms, but not in the ways driven by the designs of the most popular. Odell emphasizes how “meaningful ideas require incubation time and space,” and she proposes alternative platforms to the prevailing giants such as Twitter and Facebook (as well its subsidiary Instagram). She looks “both to noncommercial decentralized networks” such as Mastodon and Scuttlebutt and “the continued importance of private communication and in-person meetings.”

Odell focuses on the need for meaningful social dialogue and change. In contrast to spaces created by Facebook and Twitter, she emphasizes how the history of collective action (“from artistic movements to political activism”) involved a diverse set of federated spaces. Small groups would engage in directional debate and disagreement, and these groups would keep in touch with other groups, establishing various networks. Mastadon and other platforms create such smaller groups, whereas the prevailing giants drive and are built to foster open conversation at a large (global) scale. (Though she doesn’t discuss this at length, it’s interesting that Twitter and Facebook operate with the illusion of a flat structure, in contrast to the visible complex hierarchies of other federated spaces.)

Bringing conversations out of open global spaces and into smaller decentralized spaces will not inhibit meaningful dialogue and real change. Odell writes that history suggests the opposite. Odell draws on “Arendt’s observation that dividing power does not decrease it, and that its plural interplay increases it.” Arendt’s observations in On Revolution suggest this may be close to the natural inclinations of humankind in the world. She writes:

“For in America the armed uprising of the colonies and the Declaration of Independence had been followed by a spontaneous outbreak of constitution-making in all thirteen colonies… so that there existed no gap, no hiatus, hardly a breathing spell between the war of liberation, the fight for independence which was the condition for freedom, and the constitution of the new states.”

The history of the United States, according to Arendt, challenges a Hobbesian view of the “state of nature.” When a vacuum was left with the absence of colonial rule, the people in the colonies began to organize themselves. Local councils formed, comprised of those who cared for this kind of work and who had initiative to take it upon themselves. Representatives from federated councils would convene to form another layer of the political economy, and in this way a pyramid structure formed. The interesting thing about this structure is that “in this case authority would have been generated neither at the top nor at the bottom, but on each of the pyramid’s layers.”

Prior to my recent break from my public-facing social media accounts, I had started moving in a direction of building webs of relationships where, if I am removed, the webs remain intact; they might be strengthened by my presence but will remain in place without it. For example, a couple of months ago I had invited my Instagram followers to tell me what sorts of people they’d like to meet and spaces they’d like to see, and then followed up with an online form to sign up for such spaces. I then created group chats for those who signed up and left the chats so that the participants could own and drive those conversations.

What Odell (as well as Arendt) had offered me is an alternative approach to social networks and media, an approach which goes directly against the online engagement machine. People want this. Hundreds of individuals asked to participate, and I set up dozens of chats, leaving the vast majority of them myself. Some chats took off before I departed, and some began and quickly fizzled out. At the very least, those who participated were able to connect with others who had interests in spaces dedicated to things like Catholics “with atheist partners,” “feminist stay at home moms who don’t want to have 10 kids,” Catholicism and unplanned pregnancies, “parents with special needs kids,” and “queer POC people who are trying to have healthier boundaries with Church stuff.” I’m hoping that some of these conversations will make their way into other spaces, and this is likely already happening. Less than twenty-four hours after I began this exercise, one participant reached out to me to share that through one of the chats she had met someone from her city, and they planned to meet in person.

My social media accounts

Many of you have noticed that I’ve deactivated some of my public-facing social media accounts, and that I haven’t been active on any of them recently. I may write more about this later, but what I’ll share for now is that deprioritizing those spaces has felt good in many ways, and it feels right. I’ll be exploring other spaces while I continue to process the role that social media has in my life. Coincidentally, Substack recently rolled out a new chat feature…

Substack has a new chat feature

At the beginning of the month Substack introduced Chat, a new space for writers to host conversations with their subscribers. Some writers have announced that now “Elon Musk isn’t the only guy who can run a Social Media company.” Substack discovered that many writers were developing offshoots to their writing platform, drawing readers to other platforms to enable conversation and connection. So this space (still early in development) is meant to tie that conversation to Substack itself, in a more easily manageable way.

For now, I’m going to pilot the chat feature here to bring you along while I read interesting books or do things like visit art galleries. It’ll be limited to paid subscribers (to limit trolls and the amount of management required), though if I decide to make Substack Chat a longterm part of this Substack I may explore other ways to verify and add users who aren’t paying subscribers.

To join the chat, you’ll need to download the Substack app (messages are sent via the app, not email). And you can turn on push notifications to stay up to date.

How to get started:

Download the app by clicking this link.

Open the app and tap the Chat icon. It looks like two bubbles in the bottom bar, and you’ll see a row for my chat inside.

That’s it! Jump into my thread to say hi, and if you have any issues, check out Substack’s FAQ.

Brief thoughts

In lieu of tweeting, here are some brief thoughts I’ve collected recently…

A friend’s thoughts on finally dating a man who’s not a religious zealot: “Religion is not an obstacle in his personality, I’ll just say. With a lot of people here (in our local uber-Catholic community), you can physically see them struggling. They are physically hanging on by a thread.”

Being off of social media for several weeks has helped me realize how so much of (Catholic) social media is about making sure I’m aware of all the things I should feel guilty for.

I recently opened Tik Tok, and it was just too much. First was a video where a woman was crying and walking around her destroyed home. Next was a cute kid. Then a prank video. If you scroll Tik Tok and don’t feel emotional whiplash, should that be concerning?

In a 2015 interview, Pope Francis was asked who he was. He said, “I am a sinner … I am sure of this. I am a sinner whom the Lord looked upon with mercy.” I feel this as well. I am one whom the Lord looked upon with mercy. But not only that. I have been looked upon with mercy by friends. Only, they didn’t call it mercy. They called it friendship. They called it, “I love you.”

Midnights is actually an album about religious deconstruction and reconstruction.

What does it actually mean to be a “heretic”? I thought I had a good grasp on this, but now I’m suspecting that the prevailing definitions are more self-serving than (ironically) “orthodox.” I wonder whether it is really more of a functional, rather than meaningful, term, something that operates to control and bound and enforce, rather than to enlighten and clarify.

What I’m reading: The Age of Social Media is Ending

Ian Bogost in The Atlantic recently wrote about how the age of social media may be coming to an end. Users on major platforms like Facebook and Twitter are departing. Twitter is seeing large advertisers (the platform’s primary source of income) contemplate stepping away. And continued studies on the harms of social media, combined with legal and regulatory developments, may make the maintenance of these platforms too unwieldy, unpredictable, and complicated.

I’d recommend reading the article in full. But here are some notable excerpts:

“Today, people refer to all of these services and more as ‘social media,’ a name so familiar that it has ceased to bear meaning. But two decades ago, that term didn’t exist. Many of these sites framed themselves as a part of a ‘web 2.0’ revolution in ‘user-generated content’… But at the time, and for years, these offerings were framed as social networks or, more often, social-network services...

As the original name suggested, social networking involved connecting, not publishing. By connecting your personal network of trusted contacts (or “strong ties,” as sociologists call them) to others’ such networks (via “weak ties”), you could surface a larger network of trusted contacts… The whole idea of social networks was networking: building or deepening relationships, mostly with people you knew. How and why that deepening happened was largely left to the users to decide.

That changed when social networking became social media around 2009, between the introduction of the smartphone and the launch of Instagram. Instead of connection—forging latent ties to people and organizations we would mostly ignore—social media offered platforms through which people could publish content as widely as possible, well beyond their networks of immediate contacts. Social media turned you, me, and everyone into broadcasters (if aspirational ones). The results have been disastrous but also highly pleasurable, not to mention massively profitable—a catastrophic combination.

…

In their latest phase, their social-networking aspects have been pushed deep into the background. Although you can connect the app to your contacts and follow specific users, on TikTok, you are more likely to simply plug into a continuous flow of video content that has oozed to the surface via algorithm. You still have to connect with other users to use some of these services’ features. But connection as a primary purpose has declined. Think of the change like this: In the social-networking era, the connections were essential, driving both content creation and consumption. But the social-media era seeks the thinnest, most soluble connections possible, just enough to allow the content to flow.

…

On social media, everyone believes that anyone to whom they have access owes them an audience: a writer who posted a take, a celebrity who announced a project, a pretty girl just trying to live her life, that anon who said something afflictive. When network connections become activated for any reason or no reason, then every connection seems worthy of traversing.

That was a terrible idea. As I’ve written before on this subject, people just aren’t meant to talk to one another this much. They shouldn’t have that much to say, they shouldn’t expect to receive such a large audience for that expression, and they shouldn’t suppose a right to comment or rejoinder for every thought or notion either. From being asked to review every product you buy to believing that every tweet or Instagram image warrants likes or comments or follows, social media produced a positively unhinged, sociopathic rendition of human sociality. That’s no surprise, I guess, given that the model was forged in the fires of Big Tech companies such as Facebook, where sociopathy is a design philosophy…

Again, I’d recommend reading Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing.

And a few other articles that may be of interest:

Some of my thoughts on the value of private (vs public) accounts

Looking to leave Twitter? Here are the social networks seeing new users now

Twitter has lost 50 of its top 100 advertisers since Elon Musk took over, report says

What I’m reading: Anthony Veasna So’s Afterparties

Last week I wrote about one of the short stories in the posthumously published Afterparties by Anthony Veasna So. I couldn’t recommend the collection enough. You can read a bit about it here.

You can follow along with my current reads at Goodreads.

Now accepting submissions!

If you like what I’m doing here and want to join in this developing project, I’d love for you to submit an essay, poems, or a short story for consideration. You can learn more here.

Follow Along

And that’s all I have for you today. If you’re on social media, you’re welcome to also follow me at Twitter and on my Facebook page.

“I have been looked upon with mercy by friends. Only, they didn’t call it mercy. They called it friendship. They called it, ‘I love you.’” All teared up! Beautiful Chris.