A nurse friend (we’ll call her Emily) recently got into an argument about whether she’s allowed to rant about COVID. Emily had shared a post by a doctor expressing exhaustion and frustration. The post said:

“When we had the surge last year we had no real weapon, but now we have a vaccine (an FDA approved one now). And its getting more and more difficult to have empathy for the incredibly sick covid pts coming in because they are almost always unvaccinated. I've seen so many young, otherwise healthy patients die and they all have a common factor- not getting the vaccine.”

Emily was feeling similarly, working in a hospital running out of beds, full of people who had refused to get vaccinated. Emily has felt overworked and emotionally taxed. One belligerent patient recently told her, “I hope you get COVID and die.”

When Emily shared the post, some responded critically. One woman (we’ll call her Sheila) criticized Emily for sharing it. Sheila said that posts like this just push unvaccinated people away from seeking treatment for COVID because they worry they will be not be cared for by medical professionals. Sheila said that, if she herself felt a lack of compassion in her job, the fault would lie with her, rather than those she was charged with serving. And Sheila said that posts like the one shared by Emily were emotionally manipulative efforts to get people to get the vaccine. Sheila said if there was sufficient evidence for the effectiveness of the vaccine, there would be no need for emotional manipulation. While she said that she supports Emily having her own views on vaccines, she said that Emily should take a different approach with her messaging.

On the one hand, I get where Sheila is coming from. Shame has a way of backfiring. I believe that we should resist using shame tactics to get people to do things, even things that are good for them.

At the same time, both Emily and Dr. Kumar (who wrote that original post) are currently working in one of the most stressful and essential professions in the world, doing work that they did not plan on, and getting no extra pay, benefits, or appreciation. At one point in the pandemic, as we saw the stresses and horrific conditions under which our medical professionals were working, they became our heroes. But after a year and a half, many of us have turned on them, characterizing their pleas for vaccinations and stories of compassion fatigue as “emotional manipulation.”

While I understand where Sheila is coming from, I think she and others would benefit from learning about Ring Theory.

Ring Theory: a change in our response

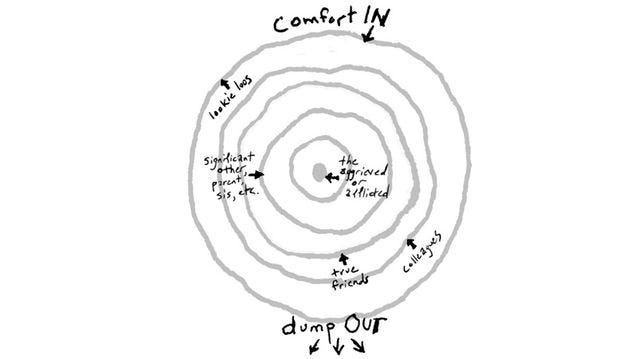

Ring Theory was developed by psychologist Susan Silk and her friend Barry Goldman. It helps identify appropriate responses in a crisis. It’s more a practice than a theory. You’ll need a piece of paper and a pen.

It works like this:

Consider a crisis (here, COVID). Draw a small circle and, in the middle of it, write the name or group of persons at the center of the crisis. (Here, it might be those currently suffering most acutely with the virus. We might write, “COVID patients fighting for their lives.”)

Next, draw a larger ring around the first one. In this ring, write the name(s) of the person/people next closest to the crisis. (It might be “the immediate family of those currently fighting for their lives.” “Medical professionals fighting the virus day-in and day-out” might also be in this circle.)

Continue drawing rings around those, each time adding people who are next closest to the center of the crisis. (In the outermost ring, we might put people like me, those of us who are healthy, have stable jobs, and don’t work in professions actively fighting COVID.)

This diagram now provides a “Kvetching Order.”

The rules established by this diagram are:

Those in inner rings should be given space to dump out their feelings to the outer rings.

Those in the outer rings are responsible for providing comfort and support to the inner rings.

The diagram helps us to understand who is most in need, and to order our responses accordingly. (So those fighting for their lives with COVID can complain about their condition with medical staff, who can complain about their working conditions to the public. And the public is responsible for supporting medical staff, who is responsible for supporting those dying with COVID.)

Support can come in a number of ways, but often the most important, and first effort of, support is just listening. The inner circles need to be heard. And while they are in the throes of the crisis, they need to be heard without criticism or judgment. Critique can come from those in the same circle or in inner circles. But critique from outer circles should occur only at a time when the crisis is not so imminent and the circles become less important, that is, when the crisis stops being so much of a crisis for them.

Why focus on the medical profession?

Some might wonder why healthcare workers get such a central place in the circle. After all, they’re just doing their jobs. And they’re fortunate to have jobs, given the number of layoffs that have occurred over the course of the pandemic.

These responses fail to take into account how healthcare workers have been disproportionately harmed over the last couple of years, and how they will continue to suffer harm even after the pandemic ends. A study released in December reported that three-quarters of healthcare workers were experiencing exhaustion and burnout and feeling consistently overwhelmed. The majority with children said they were afraid for their kids’ health and safety. More than three-quarters were experiencing trouble sleeping and work-related dread. And more than half experienced changes in appetite, compassion fatigue, and heightened fear in their work. Roughly half of healthcare workers, and two-thirds of nurse practitioners, had cried at work over the last year. Healthcare workers have also been at a higher risk of contracting COVID than the general population. They have also been at a higher risk of suffering physical and verbal violence because of their work.

And while healthcare professionals have been expected to do the majority of the work in caring for our communities during the pandemic, they have not received the same care in return. Many have had feelings of disillusionment and abandonment compounded “by political divisions over COVID-19 data and the refusal by many Americans to comply with public health restrictions.”

It’s likely that our medical professionals will experience harm long after the pandemic is over. During the pandemic, nearly one-quarter of all health care workers reported signs of probable post-traumatic stress disorder, and 43% had probable alcohol use disorder, according to a study published in February. And because of the increased stresses experienced during the pandemic, medical professionals are expected to have enduring chronic stress effects for months to years after the pandemic ends. Individuals often become nurses and doctors after dreaming about these professions for much of their lives. They have undergone intense education and training in order to serve the community. But this work has been so grueling over the last year that three out of ten healthcare workers are considering leaving the profession.

The present inversion

So when we consider Ring Theory, what should be the most natural flow of “dump” and comfort has often been inverted over the course of the pandemic. Those in the medical profession have tried to share their emotional struggles and begged the public to take measures to help take the strain of the healthcare system. But rather than being heard, medical professionals often get dumped on in response. Healthcare workers are told that their emotions and first-hand daily accounts have equal validity with the hypotheticals spun by those of us who don’t face COVID every day. We somehow think that our imaginings and anecdotes can be used to judge their daily experiences. And then we expect them to care for us with smiles on their faces.

Ring theory helps us see how distorted this is. It helps us to see that a much more appropriate response from Sheila would be: “I’m so sorry how hard the last year and half has been for you! How can I support you?”

Sheila can still worry that shame-based messaging might result in hesitancy for people to seek care if they fall ill with COVID. That is fair. And Sheila can use her own platform to share messages like, “Some of you have expressed concerns that hospitals won’t care for you if you get COVID and aren’t vaccinated. They will. But medical professionals are getting frustrated when Americans aren’t doing what they can to keep from ending up in the hospital. And that is also fair.”

When it comes to medical professionals like Emily, Ring Theory helps us to understand that our direct responses to them should be characterized by care, comfort, and compassion. When medical professionals share frustration and exhaustion, and beg people to take action because of it, it’s not our place to indirectly accuse them of emotional manipulation. It’s not our place to say that they are causing harm by sharing. The people in an appropriate position to say such things would be those in a more central ring, those fighting for their lives with COVID. And they’re begging people to get vaccinated as well. Imagine if we treated those people like we treat our healthcare workers, accusing them of fear tactics and emotional manipulation.

Anyways, I sent Emily $5 to get herself a coffee. You should, too.

I’m also open to other ways we can support our health care professionals! Feel free to share your ideas in the comments!

Some additional data on COVID, vaccines, and the medical profession:

Hospitalizations:

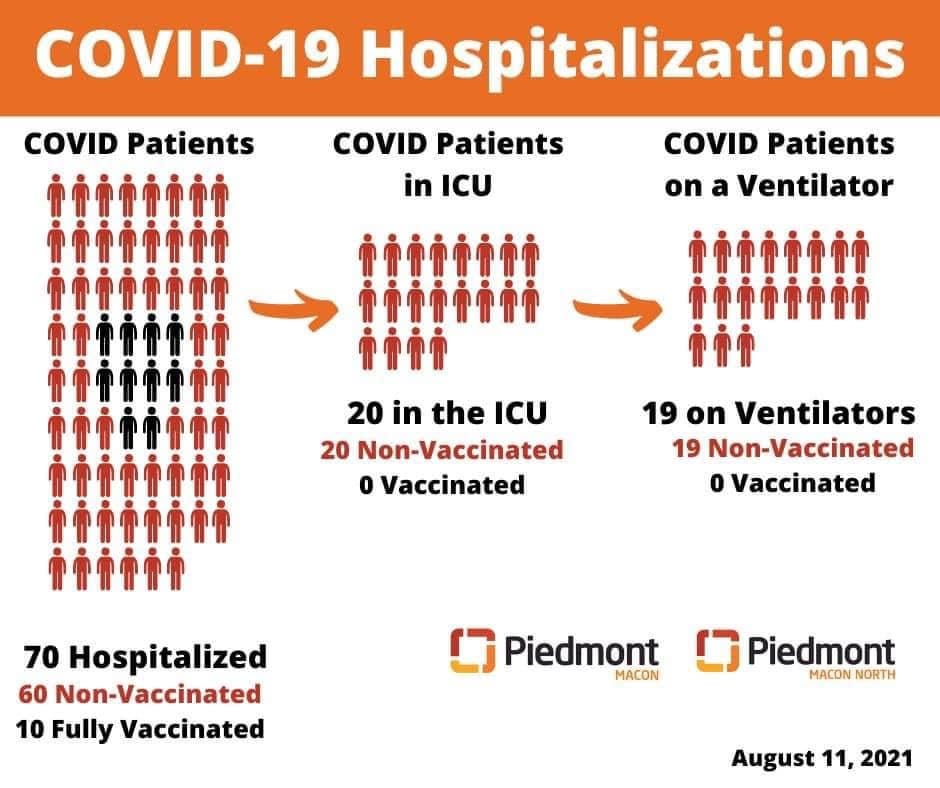

Hospitalizations nationally (as of 8/17): The current 7-day average for August 11–August 17 was 11,521. This is a 14.2% increase from the prior 7-day average (10,088) from August 4–August 10. New admissions of patients with confirmed COVID-19 are currently at their highest levels since the start of the pandemic in Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oregon, and Washington.

San Antonio ran out of ambulances for nearly half an hour on August 12 because of the high number of people needing to be rushed to the hospital with COVID. During that period, no emergency calls were able to get an ambulance response.

Because of COVID surges, states that have run out of ICU beds include Alabama (as of 8/23) and Arkansas (as of 8/25). States that are about to run out include Florida (as of 8/23), Georgia (as of 8/24) Idaho (as of 8/23), Illinois (as of 8/23), Kentucky (as of 8/23), Minnesota (as of 8/24), Mississippi (as of 8/24), Nevada (as of 8/23), Oregon (as of 8/25), Texas (as of 8/24), and Washington (as of 8/25). As of 8/25, three-quarters of beds nationally were full. You can track hospital ICU bed utilization here.

By mid-August, the situation in Texas had become so dire that Governor Abbott had to seek out-of-state medical help.

Vaccine efficacy and dangers:

No vaccine will provide 100% protection from illness. But as of August 24, the CDC reported that the COVID vaccines significantly reduced both spread and serious illness. Unvaccinated persons are almost five times more likely to contract COVID than fully vaccinated persons.

Though COVID rates are on the rise, the New York Times reported on August 10 that in the states with the highest rates of hospitalization, those who are fully vaccinated make up 0.1-5% of those hospitalized. They make up 0.2-6% of those who have died from COVID. In Arizona (which currently has the highest hospitalization rate), chances of hospitalization for unvaccinated persons are 47x higher and chances of death are 73x higher.

A number of hospitals are sharing their numbers. Many are sharing that, while ICU use is increasing, ICU patients are exclusively unvaccinated persons.

Some have raised concerns about “vaccine injury.” VAERS reported that 0.0019% of people who received the COVID vaccine may have died as a result. (Reports of adverse events to VAERS following vaccination, including deaths, do not necessarily mean that a vaccine caused a health problem.) But assuming that every VAERS death reported was due to the vaccine, chances of dying from COVID are still more than 500x higher than chances of dying from COVID vaccines (more than 1000x higher if you’re over the age of 60). In addition, refusing vaccination increases chances you will give COVID to someone else and harm them, while vaccination decreases these chances.

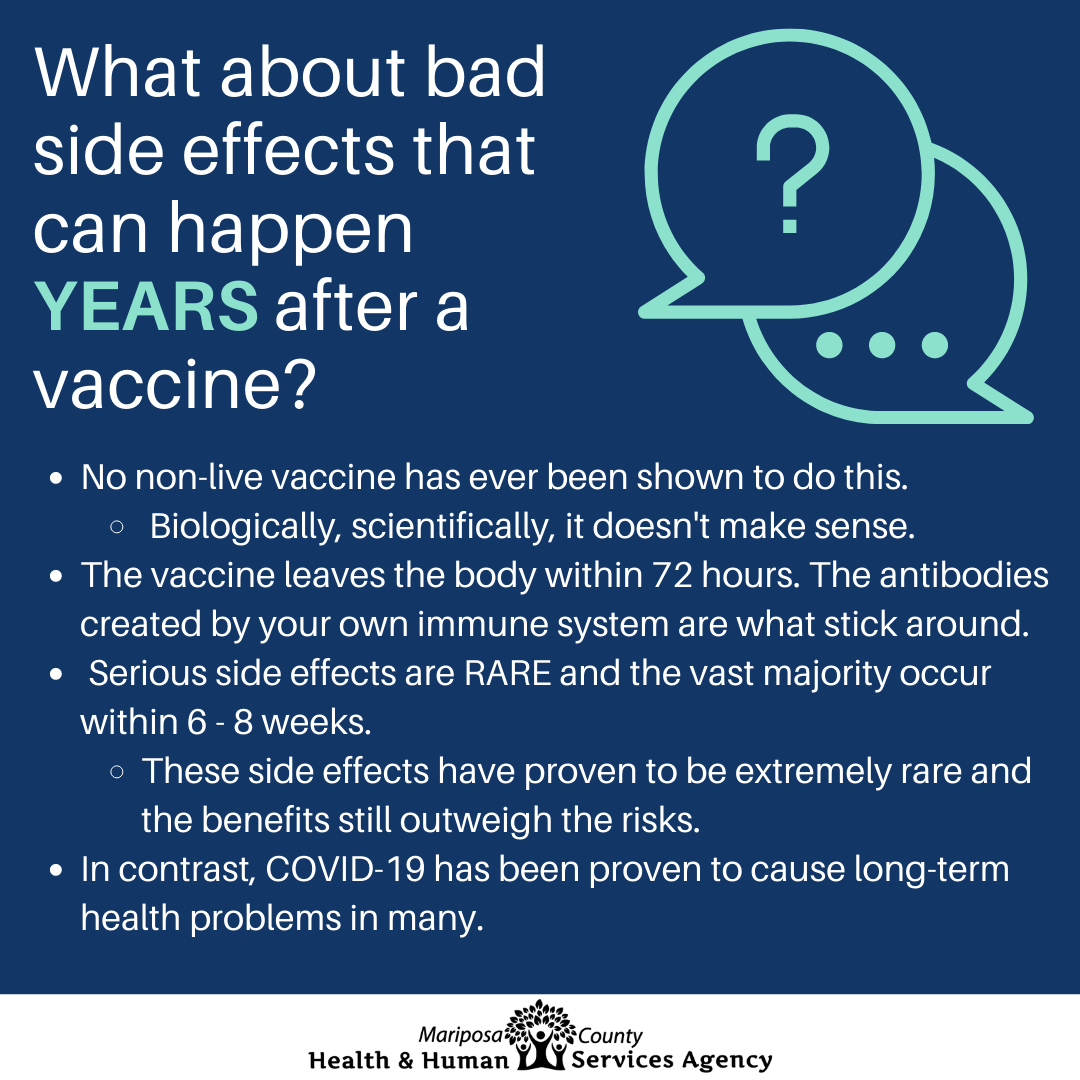

Some are concerned about long-term effects of vaccines. Mariposa County Public Health has provided an infografic explaining that no non-live vaccine has ever been found to cause side effects years later. The vaccine leaves the body after 72 hours and leave behind only the antibodies. And serious side effects are rare and mostly occur in the first 6-8 weeks. All vaccines in use have been tested for longer than this.

The state of the medical profession:

A study released in December found that among healthcare workers: 93% were experiencing stress, 86% reported experiencing anxiety, 77% reported frustration, 76% reported exhaustion and burnout, and 75% said they were overwhelmed. More than three quarters of healthcare workers with children said they were worried about exposing their child to COVID-19, nearly half were worried about exposing their spouse or partner, and 47% were worried that they would expose their older adult family members. Emotional exhaustion was the most common answer for changes in how healthcare workers were feeling over the previous three months (82%), followed by trouble with sleep (70%), physical exhaustion (68%) and work-related dread (63%). Over half selected changes in appetite (57%), physical symptoms like headache or stomach ache (56%), questioning career path (55%), compassion fatigue (52%) and heightened awareness or attention to being exposed (52%). Nurses reported having a higher exposure to the coronavirus (41%) and they were more likely to feel too tired (67%) compared to other healthcare workers (63%). Of all healthcare professionals surveyed, 49% have cried at work in the past year -- and 67% of all nurse practitioners admitted to doing the same.

Dangers associated with bad information:

Americans taking bad advice: After Ivermectin was spread as a possible medication for COVID, against the advice of the FDA, the Mississippi Department of Health reported that more than 70% of the state’s recent poison control calls had been related to ingestion of livestock or animal formulations of ivermectin purchased at livestock supply centers.

Enjoy this piece? To get more essays delivered to your inbox, as well as my bi-weekly newsletter, subscribe now! Through the month of September, all profits from paid subscribers will be donated to support Afghan individuals and families.