This piece is part of a series addressed to family and friends, looking at current political and social issues from the perspective of my studies and experiences. You can read the last part of this series here.

CW: drugs, HIV/AIDS, death, school shooting, homophobia.

Dear Family and Friends,

I got a new doctor this year. I used to see this nice old man in Saint Paul that I thought was a pediatrician after he asked me if I wanted to hear my heartbeat and showed me where my kidneys were. Super nice guy. But when he gave me my PreP prescription, I asked him how long I should wait to have sex, and he said, "I'm not sure. Let me check."

I decided it was time for me to see someone who had expertise working with LGBTQ people.

The new doctor was a cutie in South Minneapolis. We talked openly about my lifestyle. Near the end of our visit, I said, "So I have a question. And maybe it's kind of a silly question. But I just wanted to ask it."

"Sure!" he said.

"So... coke is a bad idea, right?"

He smiled. I felt that he wanted to laugh. It was probably because of how I asked the question. Like I knew it was a silly question. But I just needed to ask it.

"Yes," he said. "I'd say it's a bad idea." He then talked through the risks of cocaine and said it was a higher risk drug, compared to drugs like ecstasy or ketamine.

"Oh," I said. "So ecstacy and ketamine are fine, then?" I was half-kidding.

"Ok, I can't say that," he said. "But they're lower risk than cocaine. There's still risk involved. But lower risk."

I'm not someone naturally inclined towards drugs. I know a few people who almost died from bad coke, and one person who did. I had been around people using recreational drugs, and I wanted to be smart about my choices. Hearing my new doctor talk through the risks in a non-judgmental way helped me confirm that coke is probably not for me.

At the end of our appointment, he took me over to get my labs done by this perky older lady with an Eastern European accent. I thought about asking for juice, but this lady was quick with the blood draw.

A couple of days later, my results were back. Negative for everything. But something weird came up.

Slightly elevated triglycerides. Slightly elevated A1C. Indicating pre-diabetic. Wtf.

Cutie South Minneapolis gay doctor recommended increased regular aerobic activity, aiming for "30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise at least 5 times per week." He recommended eating "more healthy, unsaturated fats from foods like walnuts, flax seeds, and avocados."

I was pissed. Here's the thing. I have a very well-balanced diet. I exercise 60-90 minutes, 4-5 times a week. I do it partly for vanity and partly for my mental and physical health.

That should be enough. I don't do much running. I hate running. Because running is of the devil. Do you know what happened to the first man who ran a marathon? He DIED. People often forget that. The human knees were not made for marathons. I don't respect people for doing marathons, because I have a respect for God's gift of human knees.

I was also scared.

Christmas

I had been shaped over the last year, in a number of ways, by death. On Christmas Eve, we found out that a very close family friend had passed away in her sleep. She was in her early sixties and had many dreams for her years ahead. My Christmas present from her was in her car, ready to be taken to the post office.

She was diabetic.

The day she died, something had been off. She was supposed to meet her father for Christmas Eve, but she didn't show up. My mother got looped in. Mom knew something wasn't right. She had a neighbor of the family friend call the police, telling them to break down her door.

They found her in her bed. She had had a diabetic episode and didn't have enough consciousness to take insulin, even as her alarm was going off. So she drifted off and died.

If she'd had her insulin, she would have woken up as if it were any other day. She would have met her father for Christmas. She would have put my gift in the mail. She could have had years and years and years of life.

But she didn't. She died. We were all so sad.

And I was scared.

I played scenarios in my head. I was single. I lived alone. What if I was diabetic and had an episode and didn't have the wherewithal to take insulin and no one home to help me and I died at 33?

I started thinking about Catholicism. I thought about my earlier life, when I had really wanted to live by "the rules," to be a good celibate gay Catholic boy. This wasn't one of the things the Church had thought about when her leaders insisted that gay people be single and celibate and not live with women or other men we could be attracted to. The advice that I got from most "orthodox" Church leaders was that we should only live with unattractive straight men until they either married or entered the priesthood, in which case we would live alone until we died.

If I was diabetic, then this belief put me at a higher risk of dying decades before I needed to. Being a good Catholic boy felt like a higher risk drug. Gay Catholic celibacy began to feel like coke, while being a naughty gay Catholic boy who lived with someone he loved might be like ecstasy?

These were the questions I didn't ask in my early twenties, when I was feeling hopeful about Church teaching: What if what I want is someone next to me in bed, who will give me insulin when I can't give it to myself, so that I can keep living? What if I want someone that I can do that sort of thing for? What if one of the things we want is a chance at life? And that chance is what the Church tries to deprive us of?

After Christmas, the seriousness of those questions really set in.

Then I got angry. I thought about the value of gay life in so much of the Church. It brought up memories and past anger that I had buried deep. All this bubbled up to the surface.

Shooter

Years before, a now-ex was working in a Catholic elementary school. We kept our relationship a secret in many circles. He was not publicly "out", because awareness of his sexuality or our relationship could result in his getting fired. He had already been pushed out of a past dream job by Catholic students who had gossiped to his boss about our relationship. But, even with all that, he loved his teaching job. And he loved his students.

I loved all that for him. Until I didn't.

One day, the elementary school went into lockdown. A shooter had been identified nearby. He pulled his students into a closet and shut the door behind him. The active shooter alarm went off in the school. He heard someone entering the classroom and put his body against the door, hoping that he could shield the kids if the gunman tried to shoot through it.

But it was a false alarm. Crying kids were led out of that closet. He called me. We talked through it.

I listened to him. I didn't share my feelings at the time. I can't describe the fury within me.

After we hung up, I thought to myself, "This guy used his body to take bullets for these children, but if they knew he was gay and about our relationship, this Church would say he doesn't deserve this job. That is so fucked up. THEY don't deserve him."

That experience changed something in me. I felt so viscerally angry, not simply at the injustice of our situation, but at the appalling indignity of it. I feel that fury in my body now, as I'm typing this. Those institutions don't deserve us. But we still show up there, for the kids. So many queer educators in Catholic schools would die for their students, even as they know that many of those students' parents would have them fired if the way they lived and loved became known.

I used to feel so grateful for love from the Church. I was Carrie Coon in the third season of White Lotus. Over the course of the season, Coon's character Laurie is visiting a resort in Thailand with two friends, and resentments and frustrations bubble up over the course of their stay. Laurie complains about the vanity of one friend, and about the conservative clean life of the other.

In the finale episode, Laurie begins a monologue where she expresses her deep disatisfaction with her own life, and viewers expect she will finally lash out at her friends. But her monologue takes a different turn. She says:

“I just feel like my expectations were too high or I just feel like as you get older, you have to justify your life and your choices. And when I’m with you guys, it’s just so transparent what my choices were and my mistakes. I have no belief system. Well, I mean, I’ve had a lot of them. I mean, work was my religion for forever, but I definitely lost my belief there. And then I tried love and that was just a painful religion just made everything worse. And then even for me, just like being a mother, that didn’t save me either. But I had this epiphany today: I don’t need religion or God to give my life meaning, because time gives it meaning. We started this life together. I mean, we’re going through it apart, but we’re still together. And I look at you guys and it feels meaningful and I can’t explain it, but even when we’re just sitting around the pool talking about whatever and name shit, it still feels very fucking deep. I am glad you have a beautiful face and I’m glad that you have a beautiful life. I am just happy to be at the table.”

Laurie's monologue received rave reviews for its raw power and the ways in which it finds positive meaning in a web of friendship tinged frequently with toxicity. I found the speech compelling. It reminded me of the ways in which I felt intense gratitude when I would find acceptance from other Catholics, how in the past I felt so lucky that people would be friends with me.

Over time I came to a realization similar to Laurie's. I discovered I had a deep dissatisfaction with myself, approaching even a resentment towards my own internal life. As I began to work through that resentment in friendship and therapy and love, I departed from Laurie. I ultimately rejected Laurie's realization when it came to myself. I shouldn't feel lucky just to have a seat at the table. I should find flourishing. I should be seated at tables where we can all bask in the beauty of each other's lives, where our happiness isn't just dependent on having some connection to others' happiness.

All these experience have pushed me to evolve how I view myself, being gay, sex, the Church, and much more. When I think of the Church, I ask myself, “Why should we let strangers in this institution tell us how to live our lives, when we are already giving them more than they deserve from us?”

AIDS

I laugh when I tell the story of coming out to my parents. It was nearly a decade before the false alarm with the shooter. It was late at night after my last year of college. I stood in the doorway of my parent’s bedroom while they sat up in bed and listened. My mother was warm and gentle. She said that she loved me unconditionally. She asked what being gay meant for my Catholic faith, and I shared my hope that I would continue to try to live a full Catholic life.

My father was also warm. He expressed his unconditional love. He wanted to be supportive. But his response was also as if someone had given him a list of things not to say, and he just read down the list. Things like, "I've always wanted grandchildren" and, "Maybe it's just a phase," and, "If you're open about this, it could affect how people treat you."

I can see so clearly that my dad said these things because he loved me, because he wanted me to live a full life, because he wanted to protect me. He just didn’t know any better. Which is why I laugh when I tell this story. He meant well. And he's learned and grown and changed as I've learned and grown and changed.

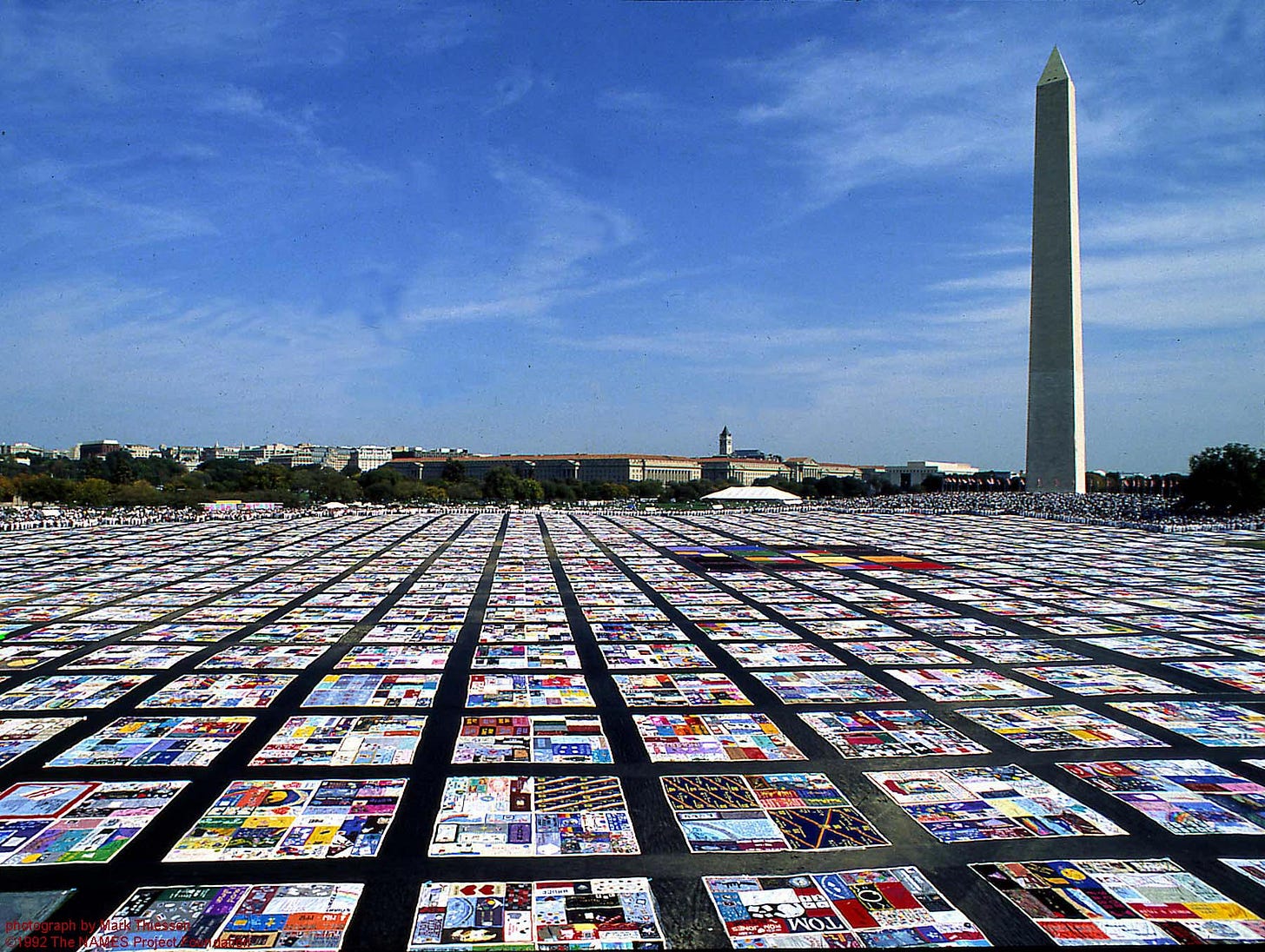

But when I think about why he didn't know a better response, I think about what had happened to his gay friends. After I read Michael O'Loughlin's Hidden Mercy: AIDS, Catholics, and the Untold Stories of Compassion in the Face of Fear, I asked my parents what the AIDS crisis meant to them. They shared the name of a gay friend from medical school who had died of AIDS. The AIDS epidemic took so many in the gay community, all these people who could have taught my parents how to love and support a gay child. Because of HIV, their support system in raising a gay child didn’t exist. It had died.

I think about one of the first people I came out to, a Catholic priest at my college. He was gentle and compassionate. I remember him telling me, "Don't get sick. Do you understand what I mean?" I was too young and naive to really understand what he meant. But now I do. He, like my parents, associated being gay with death. So many of their gay friends had died. The AIDS crisis was part of gay cultural identity for their generation. Had I grown up in their generation, I could have faced a 50% chance of contracting HIV. Today, medical advancements are so effective that individuals with HIV can reduce the possibility of spreading it to sexual partners down to 0.3%. As someone who does not have HIV, I can also take medication to reduce my chances of contracting HIV from sex by 99%.

Funding

In 1994, AIDS was the leading cause of death for Americans aged 25 to 44 years. AIDS had been ravaging gay communities over the prior decade, and Americans avoided addressing it because it had primarily spread in gay communities. But diseases like AIDS will only get worse if we ignore them. The first federal funding for AIDS began in 1986, and it led to a wave of advancements that have protected human lives like mine. Although 1.2 million people are living with HIV in the United States, infection rates are decreasing. The 12% decline in infections from 2018 to 2022 is attributed to education, testing, and medication supported by federal, state, and other funding.

And the United States has been a global leader in combating the spread of HIV and AIDS worldwide. In 2003, President George W. Bush launched the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Calling for "compassionate conservatism," President Bush and his wife Laura Bush wanted to support Africa and other parts of the world in reducing the spread of HIV. The couple had read Alex Haley's Roots, and President Bush decided that stronger support for and collaboration with Africa would be a significant part of his foreign policy. As a result of PEPFAR, it is estimated that more than 26 million lives have been saved through HIV prevention, treatment, care, and support programs in 55 countries. Through US federal funding, it's estimated that 8 million babies were able to avoid being born with HIV.

In 2019, President Trump built on earlier efforts in launching the "Ending the HIV Epidemic Initiative" (EHE), with a goal of 75% HIV reduction in five years and 90% reduction in 10 years. President Biden continued these efforts in his administration. In his State of the Union address in 2019, President Trump sought a budget that he said was a "needed commitment to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years. Together, we will defeat AIDS in America."

But in January 2025, President Trump in partnership with Elon Musk ended longstanding US support by cutting federal funding around the world. This included funding to support the combatting of HIV and AIDS. In the initial couple of weeks after the cuts, it was estimated that 300 babies had been born with HIV who wouldn't have otherwise. It's estimated that these cuts by the Trump administration will lead to a minimum of 60,000 deaths in Sub-Saharan Africa over the next 5 years. Globally, cuts in funding are estimated to result in 4.43-10.75 million additional HIV infections by 2030, including for up to 880,000 children.

Contrary to much public rhetoric, much PEPFAR funding was not intended to be permanent, and did not result in complete dependency on the United States. Currently, South Africa is paying for 83% of its own HIV/AIDS efforts, and PEPFAR had intended to phase out most funding through a carefully planned process over the next 5 years. The sudden funding cuts could result in the reversal of progress that has been made over decades. One epidemiologist with South Africa's Anova Health Institute said that, "Instead of a careful handover, we're being pushed off a cliff." In a rare public comment on politics, Bill Gates announced that he would be giving away his wealth and said of Elon Musk's DOGE cuts, "The picture of the world’s richest man killing the world’s poorest children is not a pretty one."

In his second term, President Trump appears to have abandoned his commitment to combatting HIV and AIDS. A leaked document detailing budget and restructuring plans for HHS under the Trump administration indicates plans to eliminate his own EHE initiative. Hundreds of federal grants for research related to HIV and AIDS were suddenly terminated by the Trump administration over a few weeks, leading to the waste of decades of research and lost opportunities to develop and implement advancements against HIV and AIDS. President Bush had written in his book Turning Point, “I considered America a generous nation with a moral responsibility to do our part to help relieve poverty and despair.” One must now question whether this moral responsibility has been abandoned, whether Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” is now dead.

This Mistr

Many of my friends and I use Mistr for medication to avoid HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). When an individual is not covered by health insurance, the medication PrEP to prevent contracting HIV can cost about $2000 per month. Mistr is an organization that works with a variety of organizations and resources, including public funding, to cover the costs of PrEP where needed.

When I signed up for Mistr, I completed an initial form and was able to set up a virtual visit with a doctor. After the visit, Mistr sent me a kit in the mail to test for HIV and other STIs, which I mailed back. I received my results within days, and then Mistr mailed me PrEP and other anti-STI medication. Mistr's funding meant I didn't need insurance to cover any of its costs. I receive virtual doctor appointments, testing, and medication for free.

A couple of weeks after I received those lab results, I went to see cutie South Minneapolis doctor again. He wanted to retest me, given the possibility of being pre-diabetic. I was scared.

A couple of days after the visit, I received my results. Normal labs. Not pre-diabetic. And STI-free.

I am healthy. I am alive. Through education, testing, and medical advancements, our country gave me what it could not give my parents' friends. It protected my life. And because of this, you are getting this letter.

I think a lot about this one life that I am given to live. I am given more time than my parents' friends. I am given more time than that family friend, my Aunt Julie, who died of diabetes far too early. I am reflecting on legacies, including the legacies of people like President Bush. I made it to thirty-four. I outlived Jesus. Now what?

I have not always wanted to live. The desire to live is something that, at times, I have had to cultivate. That cultivation has come with the gift of gratitude. I am so grateful for this life. And with that gratitude comes anger: anger at the injustice that suggests some lives are worth less than others, anger at the injustice that increases military funding while cutting funding that prevents babies from getting HIV, anger at the injustice that people like my ex would put his body on the line for the kids in a Catholic school that would deem him unworthy as a teacher if they knew his sexuality, and also anger that the Trump administration has cut critical research on diabetes that could help people like my Aunt Julie.

Catholicism has taken much from me. And Catholicism has given me much. In a religion so intimate with blood, where I am supposed to receive body and blood into my body every Sunday, what am I to make of a world so afraid of the blood of LGBTQ+ people? What am I to make of American Christianity, which at times has argued that HIV is God’s righteous punishment for gay people? So much in the Church has supported injustice. And so much in the Church has given me the language, the frameworks, and the passion to fight injustice. Catholicism has given me anger, and it has taught me to use this anger. Thomas Aquinas has written, “Wherefore if one desire revenge to be taken in accordance with the order of reason, the desire of anger is praiseworthy, and is called ‘zealous anger’.” I aspire to the desire of anger that is praiseworthy.

We are worthy. And we cannot wait for others to deem us so. I will not just be happy to have a seat at the table. I will not just be happy to hide in closets with all these secrets, waiting for death. I will not stand silently before a federal administration that does not care whether people like me live or die. We all deserve better.

If you agree with me, I hope you'll reflect deeply about everything I've written here, and about what it would take to create a world where that worth is indisputable.

With Love,

Chris

If you read this and feel inspired to do something, here are some ideas…

Learn more about these and related topics. One book I’d recommend is Hidden Mercy by Michael O’Loughlin (on Catholicism and the AIDS crisis in the United States). Educate yourself on HIV and AIDS and work to combat myths and misconceptions surrounding them.

Help spread awareness surrounding HIV and AIDS and resources to help combat them, such as Mistr.

Donate to and engage with organizations combatting HIV and AIDS, such as the Hill Country Ride for AIDS and The Aliveness Project.

Reach out to your elected officials and tell them that you care about these issues.

My dear child of God. You continue to challenge me and make the world a better place. And I will always love you unconditionally.

Mom